![]() PART ONE

PART ONE

WHY IS DIVERSITY IMPORTANT IN THE NEW MILLENNIUM?![]()

1

DIVERSITY IN THE NEW ECONOMY

Navigating the Perfect Storm

I began this book with President Barack Obama’s inspiring remarks from a 2009 speech to a Joint Session of Congress. But these comments offered more than a somber assessment of the discouraging state of American education: they were a call to action. The President argued that in order to compete globally, significantly more Americans will need to obtain a college degree. And yet current trends suggest that only 46.4 percent of people in the critical 25–34 age demographic will have earned a college degree by 2020, leaving the nation nearly 24 million degrees short of the 60 percent needed to surpass countries like South Korea and Japan (Nichols, 2011). This degree shortfall, along with changing demographics and an increasingly turbulent political landscape, has created a “perfect storm” for leaders contemplating the role of diversity in higher education. To understand and overcome the challenges of this perfect storm, academic leaders must fundamentally reframe how they approach issues of diversity in our colleges and universities.

They are not alone. In colleges and universities, corporations and nonprofits, the challenge presented by today’s global economy requires a conceptual shift in our understanding of why diversity matters (Beckham, 2008). As scholars have noted, diversity has become a vital economic asset. In short, it offers a means to improve an institution’s bottom line. Moreover, this “bottom line” encompasses more than economic performance. Researchers have shown conclusively that a more diverse community improves learning and problem solving, enhances research and innovation, and strengthens organizational culture and teamwork (Cox, 1991; Milem, Chang, & Antonio, 2005; Paige, 2007; D. A. Thomas, 2004). These outcomes are increasingly cited by those seeking to promote diversity in both the workplace and the academy.

The Five Pressure Systems Powering the Perfect Storm

This chapter seeks to help academic leaders understand some of the most important social and economic issues confronting colleges and universities today. Operating from the assumption that academic institutions are open systems in constant exchange with the wider environment (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978), the chapter posits that organizational boundaries are shifting and permeable, simultaneously penetrating and being penetrated by the broader social sphere. Because campuses do not exist in a vacuum, they cannot be fixed in a vacuum. We all need to become more responsive to a changing world and particularly to new pressures that are exerting themselves on higher education.

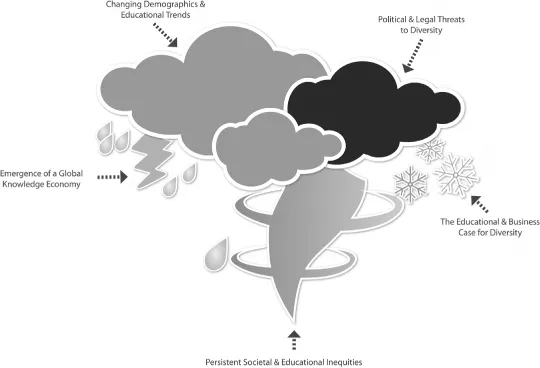

Although it is beyond the scope of this book to address every relevant external factor, this chapter outlines five critical pressures powering the perfect storm highlighting diversity’s importance in the new millennium: (a) the emergence of a knowledge-based global economy; (b) changing demographics; (c) persistent educational inequalities along racial, ethnic, and gender lines; (d) the crystallization of the importance of diverse experiences, both within and outside the classroom, for all students as an educational and workforce imperative; and (e) continuing legal and political threats to diversity and affirmative action (Figure 1.1). Unless we broaden our approach to issues of diversity, we risk a future in which diverse students and groups will feel marginalized on campus and all graduates, whatever their background, will emerge from college without the necessary skills to compete in the global economy. By contrast, if we can comprehend the power of these critical pressures, and chart our way accordingly, we can foster positive, transformative change, not only in our institutions of higher learning, but throughout American society.

