- one -

Our Complicated Bible

Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.

Antoine de Saint Exupéry

What is the Bible?

There are the usual answers: The Bible is the Word of God. The Bible is God’s inspired truth. The Bible is divine revelation. Or, the Bible is an ancient, mythological and unscientific book. Others jump to more descriptive answers—adjectives more than answers, really. The Bible is perfect, wonderful, insightful, helpful, encouraging and so on. Alternatively, for some it is incomprehensible, irrelevant, bloody, damaging or worse. But we haven’t really answered the question: What is the Bible? When I open the book or turn on the screen, what is it precisely that I’m encountering?

Many people claim the Bible as the foundation of their life. Churches around the world and through the ages have pledged their commitment and faithfulness to it. It is therefore somewhat astonishing that we rarely stop to answer this question: What is it, exactly? I suspect that we pick up signals based on how we see the Bible being used and deduce from them what the Bible actually is. But our practices send confusing and conflicted messages. Most people simply haven’t worked out clearly and consistently what they think the Bible is. And I would venture that most churches don’t expressly address this question either; more likely they just go about their business, using the Bible in various ways. Again, I say, this is quite remarkable given the vital importance we claim for the Bible. You’d think we’d make sure those within our spiritual communities know what the Bible is in the interest of helping them interact with it appropriately.

I do know a man who addressed this question head-on in an adult Sunday School class. The class was an introduction to the Bible and at the end the following question was included in the review test:

Which of the following is the Bible most like: (A) Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, (B) The Reader’s Digest Guide to Home Repairs, or (C) The Collected Papers of the American Antislavery Society?

What was this teacher looking for? He summarized it this way: “The correct answer is C, although we most often use the Bible like A and expect it to be like B.” Part of his intention in the class was to help the students realize that “the Bible is a series of occasional pieces of various genres that traces the development of a transformational movement.”1 To this we will return—when we reach the climax of our journey to the center of the Bible, we will need a good, summarizing description like this one.

But our task in this chapter is more limited. We need a first-level answer to the question. Let’s begin by simply trying to see the Bible clearly. After all, we identify many things based on how they present themselves to us. So, what does the Bible look like it is? How is it presented?

A Short History of the Complexification of the Bible

We’ve never been able to leave the Bible alone. Ancient manuscript collections of the Bible reveal a fairly universal compulsion to tamper with the sacred text. From very early on, Christian scribes did more than record bare words. They began to interact with the sacred writings, minimally at first. Things begin to happen in, around and under the Bible’s own words.

While the wider cultural aesthetic preference was for scriptio continua (no spaces between words and no punctuation), early Scripture manuscripts began introducing new features. Many of these seem to be related to providing “helps” for the public reading of the Bible. We should remember that most people did not see these manuscripts, but rather heard them being read. Writing material was scarce and expensive and not many people could read and write. So the first additions to the Bible’s pages were there for those who read them to others. Breathing marks, paragraph or other sense unit markings, visual cues used to mark the beginnings of new words, and page numbering all appear.

There were also special abbreviated ways of presenting the divine names. Monogram-like combinations of Greek letters superimposed on each other debuted as with the tau-rho and later chi-rho pairs that functioned as shorthand ways of referring to Christ. Other symbols were creatively scripted in among the words. Visually pure Bible texts are pretty hard to come by.2

What began as very circumspect intervention, however, grew into something more. We moved from textual glosses, marks, symbols and chapter divisions to full-blown commentary and ornate artwork. All of this shows up not only in the margins but also in the spaces between lines and wrapped around the holy words. The temptation to comment directly on the biblical page has been indulged by copyists from the start. It’s inevitable—and a healthy sign anyway—that a text as significant as the Bible’s provokes strong responses and interactions. However, dangers lurk here.

First, it’s essential that the boundaries of what is sacred and what is not remain clear. For receivers of the text, the aura of authority can easily start to float over our own commentary. Second, even when the boundaries are clear, the additions can become bloated and overwhelm the Bible text in appearance and thus perceived importance. Third, commentary in particular can become a kind of overbearing boss, fencing in the text and restricting the interpretive possibilities. It becomes very easy to squeeze the Bible into a mold, reversing roles with a text that is seeking to reshape us around its story.

