![]()

1

CREATION OF COMMUNITY

HOSPITALS AS INTERFACES WITH THE PUBLIC

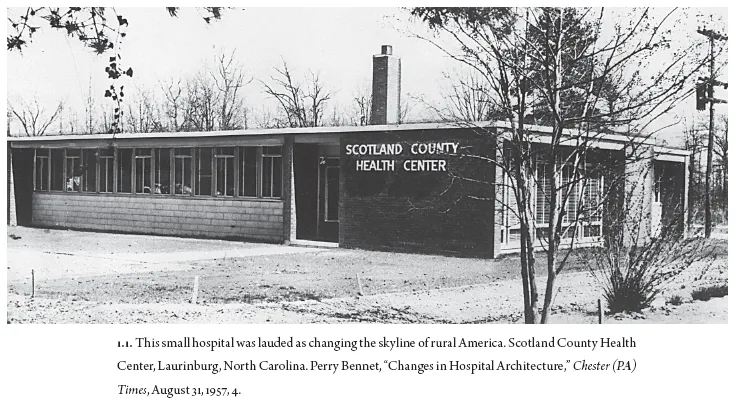

IN 1957 AN EDITORIAL CLAIMED that “a new type of structure is changing the skyline of rural America. It’s the hospital.”1 The simple, single-story hospital in Laurinburg, North Carolina, whose photo accompanied that declaration was not large enough to have had a literal impact on a skyline by itself. The hospital was made of simple materials without adornment: brick, glass, and metal were arranged such that a visitor could clearly see an entry marked by a single column leading to a lobby enclosed with large glass. Beyond the lobby was a line of semi-domestic windows, the exam rooms and patient rooms. Although the Laurinburg hospital was small, it gained significance by association with another eight hundred hospitals built in the United States with funding from the 1946 Hospital Survey and Construction Act or Hill-Burton Act. These eight hundred hospitals would be joined by another four hundred under construction or on the architects’ drawing boards according to a survey by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Readers of the Chester Times, a small-town paper that boasted a circulation of 40,000 near Philadelphia, were told that such hospitals were an unprecedented boon to rural health, considering that farming accidents killed 12,800 farmers and injured 1,050,000 more in 1956. These hospitals would end the “agonizing race over miles of highway” to get a family member to the hospital. A visit from a country doctor was not the same, readers were reminded, because these buildings allowed “intricate laboratory set-ups” and x-ray apparatus to diagnose cancer and tuberculosis. These small hospitals may seem insignificant on their own, but they were part of a massive federal campaign to standardize and spread hospital-based healthcare in the same years as national health insurance experienced a substantive defeat. The unadorned, affordable architecture may also seem insignificant, but these designs were a response to the moods of their communities, crafted with an engagement with the young field of psychology.

Under the Hill-Burton Act, the local population applied for federal funds and raised money to match the federal grants in what has been called a divided welfare state.2 In contrast to communal action, which was controversial in these postwar years, such structures showed that “farmers can raise money as well as wheat.” The public relations coverage showed that such sentiments could describe federal action as a natural extension of rural life. Government set up a framework, but the community was presented as the hospital’s empowered agent, and the article did not mention any fears of communal action. Beneath a photograph of “Liz and Philip,” the queen of England and her consort, on tour of Africa, a photo of the small hospital contributed to the mood of optimism, progress, and unity in the small-town newspaper. Readers were told that farmers hoped these modern buildings in the rural landscape would also help attract skilled doctors who would otherwise have practiced in the city. The hospital building was of symbolic importance, mixing hope and excitement about the new technologies with worry over the costs, indignity, and frightening diagnoses to be endured within its walls.

