1

A Short History of the Canadian Constitution

What is the Constitution of Canada?

As a country, Canada was born on July 1, 1867. As an organized society, Canada existed for thousands of years, since the first Indigenous people lived together on this land. Every society has a “constitution” in the sense of the basic rules about how that society will be governed. For Indigenous peoples, their constitutions were largely unwritten.

Most countries have a single document that is identifiable as “the Constitution.” That is certainly the case for our American neighbours, but also for France, Germany, and South Africa. Canada is one of a small group of countries whose constitution consists of a group of documents. Section 52 of the Constitution Act, 1982 states that the Constitution of Canada “includes” what we now call the Constitution Act, 1867 and the Constitution Act, 1982 as well as a list of 24 other laws or orders-in-council issued by the British government or by the Canadian government. The Supreme Court of Canada has said that this list is not exhaustive and other laws or orders could also form part of the Constitution of Canada.

There are also unwritten parts of our Constitution. These include constitutional conventions, which are long-held political rules about how powers under the Constitution are exercised. For instance, there is an unwritten rule that the prime minister should have a seat in the House of Commons, even though there is nothing written in the Constitution stating this. There are also unwritten constitutional principles, like the rule of law, democracy, federalism, judicial independence, and the protection of minorities, that are guiding principles that help explain how our system of government works, but they aren’t actually found in the text of the Constitution.

Generally speaking, however, when people refer to the Canadian Constitution, most of the time they are referring to the contents of the Constitution Act, 1867 and the Constitution Act, 1982 — this book contains only these documents.[1] But how did the Canadian Constitution come to be?

Confederation

In September 1864, representatives from Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island met in Charlottetown, P.E.I., to discuss the idea of a federation of these provinces. A federation is a political structure in which power is shared between a central government and local governments, in this case the provinces. Indigenous peoples were completely ignored and excluded from this process, despite a 1763 Royal Proclamation that made important promises to Indigenous peoples.

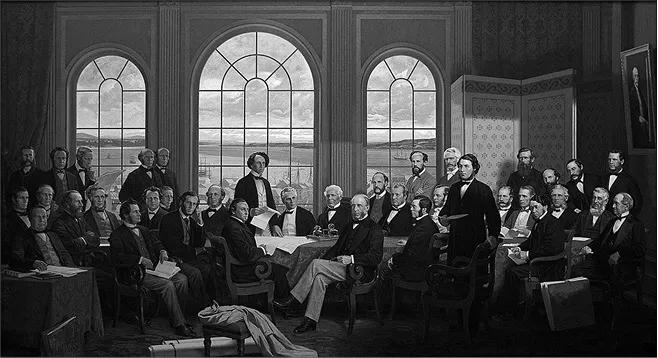

The delegates — who came to be known as the Fathers of Confederation — agreed in principle to a federation of their existing provinces and agreed to meet the next month in Quebec City to hammer out the details. In October 1864, representatives drafted 72 resolutions that would form the basis for the eventual British North America Act, 1867. The legislatures of Canada (Ontario and Quebec), New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia approved the resolutions. Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland opted to stay out of the new federation at that time. The action moved to London, England, where in December 1866 the representatives from the four provinces approved the resolutions. The British Colonial Office then converted the resolutions into the text of a law that would be passed by the British Parliament.

Rex Woods, Fathers of Confederation.

The law that created the country of Canada was called the British North America Act, 1867. We often refer to it simply as the BNA Act. In 1982, it was renamed the Constitution Act, 1867. The BNA Act was passed by the British Parliament (Westminster) because Canada was a British colony. The process of creating the federation of the four provinces of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick became known as “Confederation.” The official name for Canada in 1867 was “the Dominion of Canada” with the idea that former colonies such as Canada, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand were to be considered “self-governing dominions.” They weren’t colonies ruled from London, but they weren’t completely independent either. Thus, when Canada was founded in 1867, there was no such thing as Canadian citizenship and Britain was still in charge of foreign affairs. There was no mention of a Supreme Court for Canada in 1867 because appeals were still made to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London.