Marking divisions in the text is perhaps the key intervention made through the Bible’s history. These divisions could include paragraphs, marked sections for readings or the topical gospel canons produced by the fourth-century church historian Eusebius. (Paragraph markings in the First Testament, inserted to aid in the weekly synagogue readings, predate even the writing of the New Testament.3) Various chapter systems of the New Testament were made, including one that broke Matthew into sixty-eight sections, Mark into forty-eight, Luke into eighty-three and so on. Chapters were organizing principles, developed to structure liturgical readings or to help speed the finding of passages and topics within the Bible. Their guiding principle tended to be breaking up the text into sections of roughly equal length rather than attentively revealing the natural literary sections of the Bible.

We tend to think of our ever-present modern Bible companions—chapter and verse numbers—as belonging inexorably together. But they actually have separate histories. The chapter system we know today was developed around the year 1200 by the English church leader Stephen Langton. But this system wasn’t immediately standardized. For example, the famous printed Bibles of Johannes Gutenberg, beginning in the 1450s, didn’t include it. Eventually, however, Langton’s chapter divisions would be married to verse markings, and the new arrangement would become a dynasty. That’s a bit of a story, and we’ll get to it shortly.

The story of Bible verses brings us to the real birth of the modern Bible. We can see this momentous emergence by focusing on the few short years from 1525 to 1557. Once the new cultural form took shape, it spread remarkably quickly and soon became the assumed, standard presentation of the Bible. The reasons for this are historically intriguing, revealing of what a lot of folks apparently wanted the Bible to be.

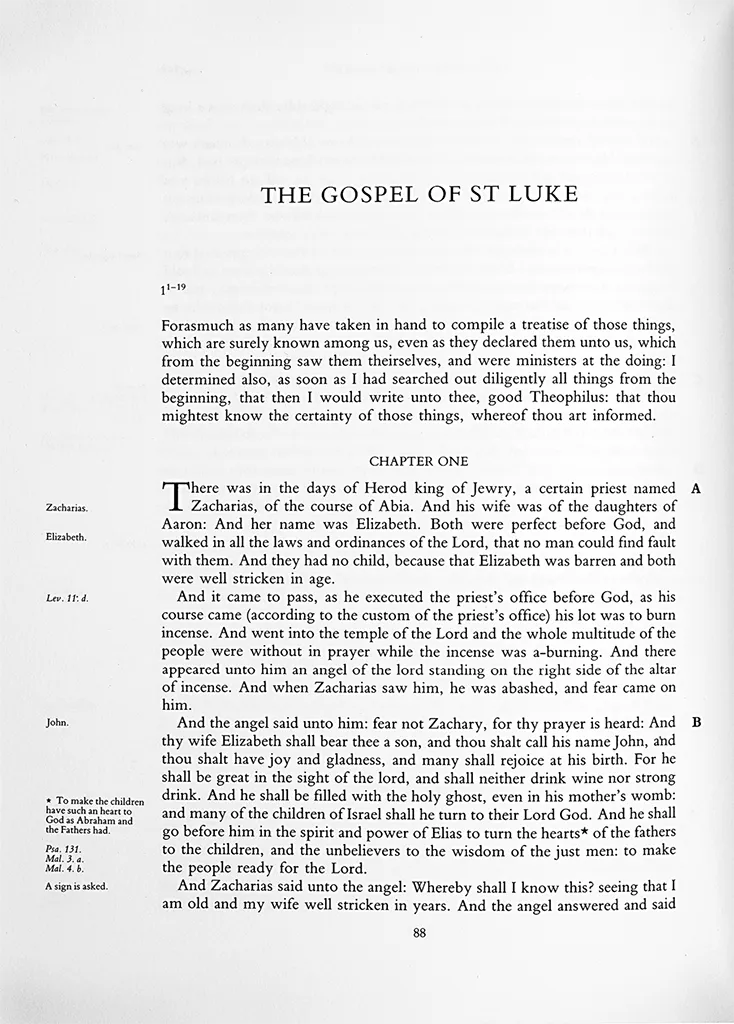

This particular chapter of the story we are concerned with has a pleasant enough beginning. William Tyndale’s first New Testament in 1525 was a readable, coherent presentation: a single-column setting fairly attuned to literary form. For example, in Luke’s Gospel lists and songs are presented in unique forms, appropriate to embedded subgenres. There are no intrusions to the text save for chapter headings. Overall it is an accessible work that invites big readings.

