eBook - ePub

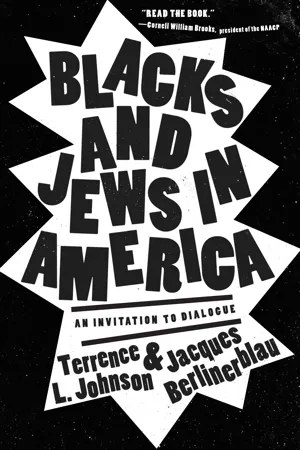

Blacks and Jews in America

An Invitation to Dialogue

Terrence L. Johnson, Jacques Berlinerblau

This is a test

- 224 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Blacks and Jews in America

An Invitation to Dialogue

Terrence L. Johnson, Jacques Berlinerblau

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

A Black-Jewish dialogue lifts a veil on these groups' unspoken history, changing a narrative often dominated by the Grand Alliance and its fracturing. By engaging this history from our country's origins to the present, Blacks and Jews in America models the honest and searching conversation needed for Blacks and Jews to forge a new understanding.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Blacks and Jews in America un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Blacks and Jews in America de Terrence L. Johnson, Jacques Berlinerblau en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Teologia e religione y Religione, politica e Stato. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

Teologia e religioneCategoría

Religione, politica e Stato1

The Afterglow

JB: Terrence, we started writing this book in the middle of a plague, isolated from our students, colleagues, and extended families and from one another. In the midst of it all, the United States imploded because of yet more senseless killings of African Americans. This violence triggered a multiracial group of citizens to take to the streets in some of the largest protests in American history. Just as we finished the first draft of the manuscript for Blacks and Jews in America, Jacob Blake was shot and paralyzed by trigger-happy police in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and two days later a seventeen-year-old white supremacist murdered two people who protested the shooting. We didn’t know that any of this would transpire when we started writing the book based on the class we teach together, “Blacks and Jews in America,” in 2019.

TJ: The 2020 Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests fundamentally altered the direction of our project—and especially for me personally. The worldwide demonstrations against police killings of unarmed Black men and women were astounding. Likewise, the racial and ethnic diversity of folks who joined in solidarity with Black and Brown protestors chanting “Black Lives Matter!” signaled a dramatic turn in the narrative of anti-Blackness. Almost anyone with a pulse could feel George Floyd’s pain through his heartbreaking cry for his deceased mother as a police officer pressed his knee into Mr. Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and forty-six seconds on May 25, 2020. The cold silence following Breonna Taylor’s death in March of that year also vibrated across the nation and world. For the first time in my life, and probably not since the 1960s when the world witnessed police officers routinely beating Black civil rights workers, no one could deny my people’s pain and suffering. Momentarily, the world awakened to Black people’s humanity—finally!

But as I watched demonstrators turn the nation upside down, while I was confined to my home with a walking boot on my left foot and a bandaged right knee, I grew frustrated trying to determine the source of the resounding outcry. Why now? And for how long? I don’t have an answer to these burning questions. Unfortunately, modern history seems to always look upon African Americans with a crooked smile; short-term victories are almost always swallowed by the devil’s advocates. Despite my enduring anger, I cling to the faith of unnamed Black women and men who did not lose their humanity in the face of white supremacy. Their faith and how they translated it into meaningful political action sit at the heart of the historical relationship between Blacks and Jews in North America.

Jacques, what’s at stake for you?

JB: Insofar as my son was protesting and insofar as I actually had the very odd, postmodern, once-in-a-lifetime parenting experience of seeing him live on CNN looking as if he had been tear-gassed, or stoned (or both?), the protests hit home in all sorts of ways. I have always had a certain pride in this country, maybe unexamined, and I certainly have not publicly professed it in too many places. It’s been sort of like, we can course correct, and we are going to get better. “Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will!” as Antonio Gramsci (or Benedetto Croce) said.

But those scenes, starting with the murder of George Floyd, proceeding to that bizarre press conference with the county attorney in Minneapolis (Mike Freeman, I think his name was), and followed by the brutalization of protestors and, of course, President Donald Trump’s power-prance through Lafayette Square with the Bible as shield—all of that led to a reckoning about what America actually is. When I shared my observations with Black colleagues, many said, as kindly as they could, “You just figured this out now?”

TJ: Jacques, as you may recall, we spoke often during the height of the demonstrations, and I routinely recounted to you the same refrain: White communities were mostly silent in July 2014 when Eric Garner in New York City gasped, “I can’t breathe.” Then when Sandra Bland simply asked a belligerent white police officer, “Why am I being pulled over?” on July 10, 2015, she was arrested and died mysteriously three days later in jail. Protestors didn’t storm the streets en masse to decry Bland’s death, unlike what we witnessed after the killings of Floyd and Taylor.