New provinces and territories later joined Confederation: Manitoba (1870); Northwest Territories (1870); British Columbia (1871); Prince Edward Island (1873); Yukon (1898); Saskatchewan (1905); and Alberta (1905). Newfoundland did not join Confederation until 1949 (it was renamed Newfoundland and Labrador in 2001). Nunavut was carved out of the Northwest Territories and became a territory in 1999.

The First Fifty Years after Confederation

The dominant themes in Canadian constitutional history for the first fifty years were the division of powers between the federal and provincial governments and the development of increasing independence from Great Britain.

A book titled Constitutional Issues in Canada 1900–1931 gives a sense of the issues of the day. Many of the issues mentioned there will still be familiar today. The text contains chapters on the unwritten constitution, constitutional amendment and development, the governor general, the Cabinet, the House of Commons, the Senate, the civil service, political parties, and dominion-provincial relations.[2] Specific topics include the independence of the judiciary and the unreformed Senate.

The King-Byng Crisis

In 1926, Canada had a constitutional crisis. It involved a clash between Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King and Governor General Viscount Julian Byng of Vimy. Byng was a First World War hero who had commanded the Canadian Corps — the first Canadian contingent to fight together as a large unit. The bravery and the sacrifice of Canadian soldiers in the First World War (1914–1918) was an important contributor to forging a unique Canadian identity and winning the respect of leaders in London and people around the world. One of the greatest and bloodiest triumphs occurred at the Battle of Vimy Ridge in France in April 1917. General Byng commanded the successful Canadian Corps at Vimy and after the war he was appointed by London as governor general in Canada. Until 1952, governors general were all British citizens, usually former diplomats, politicians, or military men like Byng, and were appointed by London sometimes in consultation with the Canadians, but sometimes not. Although British, Byng was considered a real “Canadian” hero.

Governor General Viscount Byng of Vimy.

Prime Minister Mackenzie King headed a minority government and faced the prospect of losing a vote in the House of Commons, which would have required his government to resign. In a situation somewhat analogous to the prorogation crisis of 2008 (see page 33), Byng refused King’s request for a dissolution of Parliament that would have triggered an election. Instead, Byng called upon the Leader of the Opposition, Arthur Meighen, to form a government. Meighen was unable to command the confidence of the majority in the House of Commons and was forced to ask the governor general to dissolve Parliament. In the ensuing election campaign, King made the constitutional role of the governor general a main issue. This wasn’t the first or the last time that the Constitution would be a main issue in a Canadian election campaign. King won the election and Byng left Canada with his reputation injured. Subsequently, most constitutional scholars have come to defend Byng’s decision as correct.

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King.

In 1931, the British Parliament passed the Statute of Westminster. It provided that the United Kingdom Parliament would no longer pass laws that applied to the dominions like Canada unless the dominion requested and consented to the law. The Statute of Westminster was an important milestone on the road to Canadian independence and it is recognized as forming part of the Canadian Constitution. It paved the way for Canadians to amend our Constitution ourselves, if only we could agree on a mechanism to do so. Finding such agreement would take another five decades.

While the Statute of Westminster cleared the way for Canada to cut the legal umbilical cord with the mother country, we were slow to do so. For example, since Confederation in 1867, the highest court of appeals for Canada was the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, a group of British judges who heard appeals from British colonies and dominions. Appeals to the Judicial Committee were not abolished until 1949 and that body would not actually decide its final Canadian appeal until 1959.

The Quest for “Patriation”

After the end of the Second World War, much energy was spent on the quest for patriation and the search for a made-in-Canada process for amending our Constitution to replace the need to request Great Britain pass legislation in its Parliament every time Canada wanted to amend the BNA Act, 1867. We came to refer to this process as the quest for “a domestic amending formula.” Patriation is a uniquely Canadian word. You won’t find it in dictionaries outside Canada. It refers to the process of making our Constitution our own — of converting the BNA Act from a British law into a wholly Canadian Constitution.

