![]()

CHAPTER 1

First Things First — What’s in Question?

Heat without light in biblical matters is less help than light without heat. “On the reliability of the Old Testament.” The two terms of this title deserve to be defined for the purpose of our inquest. For practical purposes the second element, the Old Testament, is readily defined as the particular group of books written in Hebrew (with a few Aramaic passages) that form at one and the same time the basic canon of the Hebrew Bible, or “Tanak” of the Jewish community (Torah, Nebi’im, Kethubim, “Law, Prophets, Writings”), and the basic “Old Testament” (or “former covenant”) of most Christian groups, who add to it (to form their fuller Bible) the briefer group of writings of the Greek New Testament (or “new covenant”), not studied in this book.

Anyone who opens and reads the books of the Hebrew Bible, the Old Testament, will find the essence of a fairly continuous story, from the world’s beginnings and earliest humanity down briefly to a man, Abra(ha)m, founding “patriarch,” from whose descendants there came a family, then a group of clans under the name Israel. He had moved from Mesopotamia (now Iraq) via north Syria into Palestine or Canaan, we are told; and his grandson and family came down to Egypt, staying there for generations, until (under a pharaoh’s oppression) they escaped to Sinai, had a covenant and laws with their deity as their ruler, and moved on via what is now Transjordan back into Canaan. A checkered phase of settlement culminated in a local monarchy; David and Solomon are reputed to have subdued their neighbors, holding a brief “empire” (tenth century B.C.), until this was lost and the realm split into two rival petty kingdoms of Israel (in the north) and Judah (in the south). These lasted until Assyria destroyed Israel by 722 and Neo-Babylon destroyed Judah by 586, with much of their populations exiled into Mesopotamia. When Persia took over Babylon, then some of the captive Judeans (henceforth termed “Jews”) were allowed back to Palestine to renew their small community there during the fifth century, while others stayed on in both Babylonia and Egypt. The library of writings that contains this narrative thread also includes versions of the laws and covenant reputedly enacted at Mount Sinai, and renewals in Moab and Canaan. To which must be added the writings in the names of various spokesmen or “prophets” who sought to call their people back to loyalty to their own god YHWH; the Psalms, or Hebrew hymns and prayers; and various forms of “wisdom writing,” whether instructional or discussive.

That sums up baldly the basic narrative that runs through the Hebrew Bible, and other features included with it. Broadly, from Abram the patriarch down to such as Ezra and Nehemiah who guided the Jerusalem community in the fifth century, as given, the entire history (if such it be) does not precede circa 2000 B.C., running down to circa 400 B.C. Those who most decidedly dismiss this whole story point to the date of our earliest discovered MSS of its texts, namely, the Dead Sea Scrolls of the second century B.C. onward. They would take the most minimal view, that the biblical books were originally composed just before the time of the Dead Sea Scrolls, i.e., in the fourth/third centuries B.C. (end of Persian, into Hellenistic, times). With that late date they would couple an ultralow view of the reality of that history, dismissing virtually the whole of it as pure fiction, as an attempt by the puny Jewish community in Palestine to write themselves an imaginary past large, as a form of national propaganda. After all, others were doing this then. In the third century B.C. the Egyptian priest Manetho produced his Aegyptiaka, or history of Egypt, probably under Ptolemy II,1 and by then so also did Berossus, priest of Marduk at Babylon, his Chaldaika, for his master, the Seleucid king Antiochus I.2 Comparison with firsthand sources shows that these two writers could draw upon authentic local records and traditions in each case. So it is in principle possible to suggest that a group of early Hellenistic Jews tried to perform a similar service for their community by composing the books we now know as the Old Testament or Hebrew Bible.3

The difference is, however, twofold. Factually, the Old Testament books were written in Hebrew — for their own community — right from the start, and were only translated into Greek (the Septuagint) afterward, and again primarily for their own community more than for Greek kings. Also, while Manetho and Berossus drew upon authentic history and sources, this activity is denied to the Jewish writers of the Old Testament. So, two questions here arise. (1) Were the Old Testament books all composed within circa 400-200 B.C.? And (2) are they virtually pure fiction of that time, with few or no roots in the real history of the Near East during circa 2000-400 B.C.?

So our study on reliability of the Old Testament writings will deal with them in this light. Have they any claim whatsoever to present to us genuine information from within 2000-400? And were they originated (as we have them) entirely within, say, 400-200? In this little book we are dealing with matters of history, literature, culture, not with theology, doctrine, or dogma. My readers must go elsewhere if that is their sole interest. So “reliability” here is a quest into finding out what may be authentic (or otherwise) in the content and formats of the books of the Hebrew Bible. Are they purely fiction, containing nothing of historical value, or of major historical content and value, or a fictional matrix with a few historical nuggets embedded?

