![]()

1

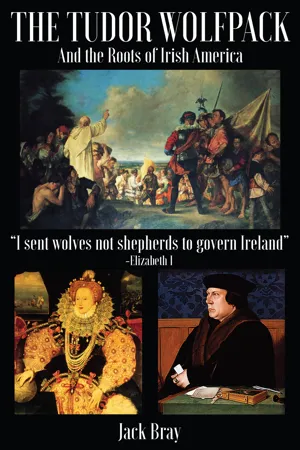

Autumn Turns to Winter

I find that I sent wolves not shepherds to govern Ireland, for they have left me nothing but ashes and carcasses to reign over.3

—Elizabeth I

The O’Neill awaited news from Spain, and this time he was hopeful. The autumn of 1601 was beginning to show its colors in the trees of Ulster as if to decorate the scene for the arrival of welcome news. Things had gone wrong two years ago when Spain tried to send him troops to support his rebellion. Storms drove the Spaniards away; but now the sea was cooperating. He was hoping for a message that reinforcements had landed. O’Neill knew the message would be brought by some young clansman scampering up the hill to the O’Neill Castle at Dungannon, breathless, to bring exciting news to Hugh O’Neill, (Aodh Mór O’Neill), former Earl of Tyrone, now Ireland’s rebel chieftain.

The Spanish army tossing about at sea in 33 ships on their way to Ireland was a small force of about 4,000, but enough reinforcements to make the Irish chieftains confident of victory. For O’Neill, this could mean the difference between life or death. The Spaniards’ arrival could save him from the grisly fate of a rebel—a death that might start with his arms and legs being broken, then dragged out for many days. England had decided upon “the extirpation of the native and so-called Old English population, and the resettlement of the cleared countryside and towns by British immigrants.”4 By O’Neill’s day in the sun it was abundantly clear to the Irish chieftains that Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth I had come to view the native Irish as savage and disloyal and had despaired of peaceful Anglicization. Exasperated, she was now bent on ridding Ireland of the disloyal Irish.5 “[T]he sword of extirpation hangeth” over the Irish,6 O’Neill wrote as he tried to encourage other potential rebels.7 He was now confident the English sword would hang above them no longer if Spanish troops landed in Ireland. The native Irish could begin to renew their society which Tudor England had been busily erasing from history.

Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone

The most recent Spanish emissary, Ensign Pedro de Sandoval, had come to Sligo in late Summer 1601 and met with The O’Donnell, the chieftain Red Hugh O’Donnell (Aodh Ruadh O’Domhnaill), to coordinate the plans for the arrival of the Spaniards. He told O’Donnell that troops were ready in Spain and would soon sail for Ireland. They were fewer than the chieftains hoped for, but still a strong force to bolster the clans’ forces. The chieftains, however, alerted Sandoval that Queen Elizabeth had sent a very large English army into Ireland under her new Deputy, Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy, and much of his army was currently massed in the south. They warned Sandoval that such a small Spanish force should avoid the south at all cost. Sandoval agreed and hurried back to Spain to warn that the armada must sail farther north to avoid the English troop concentration and instead land where it would be welcomed by northern Irish clans, and then together prepare to fight the English in Ulster.

That was now many weeks ago. Sandoval arrived back in Spain on October 1 where he was met with disheartening news—the Spanish troop ships had already sailed, and they had selected Kinsale on the south coast as their landing site. They had been at sea for several weeks and there was no chance to reach them.

The Spanish troops did land at Kinsale the very next day, October 2. And when the breathless clansman brought that news to O’Neill, his elation was gone in an instant. The Spaniards were already trapped by English troops. Mountjoy’s army had set up siege camps on the four hills outside the walls of Kinsale while the rattled Spaniards huddled inside. The Spanish had turned themselves from welcome reinforcements into a demanding distraction.

O’Neill hoped that the Spanish might escape Kinsale by sea and sail north, but the Spanish leader smuggled a message out to O’Donnell that their ships had all left and they had no way to escape. The Spaniards urged the northern chieftains to march to Kinsale and rescue them. The clans would have no choice but to leave the safety of their lair in Ulster, march in mid-winter the length of Ireland, and they would likely have to fight the decisive battle that would decide the fate of the Irish on open ground against English troops well trained for cavalry charges and lines of musket fire, free from the confines of the Ulster woods favored by the clans.

![]()

2

Collapse of the British Lordship

Hibernia Hibernescit (Ireland makes all things Irish)8

—An ancient observation

By this time, the Ulster clans had been at war against the Crown for 9 long years. How had the centuries-old relationship of England and Ireland come to this? Long ago the Irish had become used to the English lordship. They had accepted the English monarch as the overlord of Ireland back in 1175 when the Plantagenet, Henry II, accepted the submission of many of the Irish kings. The lordship had been reaffirmed in the mid-16th century and had not even then seemed a threat to the Irish people. Henry VIII had obtained the agreement of most of Ireland to surrender their lands, but he immediately regranted those lands to the chieftains and they accepted him as their distant overlord. In 1541, Henry VIII had also proclaimed himself their King, and the Irish accepted that as well. What had happened between 1541 and 1601 that had so badly derailed this time-honored relationship? There had been only scant rebellion9 in the previous 400 years10 since the English first arrived. Most disturbances had consisted of raids by chieftains on the Old English, the descendants of the Normans, who had settled in the Pale. Those raids were more like cattle rustling than rebellion.11 Most Irish had given little thought to rebellion against their English overlord. Yet in the middle of the 16th century rebellion had begun, and by 1601 some in Europe had begun to wonder whether England would prevail.