But the changes began quickly. In the 1530s extrabiblical material was increasingly poking into the sacred text itself (not just the margins) and two-column settings became the norm. The decisive turn for the modernist Bible, however, was the introduction of numbered verse divisions. By the sixteenth century the chapter numbers that we know today had been in place for three hundred years. But Reformation-era Bible dueling required a greater level of fine-tuning. The first attempt at inserting numbered verse markings was made by an Italian scholar, Santi Pagnini, who in 1528 versified a Latin New Testament. But as with those earlier alternate chapter divisions, Pagnini’s numbering system didn’t take hold.

Figure 1.1. Tyndale’s New Testament

It didn’t take long for the experiment to be tried again. Similar new cultural expressions often occur independently yet in close historical proximity. In this case, something seems to have been insisting on coming to expression in the Bible realm, and the turn to modernism was its fullness of time. Close to the heart of modernity is the impulse to segment, in the belief that the path to understanding comes from the exhaustive examination of the constituent pieces of a thing. Sure enough, Robert Estienne, a French printer and classical scholar, gave numbered verse divisions another shot in 1551. What was Estienne’s motivation? He wanted to produce a Bible concordance, a tool that would change decisively the answer to the question, what are we supposed to do with the Bible? Estienne introduced his numbered verses to a Greek New Testament, and this time the system caught on. These are the verse numbers we see reflected in most Bibles today. All that was left was to number the older verse markings that already divided the First Testament. Everything was in place for a fully segmented, modernistic Bible. Tyndale’s beauty had been escorted to the edge of a cliff.

Just a few short years later in 1557, an edition of the Geneva New Testament turned each verse into a paragraph of its own. In 1560 the Geneva Bible would repeat and enshrine the error. As for Tyndale’s clean and readable text? Over she goes. In truth, it was a kind of death, a demolishing of the natural form of the Bible. Of course, literary words would continue to be translated, but words alone do not literature make. King James I of England, unhappy with the strongly Calvinistic notes in the Geneva Bible, would commission a new English translation a generation later. The King James Bible was a literary masterpiece as far as its language was concerned, but it continued the destructive device of indenting and thus isolating each newly-numbered fragment. And it became the new standard for Bible printing. It was the death knell for a certain kind of Bible, a Bible that presented something closer to what the Scriptures inherently were. In this new form an essential part of the literature had withered, expired and disappeared, namely, the form.

It is critical to note here that Estienne’s intention was to produce a reference tool (a concordance for a Greek New Testament), but the Geneva Bible took this specialized form intended for a specialized use and transferred it to a Bible for general readers of the English text. The new form became standard, and its visual message altered how readers perceived and understood the very nature of the Bible.