So I repeat: Why now?

JB: I don’t have a good answer. Certainly the coronavirus disease (COVID) lockdown was a factor; it made people focus, because so many were sequestered in their homes. But I’m not sure why so many whites suddenly became engaged, even outraged.

What’s interesting, Terrence, is how many “Blacks and Jews” issues surfaced while all of these distressing events took place in the summer of 2020. For example, the Jewish mayor of Minneapolis, Jacob Frey, was booed out of an event when he said he couldn’t commit to defunding the police.

TJ: There was also Nick Cannon, who experienced backlash in July 2020. When former Public Enemy rapper Professor Griff (Richard Griffin) said on Cannon’s radio show that Jews control the media, Cannon agreed and retorted, “We’re just speaking facts.”

JB: On the brighter side, I think of the ultra-Orthodox Jews in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, who protested on behalf of Black Lives Matter. Given the fraught history of Blacks and Jews in that neighborhood, this was a very promising development.

TJ: We also should note that BLM cofounder Alicia Garza, who is Jewish, played a major role in designing the architecture of today’s progressive politics. Likewise, the passing of Congressman John Lewis in July 2020 prompted the national media to reflect on the relationship between Blacks and Jews. Along with his substantial civil rights platform, Congressman Lewis was remembered for soliciting assistance in 1960 from Jewish students at Vanderbilt University with the sit-ins of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and for cofounding in 1982 the Atlanta Black-Jewish Coalition, which called attention to what some have referred to as the “Grand Alliance” of Blacks and Jews during the civil rights movement. During the brief news cycle, the national media and Twitter turned their attention to the historic encounters between Blacks and (white) Jews: the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Urban League (NUL), and the work of educator and civil rights leader Booker T. Washington and Jewish philanthropist Julius Rosenwald. The men’s collaborative effort established more than five thousand schools for Black children in fifteen states in the South.

JB: As the summer of 2020 progressed, we also learned more about Senator Kamala Harris, who is married to a Jewish American! Joe Biden’s naming her as his running mate raised the specter of Blacks and Jews (and Indian Americans) on Observatory Hill, the vice president’s residence in Washington, DC.

TJ: While writing this book amid this upheaval and calls for change, we also had the opportunity to reassess our work. Whenever friends ask me to describe to them our course, “Blacks and Jews in America,” they all raise two similar questions: Why do you teach this course? And what do you gain from it?

Jacques, I will ask you a similar question: Do you have any personal connections to the subject matter?

JB: I think so. I was conceived in Paris but was born in Maine and grew up in Brooklyn, New York. My immigrant mother was very taken by Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK). It’s something she was nondidactic about, so it took me years to piece together how consistently his name came up in our discussions when I was a child. She’d casually mention him to me here and there. As I recall, her key themes were (1) African American folks had it rough here, and (2) they deserved lots of respect for dealing with insane bigotry. Did my mother know Malcolm? No. She probably still doesn’t know about Malcolm X. It was all MLK, who I guess was a sensation in the French media. Also, her English was terrible, so the only people she could speak to were Haitians in the neighborhood. They were her portal to America.

Brooklyn is a great Black city. Brooklyn is also a great Jewish city. Blacks and Jews milling about, side by side, seems normal to me. When I started my teaching career in the City University of New York system, I was teaching mostly Black and Jewish students.

Eventually I moved to Washington, DC, and I was like, “Where did all the Blacks and Jews go?” At least the side-by-side aspect, I miss it, and maybe that’s why I teach this course. Along the way, I had a jazz apprenticeship, which taught me everything I need to know about the value of work.

What about you, Terrence? Do you have any personal interest in this, or is it more of a pure scholarly pursuit?

TJ: My connection to Blacks and (white) Jews dates back to the Old Testament stories I read and debated in Sunday school in northeastern Indiana. I was told Africans were entangled in the history and bloodlines of David, Abraham, and Solomon. I also knew Jews claimed the same lineage, but that was the extent of my firsthand knowledge of white Jews.

I don’t remember attending school with Jewish kids or living near any Jewish families. Everyone in my immediate world was either a German Lutheran or a Black migrant from the South. Growing up in a small, rural city in Indiana, no one in my immediate world—neither family nor community members—talked about Jews directly.

Strangely enough, I recall a renowned columnist of my hometown newspaper, the late Betty Stein, whom I met when I interned at the paper, but no one ever talked about her being Jewish. I came to know her identity by reading her columns.

Years later I discovered that Indiana’s oldest synagogue dates back to 1848 and is in my hometown, which is known as the City of Churches.