In 1960, Parliament enacted the Canadian Bill of Rights Act. “The Bill” was an ordinary law that applied only to the actions of the federal government. It protected freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and other rights. The Bill was hailed by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker and welcomed by rights advocates. It was not given a very generous interpretation by the courts and, if anything, it strengthened the case of those who argued in favour of a constitutional bill of rights that would apply to all governments in Canada. Thus, within eight years of the Bill’s enactment, Justice Minister Pierre Trudeau published a draft Canadian Charter of Human Rights proposing just that.

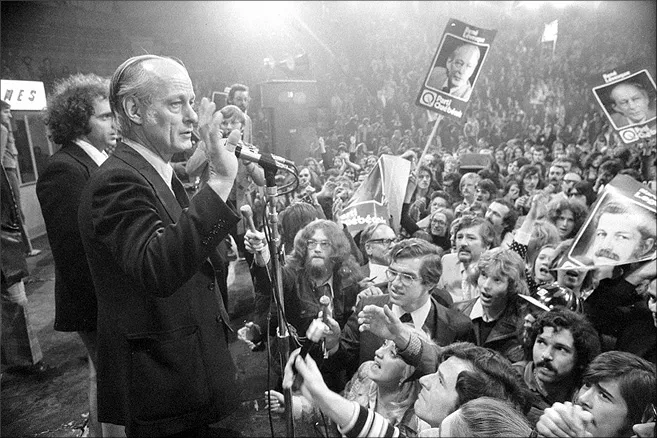

Pierre Elliott Trudeau became prime minister in 1968 and vigorously pursued constitutional reform. An agreement was reached in Victoria in 1971 between Trudeau and the provincial premiers. The Victoria Charter contained a bill of rights and an amending formula. However, the agreement quickly fell apart after Quebec premier Robert Bourassa faced opposition to the Victoria Charter within his home province.