Many surveys of hospital history jump from the rise of science and technology at the turn of the twentieth century to the challenges of the 1970s and 1980s without examining the rapid expansion of postwar hospitals. Rosemary Stevens, Charles E. Rosenberg, and others describe the rise of hospitals in the late nineteenth century as faced with skepticism if not dread while these institutions transitioned away from a place of resort for those without options, particularly in the case of industrial, maritime, and charity hospitals. Annmarie Adams documents the shift from the pavilion-style hospital intended to prevent the spread of disease, to the vertical hospital, organized to reduce the building’s footprint as well as the distances staff needed to travel within the hospital.3 The post–World War II period has received little attention and is instead typically presented as a peaceful time of federal support and expansion reaching the 1960s where ostensibly Americans had “embraced the hospital as the site of care” without much explanation. Rosenberg begins his account of the rise of hospitals from the nineteenth century to World War I with the statement that hospitals seemed to suddenly become a problem in the late 1960s, without saying much about why.4 Jeanne Kisacky’s history comes to an end with Hill-Burton, mentioning that medical advances were not the key reason for the massive outlay of new hospital construction funding.5 David Sloane and Beverlie Sloane admit that the reasons for the problems of the 1960s “are complicated and not fully understood.”6 The postwar period saw a shift from hospitalized patients to more ambulatory care, and as David Sloane and Allen Brandt observed, this became as significant as the shift from morality to science.7 Ambulatory patients had a choice of whether to bring themselves and their family for care, and often they had a choice of hospitals. These patients were more like consumers than were the charitable cases, a turn that Sloane and Sloane have called medicine’s move to the mall.

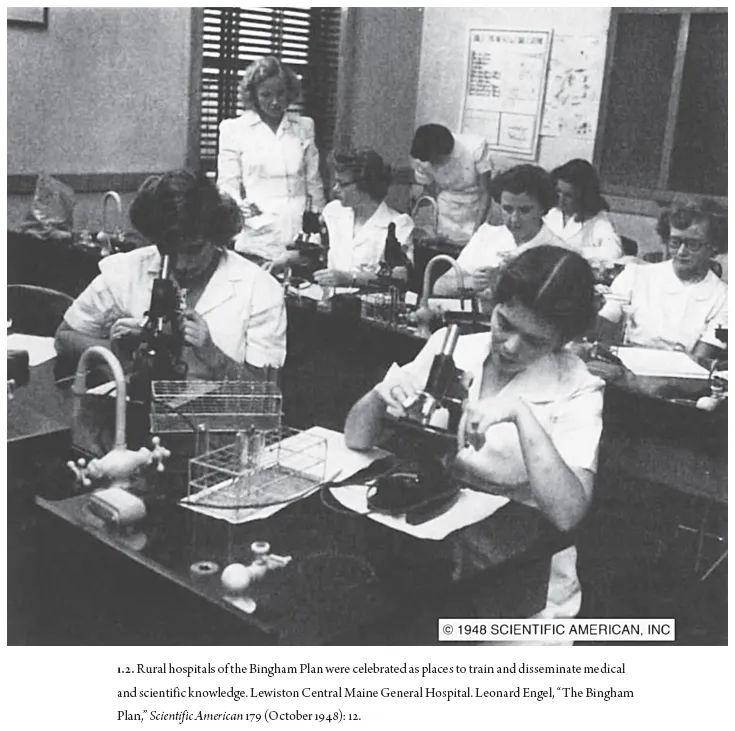

ROOTS IN THE FARM SECURITY ADMINISTRATION OF THE 1930S

Federal attention to the moods and challenges of rural health began with the efforts of the Farm Security Administration and the U.S. Public Health Service. These predecessors of the Hill-Burton Act have been called a rehearsal for a national health system.8 Working with the New Deal era programs, sociologists and bureaucrats studied the challenges in adapting specialized urban hospital care to areas where low population density made it difficult to retain and support specialized doctors. A few hundred beds were deemed necessary to keep a pathologist in residence, even if a good doctor could be convinced to leave the higher pay and other attractions of city life. Rural areas were also less likely to have a university or religious institution to sponsor and run a hospital.9 Alongside these federal efforts, private philanthropy had also been exploring the benefits of consolidating a network of hospitals to help rural Americans, including the Kellogg Foundation in Michigan, the Commonwealth Fund in New York, and the Bingham Plan in New England.10 Federal subsidies continued to work in partnership with private efforts in the divided welfare state to create a national network of hospitals under Hill-Burton.