Pressure One: The Emergence of a Knowledge-Based Global Economy

As President Obama noted, in today’s economy, a secondary education is no longer a luxury; it is a prerequisite. The Great Recession1 has only amplified the need for a more educated workforce, as the economic downturn has hit the educationally disadvantaged hardest, especially Asian Americans, African Americans, Latinos, older workers, and young people (Carnevale, Smith, & Strohl, 2010). Our ability to recover will depend on preparing students for a world where nearly two-thirds of new jobs in the next decade will require at least some college education. This new economy will be powered not by machines, but by highly educated people. In a lecture delivered to a national meeting of the Society of College and University Planning, President Emeritus James Duderstadt of the University of Michigan stated:

Just as the space race of the 1960s stimulated major investments in research and education, there are early signs that the skills race of the twenty-first century may soon be recognized as the dominant domestic policy issue facing our nation. But there is an important difference here. The space race galvanized public concern and concentrated national attention on educating “the best and brightest,” the elite of our society. The skills race of the twenty-first century will value instead the skills and knowledge of our entire workforce as a key to economic prosperity, national security, and social wellbeing. (Duderstadt, 2000, p. 5)

FIGURE 1.1

The Perfect Storm Powering Diversity’s Emergence as a Strategic Priority

Over the past several decades, the Midwestern region where the author grew up has experienced steep declines in manufacturing, leading to a sharp rise in poverty, crime, and other social problems. As the Internet and other knowledge-based resources like information technology and intellectual property have emerged, what Daniel Pink calls “creative jobs” have become the fastest growing sector of the U.S. economy (Pink, 2005). Creative jobs in graphic and web design, sales and marketing, accounting and management, health care, law, and teaching require the ability to use information in dynamic and imaginative ways.

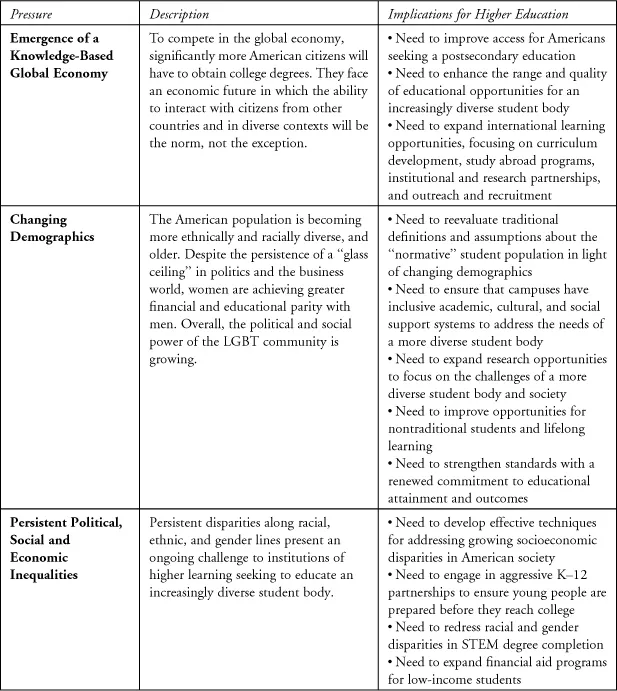

TABLE 1.1

Strategic Pressures and Their Implications for Higher Education Diversity Initiatives

Low-paying service jobs are now a last, dwindling opportunity for those without some form of higher education. Indeed, during the past 30 years all net job growth has occurred in sectors that require at least some form of postsecondary education (Symonds, Schwartz, & Ferguson, 2011). One obvious indicator of the widening gap between high school and college graduates is their income disparity. As it stands today, the lifetime earning gap between a high school and college graduate is now more than $1 million and growing (Symonds et al., 2011). To say that the prospects are daunting for individuals without a college education is an understatement.