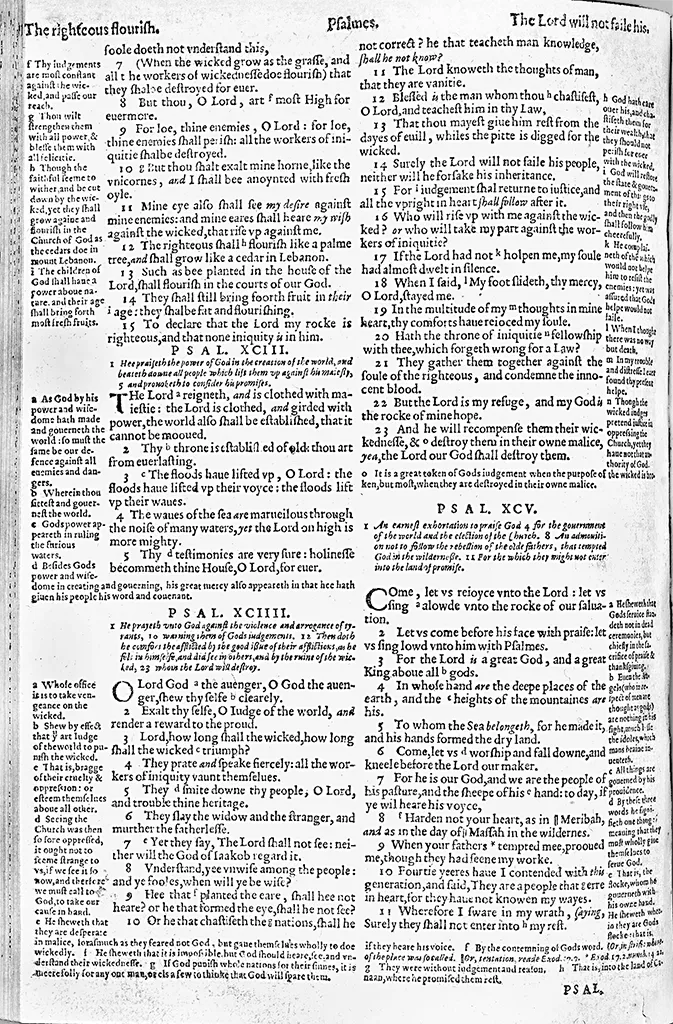

Figure 1.2. A page from the Psalms in the Geneva Bible

At stake here is a key feature of any reader’s communication pact with any piece of writing: the recognition of an author’s chosen literary type and a subsequent agreement to follow the rules of that choice. Once the Bible is visually fragmented and made uniform, where then is the letter, the poem, the oracle, the story? They are gone with the new modernist wind and replaced by bits and pieces, all numbingly the same, a uniform list bound by two columns on the printed page. The new form actively works at undoing the author’s literary intentions as well as the reader’s understanding of their corresponding obligation. As the reader takes in the numbered list going down the page, the message is clear: these propositions are meant to be read and understood independently as separate statements of spiritual truth. And the Bible, therefore, is the collection of these true, perfect, divine spiritual statements.

This revolution was actually twofold. The new modern reference imprint that was placed on top of the Bible text simultaneously masked the original, natural units of the text while also imposing a new structure of numbered, fragmented micro-units. It was a double loss: the Bible’s native form was lost as a foreign one was forced in. This colonization of the Bible text would decisively change the course of the Bible for the next five centuries.

This wind blew in quickly, and the change it brought was momentous indeed. From now on the versified Bible became what almost everyone thought of simply as the Bible. The Bible had gone from being a collection of books—a rich variety of genres, each fulfilling its specified task in the developing overall narrative—to a list of singled-out statements. It was the form that morphed, but this changed what the Bible was for people. As Bible historian David Norton says of this crucial period, “The reader is being directed to texts rather than to the text.”4 The early modern period thus proved to be a crucial one for the Bible. As we will see, there was a direct link between the new form of the text and new Bible practices.

What does the Bible look like now? How is it presented? What does the format of the Bible tell us it is? Before anyone even says a word, the modern complexification of the Bible has staked out its preemptive position on the issue and has already shown us what the Bible is. And given this predetermined answer in the format itself, it should come as no surprise at all what people will then do with this Bible.

Bamboozled by Biblioclutter

In 1707, one hundred and fifty years after the appearance of the Geneva New Testament, philosopher John Locke would write that the Scriptures “are so chop’d and minc’d, and as they are now Printed, stand so broken and divided, that . . . the Common People take the Verses usually for distinct Aphorisms,” and “even Men of more advanc’d Knowledge in reading them, lose very much of the strength and force of the Coherence, and the Light that depends on it.”5

Chop’d and minc’d, the modern Bible has bad complexity. This is not the kind of complexity that science speaks of these days, those intricate patterns of nature—waves, leaves, coastlines—formed by the simplest of small patterns iterated and reiterated over time and space. That kind of complexity is pleasing to us and fitting to the nature of things. But the Bible’s newfound complexity is artificial, intrusive and ultimately misleading as to the tru...