Looking back on their experience mapping rural health with the Farm Security Administration, Frederick Mott and Milton Roemer describe the landscape as it would have appeared to a traveler in the air.11 The vast surface of the country appears only lightly dotted with towns and villages, concealing the invisible connections to cities that provide markets for the goods grown, trapped, logged, and mined by rural Americans of diverse ethnic, racial, and religious backgrounds. Mott and Roemer explain the effect of increasing industrialization on this landscape as cities have drawn the wealth from the country and left behind a population that, while sick and dying, could find small comfort in knowing that the United States had become one of the wealthiest nations with some of the best medical technology. Thinking about national health from this position, literally aloft, allowed a mixture of such textured, almost poetic commentary coupled with a sociological and numerical type of knowledge. Architecture would come to contribute to this mixture of poetry and data, attending to demographics and aesthetics.

Mott and Roemer’s Rural Health and Medical Care presented a progressive, technological, and paternal view of the problems of rural health. Mott and Roemer painted a compassionate view of the troubled landscape of health in rural America and contextualized the challenges in light of the theory of “cultural lag” outlined by sociologist William Fielding Ogburn. In 1940 the truly rural population was in the minority, as it had been since 1920 or so, when the urban migration inverted the proportion of urban and rural Americans. The authors presented the demographics of the rural population, including many nationalities and races and a high proportion of children, given the high birth rate. The health needs of the population of rural “Negros” in the Southeast and “Indians” in the West received special attention in the book. While acknowledging that city dwellers often idealize life on the American farm, Mott and Roemer explained that the reality includes an “excessive burden of insanity, shortened life expectancy,” and the hardships of agriculture, which may make of the farmer’s wife “a vision, not of youth and beauty, innocence and exuberant health but that of the pale and wan and haggard face.”12 The death rate in towns of fewer than 2,500 residents was the highest in the nation; rural families suffered 20 percent more serious illness that caused them to miss work.13 Expert reports counted further challenges to rural health: poor sanitation, no water infrastructure, poor housing, and poor diet.

Public and private attempts to consolidate and extend hospital care to more of the population were growing slowly when World War II interrupted. Despite a few early attempts at coordination and the Farm Security Administration’s experiment in subsidized insurance, hospitals remained small, private, and often faith-based. Labor unions established some “group hospitalization” plans in the 1920s and 1930s, yielding an increase in the use of hospitals, though some were substandard industrial hospitals. The United States had a relatively low population density compared to other nations and a preponderance of private hospitals at a time when other nations were nationalizing their health systems. The most common form of hospital in the early twentieth-century United States was the voluntary hospital, a mix of charity, free enterprise, and religious good work. Under the vague and highly charged label of volunteerism, these community-based hospitals rarely worked together in a coordinated fashion. These were joined by a few larger hospitals, including a growing number of teaching hospitals associated with universities and a few government-run hospitals for veterans. The large state-run “hospitals for the insane” were also counted among the number of government hospitals.

World Wars I and II distracted attention from governmental social welfare programs and increased the medical and surgical fields in developing technologies and pharmaceuticals while also exposing servicemen and servicewomen to a higher level of medical care.14 These wartime environments favored mobile technologies that could move with units from battlefield to battlefield. X-rays and magnetic bullet detectors returned home along with the mobile surgical units deployed by the medical colleges. These mobile surgical units formed connections with each other and shared what Surgeon A. M. Fauntleroy called the “Hospital Lessons of War.”15 After the wars, hospital construction continued to emphasize efficient operations and cures via surgery and other technologies. Preventative public health efforts such as sanitation, nutrition, and vaccines found it hard to compete with such vivid advances in hospital technologies suited to acute care.