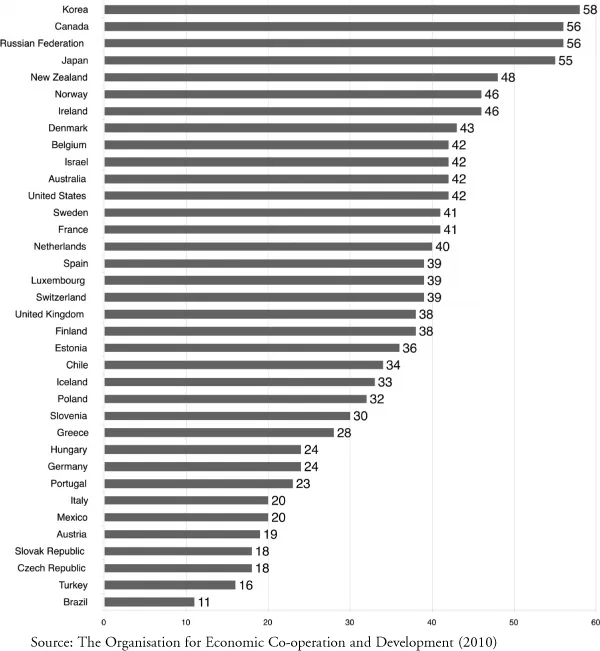

Around the world, higher learning institutions are responding to the new reality. Unfortunately, trends examined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development suggest that the United States has lost its historic edge in adults with a college degree (Figure 1.2). Particularly with respect to adults aged 25–34, the United States currently ranks twelfth globally at 41.6 percent (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2010). The United States also has the lowest graduation rates among those students who actually enroll in college as compared with other developed nations (OECD, 2010). Meanwhile, countries like Canada (56 percent), Japan (55 percent), and South Korea (58 percent) are ahead and pulling away. Catching up with these nations will require a tremendous commitment from all levels of American society.

To make significant headway, the United States must address disparities in educational opportunity and achievement, particularly among historically underrepresented African American, Latino, Native American, and first-generation students. The challenge has become more daunting, however, in light of the fact that higher learning itself is undergoing a revolution. It is no longer simply about getting student bodies into the classroom. Now it is about creating opportunities for students to leave the classroom, whether on study abroad programs or into online learning communities that transcend state and national borders. The Internet has opened new avenues to information and helped lower the constraints of time and space for collaborating locally and globally. It has made communication simpler and faster. But colleges and universities must do more to provide students with the training and resources they need to thrive in the web-powered working environments of the future.

Pressure Two: Changing Demographics

A second pressure driving the “perfect storm” is the changing face of American society. For years, demographers have tracked the growth of minority populations and the fact that America’s population will reach a “minority majority” tipping point during this century. The future is approaching quickly, and this demographic shift offers an unparalleled opportunity to diversify our campuses even as our emerging knowledge-based, global economy demands a similar reframing of diversity’s importance in this new reality.

FIGURE 1.2

Percentage of Population Ages 25–34 With a College Degree by Country in 2008

Racial and Ethnic Trends

Taken together, ethnic and racial minorities—those who identify themselves as non-White—account for most of the nation’s population growth among people 18 and younger (Frey, 2011a).2 From 2000 to 2010, the population of White youth under the age of 18 declined by 4.3 million, while the population of Latino and Asian youth grew by 5.5 million. The accelerated growth of this “new minority”3 heralds an increasingly diverse labor force (Frey, 2011a). Although this demographic shift presents obvious challenges, it also offers a number of clear advantages, not only because other developed nations are experiencing slower growth rates, but because their populations lack our diversity. Box 1.1 explores the challenge of undocumented students in higher education.

BOX 1.1

An Emerging Civil Rights Issue: Undocumented Students in Higher Education

The rising number of undocumented students is presenting a particularly thorny civil rights challenge for colleges and universities. In 2010, an estimated 66,000 undocumented students graduated from high school only to find the doors to secondary education closed. Many of these young people have resided in the United States nearly all their lives and consider this country their home. These young people aspire to contribute their talents to our country.

American law remains ambiguous in its treatment of undocumented students. Since the 1982 Supreme Court case Plyler v. Doe (457 U.S. 202), K–12 education has been guaranteed for all children regardless of their legal status. However, federal law denies undocumented college students access to financial aid and in-state tuition, although individual states have been able to establish their own tailored policies. Between 2001 and 2009, 11 states passed laws allowing undocumented students to pay in-state tuition while attending college: California, Texas, New York, Utah, Washington, Oklahoma, Illinois, Kansas, New Mexico, Nebraska, and Wisconsin. Three of these states, California, New Mexico, and Texas, also allow undocumented students to seek state financial aid (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2011).