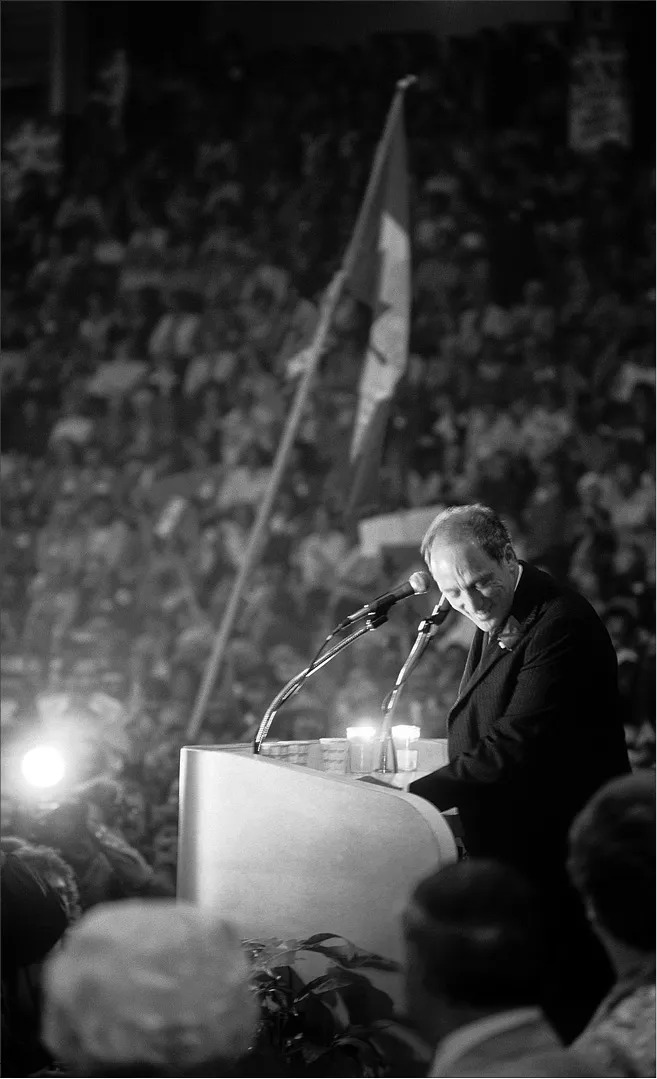

In 1976, the people of Quebec elected the Parti Québécois (PQ) to form a government. The PQ was a separatist party dedicated to achieving independence for Quebec from Canada. In 1980, the PQ held a referendum asking the people for a mandate to enter into negotiations with the Government of Canada towards some form of independence for Quebec, which was called “sovereignty-association.” The charismatic premier of Quebec, René Lévesque, led the “Yes” side in the referendum and the equally charismatic Prime Minister of Canada, Pierre Trudeau, led the “No” side. Trudeau promised Quebeckers that he would work towards “a renewed federalism” after the referendum. Trudeau’s “No” side won by almost 60 percent to 40 percent. This sparked an active and intense period of constitutional negotiations and proposals.

Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

Quebec Premier René Lévesque.

The federal government led the charge for constitutional reform. Many of the provinces opposed Trudeau’s proposals or had strong hesitations. The prime minister and the premiers of the provinces (known as “First Ministers”) met at many First Ministers’ conferences during this time to try to reach an agreement on patriation. Trudeau’s package of constitutional reforms had three key elements: (1) patriation of the Canadian Constitution; (2) a domestic amending formula; and (3) a charter of rights and freedoms. This third aspect — the idea of a constitutionally protected charter or bill of rights — captured the hearts and minds of many Canadians. It was dubbed “the People’s Package.”

Patriation and the People’s Package

With continued opposition from most of the provincial premiers, Trudeau decided to proceed unilaterally. The federal government published a draft “resolution” for the House of Commons and the Senate containing the three items of Trudeau’s constitutional package. In October 1980, the federal government created a Joint Committee of the Senate and the House of Commons on the Constitution and referred this draft to the committee for debate and consideration. Usually the members of the House of Commons and the members of the Senate work separately; however, from time to time, Parliament does create joint committees of both Houses of our Parliament to study important issues. It had happened on several occasions before to study proposed constitutional reforms, but the work of this Joint Committee in the fall of 1980 and winter of 1981 was special.

The Joint Committee worked at a frantic pace over the course of fewer than four months between November 1980, when it commenced hearings, and February 1981, when it completed its work and reported back to Parliament. It heard from nearly a hundred groups during this time and received several hundred written submissions. The hearings were televised in their entirety and widely reported in the media. They galvanized public support for the proposed charter and they brought important segments of the Canadian public into the constitutional reform process. The list of groups that appeared before the Joint Committee included: the Advisory Council on the Status of Women, the Afro-Asian Foundation of Canada, Algonquin Council, Alliance for Life, Canadian Association for the Mentally Retarded, Canadian Bar Association, Canadian Council on Children and Youth, Canadian Jewish Congress, Council of Quebec Minorities, la Fédération des francophones hors Quebec, Federation of Saskatchewan Indians, German-Canadian Committee on the Constitution, Indian Rights for Indian Women, National Action Committee on the Status of Women, National Association of Japanese Canadians, National Black Coalition of Canada, Native Women’s Association of Canada, Ontario Association of Catholic Bishops, Ukrainian Canadian Committee, Vancouver People’s Law School Society, and World Federalists of Canada — Operation Dismantle.[3] For the first time, these groups became constitutional participants, not merely observers.

The process that culminated in the enactment of the Constitution Act, 1982 was a unique exercise in citizen participation in constitutional reform. Prior to November 1980, constitutional reform had always been a strictly elitist government endeavour, captured by the term executive federalism. Citizens or citizen groups did not have “a seat at the table,” but rather were passive recipients of the news of whatever proposal the elected leaders of federal and provincial governments were debating. Citizen groups contributed to the enactmen...