Emerging from the war, it seemed that the time might be right to at last pass national health insurance, but the effort quickly ran into opposition led by the American Medical Association (AMA), which repeatedly played on Cold War fears of communism to defeat it. The idea of national health insurance had been considered in New Deal legislation and was supported by President Franklin Roosevelt and President Harry S. Truman. Truman took up the issue and attempted to mollify the AMA by emphasizing that his plan would increase doctors’ salaries and avoid major structural changes in the American health system.16 But opposition continued mainly in ideological terms that attacked the plan as communist; the secretary of health, education, and welfare opposed “the free distribution of the polio vaccine that Dr. Jonas Salk had developed for children” as “socialized medicine.”17 The mistrust of communal action, ambivalence about government-mandated handouts, and at times overt racism meant that efforts to establish health insurance in the United States were always an uphill battle.18

The AMA launched a major public relations campaign to defeat Truman’s efforts in 1945 and after his reelection in 1948. It hired Whitaker and Baxter, a public relations firm, whose work would continue for years through the most expensive lobbying effort to date, at $1.5 million in 1949. Using its financial resources from a high demand for medical services and a powerful position as the gatekeepers to pharmaceutical companies, the AMA amplified Cold War fears of communism. From the testimony of Robert Taft to Congress that health insurance was the “most socialistic measure the congress has had before it” to the famed pamphlet that claimed Lenin felt health care to be the keystone of the socialist state, the AMA’s ideas infected the debate and shifted public opinion to favor “voucher payments” for those on welfare and labor unions to negotiate health insurance as part of members’ contracts.19

This debate raged during a period of “cultural distortion” arising from fear, frustration, and great technological change chronicled as the Cold War, a term that was itself the work of public relations expertise. The AMA and others were able to play on what historian Stephen J. Whitfield calls an entirely disproportionate response to communism in the United States circa 1950. Party membership was only forty-three thousand or so within a population of 150 million, much less than in European countries such as Italy or France, yet many Americans expressed great fear about the threat of communism. To explain this seeming contradiction, Whitfield points to the sudden loss of American technological dominance after the Soviet detonation of an atomic bomb in September 1949, the eruption of war in Korea, and the fact that an atomic war of “massive retaliation” would mean the end of the United States as well as its enemies.

After World War II, many nations undertook a national health insurance plan that included hospitals. The United States was uncommon in choosing to subsidize construction without a health insurance plan. In the United Kingdom, Lord Nuffield (William Morris of Morris Motors) funded a hospital construction program with a charitable donation that he hoped would spawn a national program of hospitals outside London. Architect Richard Llewelyn-Davies worked for the Nuffield Foundation combining architectural and psychological insights into spare hospital designs inflected for the local population. Internationally, the World Health Organization saw postwar hospitals as more than just curing the sick. These buildings housed many functions: they trained new staff, provided public health education and epidemiological laboratories, and could form a coordinated system of regional hospitals to make efficient use of specialists.20 The World Health Organization advocated standardization of information management, rules, and hierarchy based on the wartime models. Small rural hospitals were implicitly and explicitly tasked with attending to, educating, and managing the mental and physical health of the local populations in the rural UK, developing countries, or the rural United States. Architect Llewelyn-Davies encouraged designers to remember “that for most people a visit to a hospital is a frightening experience, and an atmosphere of reassurance and an absence of formality should, so far as possible, be the aim.”21

By 1950 the fight for national health insurance in the United States was over, and the poor got vouchers, veterans fought for government care, the wealthy paid for private insurance, and labor unions negotiated for the rest of the population in a mood of optimism for American capitalism and postwar affluence. The welfare state remained divided between public and private efforts, but Truman did manage to pass a major healthcare bill that included a subsidy for hospital construction. Americans came to associate government health insurance with mediocre health care, but government-subsidized buildings within a federally surveyed and accredited network did...