![]()

CHAPTER I. — THE RELATION OF SOCIETY TO THE CONVICT.

A prison is a cross section of society in which every human strain is clearly revealed. An average prison, and its inmates, in point of character, intelligence and habits, will compare favorably with any similar number of persons outside of prison walls.

I believe that my enemies, as well as my friends, will concede to me the right to arrive at some conclusions with respect to prisons and prisoners by virtue of my personal experience, for I have been an inmate of three county jails, one state prison and one federal penitentiary. A total of almost four years of my life has been spent behind the bars as a common prisoner; but an experience of such a nature cannot be measured in point of years. It is measured by the capacity to see, to feel and to comprehend the social significance and the human import of the prison in its relation to society.

In the very beginning I desire to stress the point that I have no personal grievance to air as a result of my imprisonment. I was never personally mistreated, and no man was ever brutal to me. On the other hand, during my prison years I was treated uniformly with a peculiar personal kindliness by my fellow-prisoners, and not infrequently by officials. I do not mean to imply that any special favors were ever accorded me. I never requested nor would I accept anything that could not be obtained on the same basis by the humblest prisoner. I realized that I was a convict, and as such I chose to share the lot of those around me on the same rigorous terms that were imposed upon all.

It is true that I have taken an active part in public affairs for the past forty years. In a consecutive period of that length a man is bound to acquire a reputation of one kind or another. My adversaries and I are alike perfectly satisfied with the sort of reputation they have given me. A man should take to himself no discomfort from an opinion expressed or implied by his adversary, but it is difficult, and often-times humiliating to attempt to justify the kindness of one’s friends. When my enemies do not indulge in calumny I find it exceedingly difficult to answer their charges against me. In fact, I am guilty of believing in a broader humanity and a nobler civilization. I am guilty also of being opposed to force and violence. I am guilty of believing that the human race can be humanized and enriched in every spiritual inference through the saner and more beneficent processes of peaceful persuasion applied to material problems rather than through wars, riots and bloodshed. I went to prison because I was guilty of believing these things. I have dedicated my life to these beliefs and shall continue to embrace them to the end.

My first prison experience occurred in 1894 when, as president of the American Railway Union I was locked up in the Cook County Jail, Chicago, because of my activities in the great railroad strike that was in full force at that time. I was given a cell occupied by five other men. It was infested with vermin, and sewer rats scurried back and forth over the floors of that human cesspool in such numbers that it was almost impossible for me to place my feet on the stone floor. Those rats were nearly as big as cats, and vicious. I recall a deputy jailer passing one day with a fox-terrier. I asked him to please leave his dog in my cell for a little while so that the rat population might thereby be reduced. He agreed, and the dog was locked up with us, but not for long, for when two or three sewer rats appeared the terrier let out such an appealing howl that the jailer came and saved him from being devoured.

I recall seeing my fellow inmates of Cook County Jail stripping themselves to their waists to scratch the bites inflicted by all manner of nameless vermin, and when they were through the blood would trickle down their bare bodies in tiny red rivulets. Such was the torture suffered by these men who as yet had been convicted of no crime, but who were awaiting trial. I was given a cell that a guard took the pains to tell me had been occupied by Prendergast, who assassinated Mayor Carter H. Harrison. He showed me the bloody rope with which Prendergast had been hanged and intimated with apparent glee sparkling in his eyes that the same fate awaited me. His intimation was perhaps predicated upon what he read in the newspapers of that period, for my associates and I were accused of every conceivable crime in connection with that historic strike. I was shown the cells that had been occupied by the Chicago anarchists who were hanged, and was told that the gallows awaited the man in this country who strove to better the living conditions of his fellowmen.

Such was my introduction to prison life. I can never forget the sobbing and screaming that I heard, while in Cook County Jail, from the fifty or more women prisoners who were there. From that moment I felt my kinship with every human being in prison, and I made a solemn resolution with myself that if ever the time came and I could be of any assistance to those unfortunate souls, I would embrace the opportunity with every ounce of my strength. I felt myself on the same human level with those Chicago prisoners. I was not one whit better than they. I felt that they had done the best they could with their physical and mental equipment to improve their sad lot in life, just as I had employed my physical and mental equipment in the service of those about me, to whom I was responsible, whose lot I shared,—and the energy expended had landed us both in jail. There we were on a level with each other.