Merely sitting back in a comfy armchair just wondering or speculating about the matter will achieve us nothing. Merely proclaiming one’s personal convictions for any of the three options just mentioned (all, nothing, or something historical) simply out of personal belief or agenda, and not from firm evidence on the question, is also a total waste of time. So, what kind of test or touchstone may we apply to indicate clearly the reliability or otherwise of Old Testament writers? The answer is in principle very simple, but in practice clumsy and cumbrous. We need to go back to antiquity itself, to go back to 400 B.C., to fly back through the long centuries, “the corridors of time” — to 500 B.C., 700 B.C., 1000 B.C., 1300 B.C., 1800 B.C., 2000 B.C., 3000 B.C., or even beyond — as far as it takes, to seek out what evidence may aid our quest.

All very fine, but we have no H. G. Wells “time machine” as imagined over a century ago. We cannot move lazily across from our armchair into the plush, cushioned seat of the Victorian visionary equivalent of a “flying bedstead,” set the dial to 500 B.C. or 1000 B.C. or 1800 B.C., and just pull a lever and go flying back in time!

No. Today we have other means, much clumsier and more laborious, but quite effective so far as they go. In the last two hundred years, and with ever more refined techniques in the last fifty years, people have learned to dig systematically in the long-abandoned ruins and mounds that litter the modern Near East, and (digging downward) to reach back ever deeper into past time.4 A Turkish fort (temp. Elisabeth I) might reuse a Byzantine church on the ruins of a Roman temple, its foundations dug into the successive levels of (say) Syrian temples of the Iron Age (with an Assyrian stela?), then back to Bronze Age shrines (with Egyptian New Kingdom monuments?), on through the early second (Middle Bronze cuneiform tablets?) and third millennia B.C., and back to full prehistory at the bottom of an ever-more-limited pit. And there would be parallel levels and finds in the surrounding mound, for local ancient palace, houses, and workplaces. But why be content with a theoretical example? In Syria, Mari yielded 20,000 tablets of the eighteenth century B.C., which are still in the course of publication; Ebla, Ugarit, and Emar have yielded more besides. To the north, the Hittite archives as published so far fill over one hundred volumes of cuneiform copies.5 From Mesopotamia, rank upon rank of Sumerian, Babylonian, and Assyrian tablets fill the shelves of the world’s major museums. Egypt offers acres of tomb and temple walls, and a myriad of objects inscribed in her hieroglyphic script. And West Semitic inscriptions continue to turn up in the whole of the Levant. These we know about; but a myriad other untouched mounds still conceal these and other material sources of data totally unknown to us, and wholly unpredictable in detail. Much has been destroyed beyond recall across the centuries; this we shall never recover, and never learn of its significance. So, much labor is involved in recovering as reliably as possible (including technological procedures) original documents and other remains accessible to us, so far as we have power and resources to investigate a fraction of them. But these are authentic sources, real touchstones which (once dug up) cannot be reversed or hidden away again. The one caveat is that they be rightly understood and interpreted; which is not impossible, most of the time.

Therefore, in the following chapters we will go back both to the writings of the Old Testament and to the very varied data that have so far been recovered from the world in which those writings were born, whether early or late. Then the two groups of sources can be confronted with one another, to see what may be found.

In doing this, it is important to note that two kinds of evidence will play their part: explicit/direct and implicit/indirect. Both are valid, a fact not yet sufficiently recognized outside the various and highly specialized Near Eastern disciplines of Egyptology, Nubiology, Assyriology/Sumerology, Hittitology, Syro-Palestinian archaeology, early Iranology, Old Arabian epigraphy and archaeology, and the rest. Explicit or direct evidence is the obvious sort that everyone likes to have. A mention of King Hezekiah of Judah in the annals of King Sennacherib of Assyria, or a state seal-impression (“bulla”) of King Hezekiah or Ahaz or J(eh)otham—these are plain and obvious indications of date, historical role, etc. But implicit or indirect evidence can be equally powerful when used aright. Thus in two thousand years ancient Near Eastern treaties passed through six different time phases, each with its own format of treaty or covenant; there can be no confusion (e.g.) of a treaty from the first phase with one of the third phase, or of either with one from the fifth or sixth phases, or these with each other. Based on over ninety documents, the sequence is consistent, reliable, and securely dated. Within this fixed sequence biblical covenants and treaties equally find their proper places, just like all the others; anomalous exceptions cannot be allowed. And so on.