Then, when I went off to Morehouse College, I was shocked to stumble upon white professors at a place where I assumed everyone would be Black. In time, I would get to know them, and many of them were Jewish.

JB: So it seems you had very little face-to-face, person-to-person contact with Jewish people as a young man.

TJ: It was not until years later, when I joined the faculty at Haverford College, that I could understand my experiences within a broader historical context and critically reflect upon them. The idea that I could grow up without any direct knowledge of the Jewish community, which was interwoven in the lives of many African Americans and my own family as our physicians, grocers, teachers, and neighborhood shop owners, is a travesty. It also symbolizes the invisibility of Jews in seats of power and their deep influence in Black America, a historical reality linked to broader domestic and international concerns.

At Haverford College, I found my passion for this scholarly work in a reading group I directed called something like “Israel, Palestine, and Ethical Deliberations.” A white Jewish student from Dayton, Ohio, and a Palestinian student from New York created the syllabus for what would become tough, critical, and honest conversations on how to deal with the mess we’ve inherited. From that moment on, I wanted to emulate the moral and intellectual courage I witnessed in the reading group. The subject “Blacks and (white) Jews in America” is an extension of the many complicated issues we explored in the Haverford reading group on Israel and Palestine.

JB: Our original plan in writing this book was that it would be a follow-up, in a sense, to the important 1995 conversation between Professor Cornel West and Rabbi Michael Lerner titled Jews and Blacks: A Dialogue on Race, Religion, and Culture in America.1 How do you think we are different from these two important figures?

TJ: Cornel West is a hugely important figure in my own intellectual development. In fact, his scholarship carved out a path in the academy for uncounted numbers of African Americans and members of other racial ethnic groups. I often use his theologically inspired pragmatism as a starting point for framing my scholarly questions. What I construct in conversation with his body of work is far more humanist and African inspired than what is evident in West’s imagination. Whereas West employs a prophetic Afro-Christianity to frame his approach to what he calls the “tragic-comic sense of life,” I turn to Africanist-inspired traditions of conjuring, hoodoo, and divination to reconstruct and reimagine Black religion’s role in politics, behind what W. E. B. Du Bois characterized as “the veil of blackness.”

JB: Please tell our readers just a bit about the idea of the “veil of blackness.”

TJ: The veil of blackness is a discourse that prevents whites from seeing Blacks and Black bodies as human, normal, and ordinary.

How are you different from Rabbi Lerner?

JB: Well, first, I am not a rabbi. Nor am I really a man of the Left (or the Right). The rabbi could be very righteous—Torah thunder and all that. I cannot lower that boom. I guess the biggest difference is that, as a secular scholar, my mind tends to gravitate to paradox and irony, whereas the good rabbi understandably inclined to social justice, the Torah, and God’s love. I’m really uncomfortable analyzing problems in theological terms, and for that reason I have less legitimacy to speak “on behalf of” Judaism. I’m just one Jew—a free-floating Jew.

Rabbi Lerner and Professor West were dialoguing in the mid-1990s. From the Black-Jewish angle, how is that moment different from our very turbulent period in American history?

TJ: West and Lerner faced a different, though arg...

Índice

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. The Afterglow

- 2. Finding Our Affinities in a “Blacks and Jews” Dialogue

- 3. Liberalism and the Tragic Encounter between Blacks and White Jews

- 4. Teaching Blacks and Jews in 2020

- 5. Interview with Professor Susannah Heschel

- 6. Interview with Professor Yvonne Chireau

- 7. Talking to American Jews about Whiteness

- 8. The Loop and Minister Farrakhan

- 9. Secularism and Mr. Kicks

- 10. Israel/Palestine

- 11. Afro-Jews

- 12. Outro

- Acknowledgments

- Interviewees

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Authors

Estilos de citas para Blacks and Jews in America

APA 6 Citation

Johnson, T., & Berlinerblau, J. (2022). Blacks and Jews in America ([edition unavailable]). Georgetown University Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3113706/blacks-and-jews-in-america-an-invitation-to-dialogue-pdf (Original work published 2022)

Chicago Citation

Johnson, Terrence, and Jacques Berlinerblau. (2022) 2022. Blacks and Jews in America. [Edition unavailable]. Georgetown University Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/3113706/blacks-and-jews-in-america-an-invitation-to-dialogue-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Johnson, T. and Berlinerblau, J. (2022) Blacks and Jews in America. [edition unavailable]. Georgetown University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3113706/blacks-and-jews-in-america-an-invitation-to-dialogue-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Johnson, Terrence, and Jacques Berlinerblau. Blacks and Jews in America. [edition unavailable]. Georgetown University Press, 2022. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.