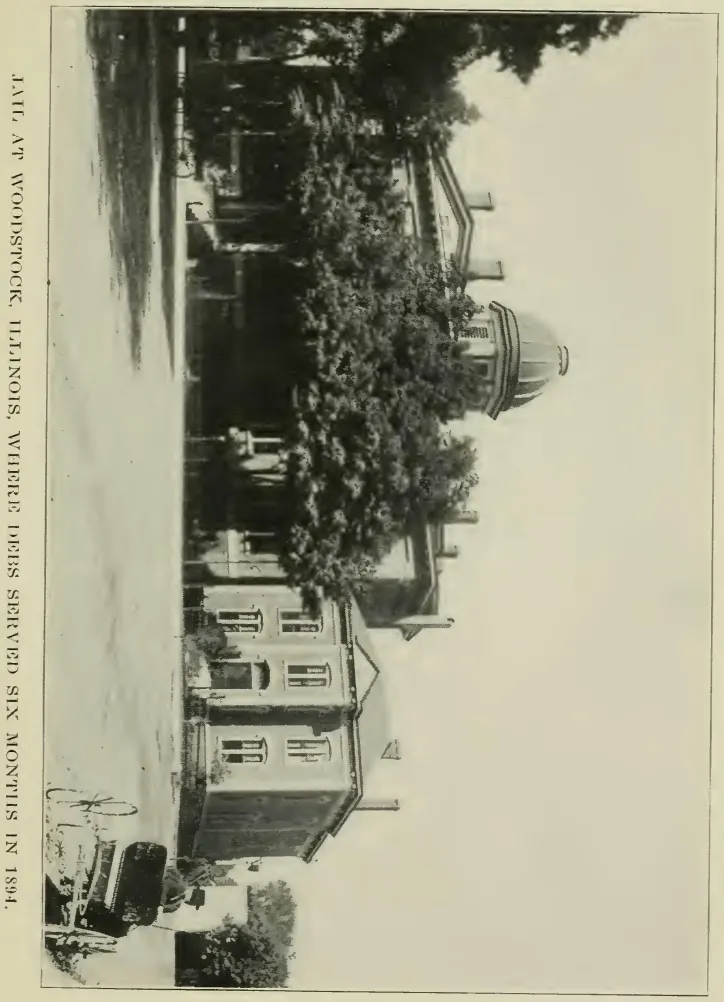

With my associate officers of the American Railway Union I was transferred to the McHenry County Jail, Woodstock, Illinois, where I served a six months’ sentence in 1895 for contempt of court in connection with the federal proceedings that grew out of the Pullman strike in 1894. My associates served three months, but my time was doubled because the federal judges considered me a dangerous man and a menace to society. In the years that intervened some national attention was paid to me because I happened to have been named a presidential candidate in several successive campaigns.

But there was no real rejoicing from the influential and powerful side of our national life until June, 1918, when I was arrested by Department of Justice agents in Cleveland for a speech that I had delivered in Canton, Ohio. I was taken to the Cuyahoga County Jail, and when the inmates heard that I was in prison with them there was a mild to-do about it, and they congratulated me through their cells. A deputy observed the fraternity that had sprung up, and I was removed to a more remote corner. Just after I retired that Sunday midnight I heard a voice calling my name through a small aperture and inquiring if I were asleep. I replied no.

“Well, you’ve been nominated for Congress from the Fifth District in Indiana. Good luck to you!” he said.