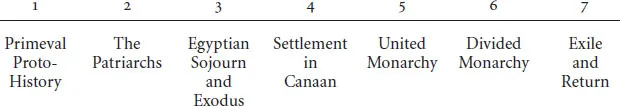

For the purpose of our inquest, the basic Old Testament “story” can be divided conveniently into seven segments, representing its traditional sequence, without prejudice as to its historicity or otherwise.

Table 1. The Seven Segments of Traditional Biblical “History”

But we shall not follow this sequence in numerical order. Instead we shall go to the two most recent “periods” (6 and 7), first to 6, the divided monarchy, which is the period during which the Old Testament accounts are the most exposed, so to speak, to the maximum glare of publicity from external, non-biblical sources, during a period (ca. 930–580 B.C.) of the maximum availability of such evidence to set against the Old Testament data. Then, after tidying up the “tail end,” period 7, we can go back through those long corridors of time (5 back to 1) to consider the case for ever more remote periods in the record, both ancient Near Eastern and biblical, and eventually sum up the inquest.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

“In Medias Res” — the Era of the Hebrew Kingdoms

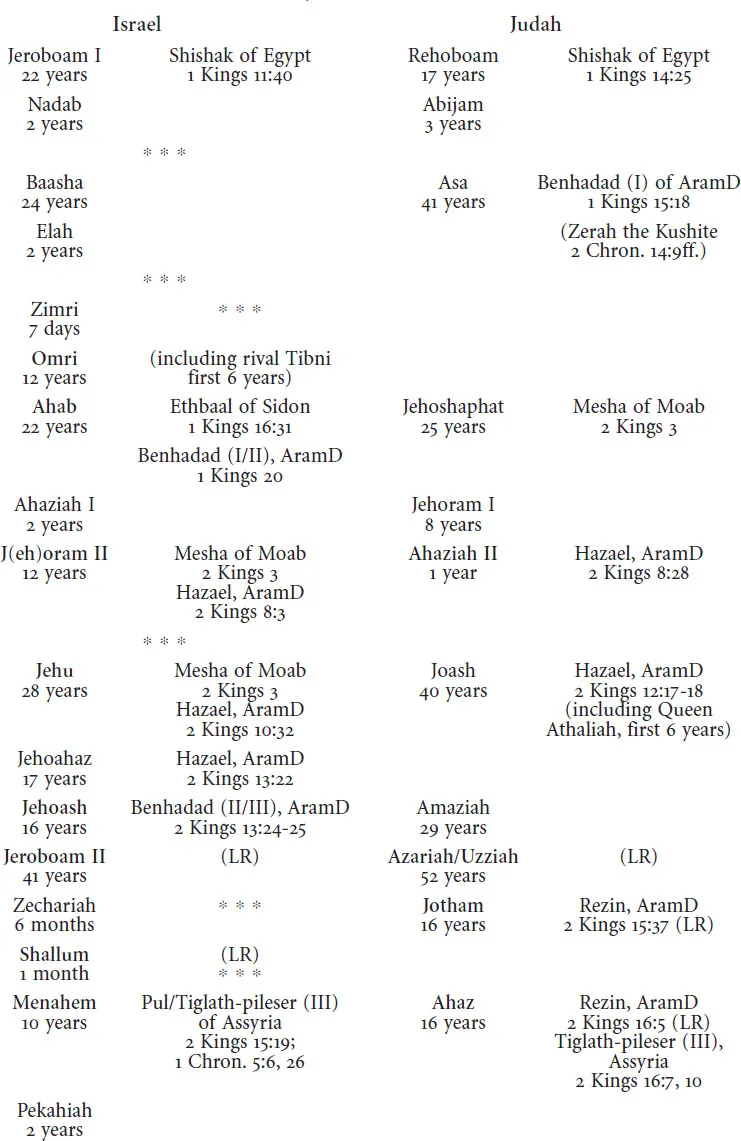

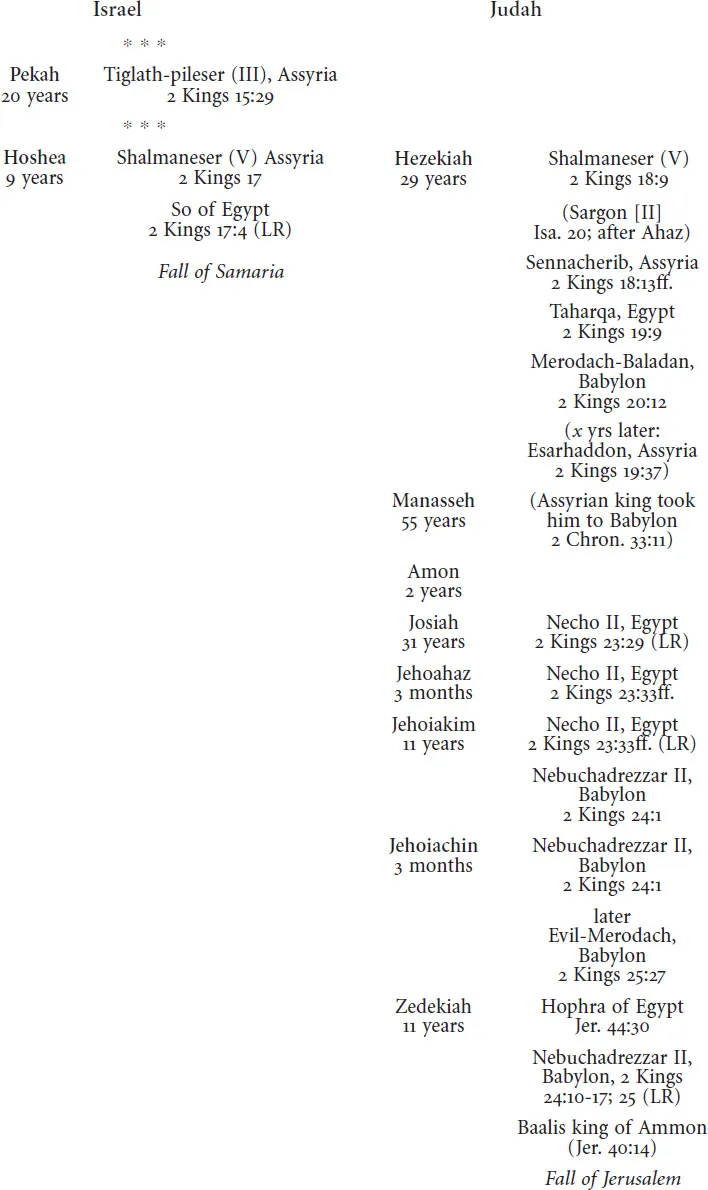

In 1 and 2 Kings and 2 Chronicles we find what is offered as concise annals of the two Hebrew kingdoms, Israel and Judah, that crystallized out of the kingdom of Solomon after his death. In those books we have mention of twenty kings of Israel and twenty kings and a queen regnant in Judah, and also of foreign rulers given as their contemporaries — all in a given sequence. It will be convenient to set out all these people in list form in Table 2 on page 8.

A few notes on this table. Regnal years serve to distinguish between reigns of average length (ca. sixteen years) or over and reigns brief or only fleeting. A string of three asterisks indicates a break between “dynasties” in Israel. “AramD” stands for (the kingdom of) Aram of Damascus. Also, names in bold are for kings involved in external, nonbiblical sources, while “LR” stands for “local (i.e., Hebrew) record” and “possible local record,” as will become clear below.