In recent years, Alabama, Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Indiana, and South Carolina have taken controversial steps to discourage undocumented students from pursuing a secondary education, much less a college degree. The most extreme measure, a 2011 immigration bill passed in Alabama, explicitly bars undocumented students from attending in-state colleges and requires K–12 school officials to compile and submit lists of suspected undocumented students to state education officials. This policy has led to widespread anxiety among minority communities in Alabama and negative effects on the state’s economy.

The DREAM Act

In 2007, a bipartisan coalition of federal legislators introduced the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act. This legislation would allow undocumented students access to in-state tuition and a pathway to a six-year conditional permanent residency upon the completion of a college degree or two years of military service. Since its introduction, the bill has fallen victim to partisan politics, despite the massive mobilization of student activists and their supporters during the 2010 legislative session.

If passed, the DREAM Act would provide undocumented students with the opportunity to gain a postsecondary education and ultimately become eligible for legal permanent residency, and thus access to a green card and legal employment. Upon completion of further conditions, these residents could eventually apply for full citizenship. Among other benefits, the DREAM Act would also clearly have a positive influence on national dropout rates; because the doors to college are essentially closed to them, undocumented high school students have little incentive to graduate from high school. For more information about the DREAM Act and the various organizations involved in this movement visit http://dreamact.info.

Sources: National Conference of State Legislatures (2011) and Stevenson (2004).4

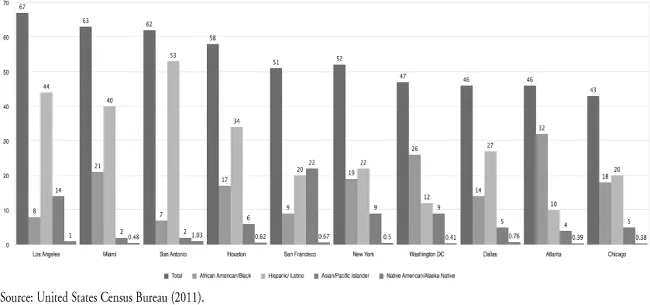

The browning of America is occurring faster than many anticipated (Figure 1.3). Previous demographic studies projected that the overall population would become minority White by 2042, and that the youth population would reach this state by 2023 (Frey, 2011a). Yet the twin engines of immigration and birth rates have led to greater than expected growth among minority populations. For example, in 2009 the birth rate among Whites was 1.9 compared with 3 among Latinos. Looking at trends in immigration, only 15 percent of the growth over the past 10 years was attributable to Whites; Latinos, Asians, and other new minorities accounted for nearly 80 percent (Frey, 2011a). Moreover, this statistic excludes the thousands of undocumented families who have come to the United States in search of better opportunities.

FIGURE 1.3

Race and Ethnicity Populations by Percentage in Major Metropolitan Areas in 2009

Current projections suggest that the demographic tipping point may occur sooner than anticipated and that White children may become a minority population before the next major census in 2020 (Frey, 2011a). In many of our nation’s largest school districts, minorities are already the majority. A recent Brookings Institute analysis reported that 10 states and 35 large metropolitan areas now have minority White youth populations, with major cities like Atlanta, Dallas, Orlando, and Phoenix becoming “minority majority” in recent years (Frey, 2011b). Indeed, recent reports by the U.S. Census Bureau showed that the majority of new births in this country are now nonwhite Hispanic children (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012).

BOX 1.2

Demographic Shifts in the LGBT Community

Although the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community rarely figures prominently in discussions of demographics, this group has a growing voice and its needs have increasingly become a priority in academia. Although their concerns do not necessarily mirror those of other minority groups, the LGBT community deserves a seat at the table in discussions about diversity and inclusion. Indeed, part of the challenge in addressing LGBT concerns stems precisely from the lack of data on its demographic size and make-up. For obvious reasons, many LGBT individuals are reluctant to reveal information about their sexual orientation or gender identity. Nevertheless, the United States 2000 and 2010 censuses counted gay and lesbian individuals and recorded 646,464 same-sex couples in 2010.

Drawing on information from four national and two state-level population-based surveys, the Williams Institute of the University of California–Los Angeles Law School estimated that in 2009 there were around nine million adults in the United States who describe the...