When a jury in the federal court in Cleveland found me guilty of violating the Espionage Law, through a speech delivered in Canton on June 16, 1918, Judge Westenhaver sentenced me to serve ten years in the West Virginia State Penitentiary, at Moundsville. This prison had entered into an agreement with the government to receive and hold federal prisoners for the sum of forty cents per day per prisoner. On June 2, 1919, the State Board of Control wrote a letter to the Federal Superintendent of Prisons complaining that my presence had cost the state $500 a month for extra guards and requested that the government send more federal prisoners to Moundsville to meet this expense. The government could not see its way clear to do this, since it was claimed there was plenty of room at Atlanta, and if, as the State Board of Control averred, I was a liability rather than an asset to the State, the government would transfer me to its own federal prison at Atlanta, which it did on June 13, 1919, exactly two months after the date on which I began to serve my ten years imprisonment—a sentence which was commuted by President Warren G. Harding on Christmas day, 1922.

I was aware of a marvelous change that came over me during and immediately after my first incarceration. Before that time I had looked upon prisons and prisoners as a rather sad affair, but a condition that somehow could not be remedied. It was not until I was a prisoner myself that I realized, and fully comprehended, the prison problem and the responsibility that, in the last analysis, falls directly upon society itself.

The prison problem is directly co-related with poverty, and poverty as we see it today is essentially a social disease. It is a cancerous growth in a vulnerable spot of the social system. There should be no poverty among hard-working people. Those who produce should have, but we know that those who produce the most—that is, those who work hardest, and at the most difficult and most menial tasks, have the least. But of this I shall have more to say. After all, the purpose of these chapters is to set forth the prison problem as one of the most vital concerns of present day society. A prison is an institution to which any of us may go at any time. Some of us go to prison for breaking the law, and some of us for upholding and abiding by the Constitution to which the law is supposed to adhere. Some go to prison for killing their fellowmen, and others for believing that murder is a violation of one of the Commandments. Some go to prison for stealing, and others for believing that a better system can be provided and maintained than one that makes it necessary for a man to steal in order to live.

The prison has always been a part of human society. It has always been deemed an essential factor in organized society. The prison has its place and its purpose in every civilized nation. It is only in uncivilized places that you will not find the prison. Man is the only animal that constructs a cage for his neighbor and puts him in it. To punish by imprisonment, involving torture in every conceivable form, is a most tragic phase in the annals of mankind. The ancient idea was that the more cruel the punishment the more certain the reformation. This idea, fortunately, has to a great extent receded into the limbo of savagery whence it sprang. We now know that brutality begets brutality, and we know that through the centuries there has been a steady modification of discipline and method in the treatment of prisoners. I will concede that the prison today is not nearly as barbarous as it was in the past, but there is yet room for vast improvement, and it is for the purpose of causing to be corrected some of the crying evils that obtain in present day prisons and making possible such changes in our penal system as will mitigate the unnecessary suffering of the helpless and unfortunate inmates that I set myself the task of writing these articles before I turn my; attention to anything else.

It has been demonstrated beyond cavil that the more favorable prison conditions are to the inmates, the better is the result for society. We should bear in mind that few men go to prison for life, and the force that swept them into prison sweeps them out again, and they must go back into the social stream and fight for a living. I have heard people refer to the “criminal countenance”. I never saw one. Any man or woman looks like a criminal behind bars. Criminality is often a state of mind created by circumstances or conditions which a person has no power to control or direct; he may be swamped by overwhelming influences that promise but one avenue to peace of mind; in sheer desperation the distressed victim may choose the one way, only to find he has broken the law—and at the end of the tape loom the turrets of the prison. Once a convict always a convict. That is one brand that is never outworn by time.

How many people in your community would be out of prison if they would frankly confess their sins against society and the law were enforced against them?

How many lash and accuse themselves of nameless and unnumbered crimes for which there is no punishment save the torment visited upon the individual conscience? Yet, they who so accuse themselves, assuming there exist reasons to warrant accusation, would never admit to themselves the possession of a criminal countenance. In Atlanta Prison I made it a point to seek out those men that were called “bad”. I found the men, but I did not find them bad. They responded to kindness with the simplicity of a child. In no other institution on the face of the earth are men so sensitive as those who are caged in prison. They are oft-times terror-stricken; they do not see the years ahead which may be full of promise, they see only the walls and the steel bars that separate them from their loved ones. I never saw those bars nor the walls in the nearly three years that I spent in Atlanta. I was never conscious of being a prisoner. If I had had that consciousness it would have been tantamount to an admission of guilt, which I never attached to myself.