Most puzzling to Europeans as well as many London courtiers was that the rebellion was led by a lifelong ally of the English, the Earl of Tyrone, Hugh O’Neill. He and the other Ulster chieftains were well aware that previous stories of a swashbuckling rebel challenging a powerful king or queen that began as rousing tales often ended with the rebel’s head on a pike. They knew also that one man’s rebellion is another’s treason. Why did O’Neill risk death for himself, his family, and attainder for his clan? Why had he turned against a Queen he had praised for her kindness to him, the Queen for whom he had such affection that, later, at her death, he burst into tears.

Something new and very unsettling had found its way into England’s Irish policy during the 16th century. England was no longer merely punishing the Irish countryside with coercion measures used to pacify unruly clans; that was certainly nothing new. English officials had been using coercion to pacify the “Wild Irish” for centuries. Efforts to Anglicize some of them had also been around a long time and, in some areas of the south, the east and the west those efforts had achieved considerable success. The extensive Ormond earldom in Kilkenny had become loyal to the Crown; it had “gone English.” The earl of Clanrickard in the far west in Galway had gone so English he was called “The Sassanach” (Englishman). The Pale in the east, and Dublin, had long been loyal. So were other walled cities. While other areas outside The Pale and the cities remained Irish, their political temperature rarely rose to the raging fever of rebellion even through the early 16th century.

Earlier rebellions had erupted over distinct localized provocations in regional lordships—in Kildare in Leinster under the Earl of Kildare in 1487 and under the Earl of Offaly in 1534, in Tyrone under Shane O’Neill in Ulster in 1567, in Desmond Munster under James FitzMaurice in 1569 and under the Earl of Desmond in 1579, in Leinster under Lord Baltinglass in 1580, and in Connaught under the Burkes in 1572, 1576 and 1586. Those rebellions had not spread throughout Ireland; they had been regional—disorganized, even chaotic, and all had been crushed. This was different.

Map of 16th Century Irish Lordships, circa 1534.

The 16th century Irish chieftains had not simply grown weary of foreign rule and rebelled to achieve independence. They had tolerated rule by a foreign monarch, and they were used to foreign settlers—the Danes who invaded in the 9th century and the Normans who invaded in the 12th century. By the Tudor era the Normans or Old English were a wealthy Irish peerage. Some of that nobility had bonded very well with the native Irish and all had become comfortable with the fact that their overlord was the English monarch. And they were used to accepting the notion that the King could choose his subjects’ religion.141 This was the reality of 16th century Ireland.

Central to that reality was that, to the 16th century Irish, there was no Ireland.12 Centuries earlier there had been a High King, but the concept of a modern Irish nation had not yet been born. As Professor Edmund Curtis described 16th century Connaught: “There was indeed as yet no Irish nation and the aims and local pride of the Connaught lords were a whole world removed from those of burgesses and landlords in the Pale.”

Outside of Dublin and a few walled towns, the Irish were provincial small villagers. Many of them were allies only of those in their small settlements. Few, if any, felt loyalty to some incomprehensible all-island nation or to distant peninsulas or towns with which they were totally unconnected. Most Irish had experienced only vicious clashes with other villages, and those clashes had made them enemies, not friendly neighbors.

Tudor Courtiers Discovered the Riches of Office in Ireland

What had changed in the 16th century was that Tudor courtiers had awakened to the fact that local governance by the Irish kept the riches of Ireland out of the hands of the Crown and out of their own pockets. England under Henry VIII at times had severe financial worries. Few of the Tudor era courtiers had any wealth and many were in debt. None had much hope of being rewarded with rich lands in England. Ireland was very tempting to Lord Chancellor Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, to Thomas Cromwell, and other Tudor officials.

A new era of political corruption came about in England and Ireland and it became possible for English courtiers to grow rich off the Irish, but the sources of wealth, land and cattle, were already owned by native Irish and Anglo Irish and, therefore, had to be confiscated from them.13 The weapons the courtiers needed to confiscate Ireland’s lands were a strong royal army, control of the Dublin Council and parliament and the tribunals that would decide disputes. Such control enabled the Tudor courtiers to confiscate vast Irish lands, to take some by murder, some by fraudulent claims, and some by escheatment.14 Martial law executions allowed them to take specially targeted lands; by securing the attainder of a wealthy Irish lord, they could confiscate his entire lordship. And if an earl could be toppled, his entire earldom, a significant fraction of Ireland, could be confiscated in one fell swoop.15

The Tudor courtiers of the 16th century set out to use all of these ploys. Fines were levied arbitrarily. False title claims to valuable Irish estates were presented to compliant and complicit Tudor officials. Tudor martial law soldiers they named seneschals were permitted to execute arbitrarily any Irish they deemed guilty of treason, and to confiscate their property. The local death rate in an Irish lordship rose dramatically when the seneschal and his goon squad came calling.

The Tudor courtiers who came to 1...