We shall next proceed by the following steps:

1. To review the foreign kings mentioned in Kings, Chronicles, and allied sources, in terms of their mention in external records.

2. To review, conversely, mentions of Israelite and Judean kings in such external, foreign sources.

3. To review the “local records” (LR) in Hebrew, from Palestine itself, so far as they go.

4. To review concisely the sequences of rulers as given in both the external and biblical sources, and the range of the complex chronology of this period, in the Hebrew Bible and external sources.

5. To review concisely the interlock of historical events, etc., that are attested in both the biblical and external sources.

6. To consider briefly the nature of the actual records we have to draw upon, both in the Bible and the nonbiblical sources.

Table 2. Hebrew Kings and Contemporaries Given by the Biblical Sources

1. ATTESTATION OF FOREIGN KINGS MENTIONED IN THE BIBLICAL RECORD

A. UNTIL THE ASSYRIANS CAME … EGYPT AND THE LEVANT

(i) Shishak of Egypt

In Hebrew Shishaq or Shushaq (marginal spelling) occurs as the name of a king of Egypt who harbored Jeroboam (rebel against Solomon) and invaded Canaan in the fifth year of Rehoboam king of Judah (1 Kings 11:40; 14:25).1 This word corresponds very precisely with the name spelled in Egyptian inscriptions as Sh-sh-n-q or Sh-sh-q. This Libyan personal name is best rendered as Shoshe(n)q in English transcript; it belonged to at least six kings of Egypt within the Twenty-Second/Twenty-Third Dynasties that ruled that land within (at most) the 950-700 time period.2

Of all these kings, Shoshenq II-VI have no known link whatsoe...