It was because I was oblivious of the prison as a thing that held my body under restraint that I was able to let my spirit soar and commune with the friends of freedom everywhere. The intrinsic me was never in prison. No matter what might have happened to me I would still have been at large in the spirit. Many years ago, when I made my choice of what life had to offer, I realized, saw plainly, that the route I had chosen would be shadowed somewhere by the steel bars of a prison gate. I accepted it, and understood it perfectly. I consider that the years I spent in prison were necessary to complete my particular education for the part that I am permitted to play in human affairs. I would certainly not exchange that experience, if I could, to be President of the United States, although some people indulge the erroneous belief that I have coveted that office in several political campaigns.

The time will come when the prison as we now know it will disappear, and the hospital and asylums and farm will take its place. In that day we shall have succeeded in taking the jail out of man as well as taking man out of jail.

Think of sending a man out from prison and into the world with a shoddy suit of clothes that is recognized by every detective as a prison garment, a pair of paper shoes, a hat that will shrink to half its size when it rains, a railroad ticket, a five dollar bill and seven cents carfare! Bear in mind that the railroad ticket does not necessarily take a man back into the bosom of his family, but to the place where he was convicted of crime. In other words a prisoner, after he has served his sentence, goes back to the scene of his crime. Society’s responsibility ends there—so it thinks. But does it? I say not. With the prison system what it is, with my knowledge of what it does to men after they get into prison, and with the contempt with which society regards them after they come out, the wonder is not that we have periodical crime waves in times of economic and industrial depression, but the wonder is that the social system is not constantly in convulsions as a result of the desperate deeds of the thousands of men and women who pour in and pour out of our jails and prisons in never ending streams of human misery and suffering.

But society has managed to protect itself against the revenge of the prisoner by dehumanizing him while he is in prison. The process is slow, by degrees, like polluted water trickling from the slimy mouth of a corroded and encrusted spout—but it is a sure process. When a man has remained in prison over a certain length of time his spirit is doomed. He is stripped of his manhood. He is fearful and afraid. He has not been redeemed. He has been crucified. He has not reformed. He has become a roving animal casting about for prey, and too weak to seize it. He is often too weak to live even by the law of the fang and the claw. He is not acceptable even in the jungle of human life, for the denizens of the wilderness demand strength and bravery as the price and tax of admission.

Withal, a prison is a most optimistic institution. Every man somehow believes that he can “beat” his sentence. He relies always upon the “technical point” which he thinks has been overlooked by his lawyers. He sometimes imagines that fond friends are busily working in his behalf on the outside. But in a little while the bubble breaks, disillusion appears, the letters from home become fewer and fewer, and the prisoner in tears of desperation resigns himself to his lot. Society has won in him an abiding enemy. If, perchance, he is not wholly broken by the wrecking process by the time his sentence is served, he may seek to strike back. In either case society has lost.

I do not know how many prisoners came to me with their letters soaked in tears. They sought my advice. They believed I could help them over the rough edges. I could do nothing but listen and offer them my kindness and counsel. They would stop me in the corridors, and on my way to the mess room and say: “Mr. Debs, I want to get a minute with you to tell you about my case”. Or, “Mr. Debs, will you read this letter from my wife; she says she can’t stand the gaff any longer”. Or, “Mr. Debs, my daughter has gone on the town; what in God’s name can you do about it?” What could I do about it? I could only pray with all my heart for strength to contribute toward the rearrangement of human affairs so that this needless suffering might be abolished. Two or three concrete cases will suffice as examples of the suffering that I saw.

Jenkins, but that is not his name, was a railroad man. Aged, 35. Married and six children; the oldest a daughter, aged 16 years. His wages were too small to support his family in decency. He broke into a freight car in interstate commerce. Sentenced to five years in Atlanta. He received a letter a little while before his term expired telling him that his daughter had been seduced and was in the “red light” district. This man came to me with his tears and swore he would spend the rest of his life t...