eBook - ePub

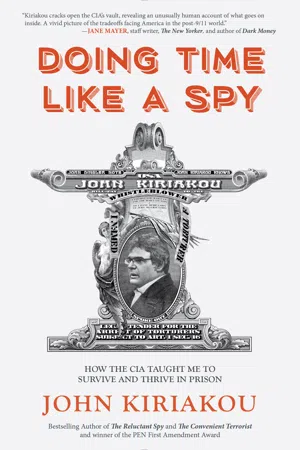

Doing Time Like A Spy

How the CIA Taught Me to Survive and Thrive in Prison

John Kiriakou

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Doing Time Like A Spy

How the CIA Taught Me to Survive and Thrive in Prison

John Kiriakou

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

On February 28, 2013, after pleading guilty to violating the Intelligence Identities Protection Act, John Kiriakou began serving a thirty month prison sentence. His crime: blowing the whistle on the CIA's use of torture on Al Qaeda prisoners. Doing Time Like A Spy is Kiriakou's memoir of his twenty-three months in prison. Using twenty life skills he learned in CIA operational training, he was able to keep himself safe and at the top of the prison social heap. Including his award-winning blog series "Letters from Loretto, " Doing Time Like a Spy is at once a searing journal of daily prison life and an alternately funny and heartbreaking commentary on the federal prison system.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Doing Time Like A Spy un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Doing Time Like A Spy de John Kiriakou en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Scienze sociali y Biografie nell'ambito delle scienze sociali. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

Scienze socialiDay 1:

“This Has to be Some Kind

of Mistake”

“This Has to be Some Kind

of Mistake”

On the morning of February 28, 2013, Jesselyn Radack, Tom Drake, Jim Spione, my cousin Mark Kiriakou, and his son-in-law Matt McCarthy drove me to prison in Loretto, Pennsylvania, to drop me off. When we pulled into the parking lot and I saw the big blue water tank, the double fences with concertina wire, and the roving guard vehicles, I said, “Holy shit! This is a real prison!” I was thankful that I was assigned to the minimum-security work camp on the other side of the parking lot.

I walked through the front door and announced to the first guard I saw that I was John Kiriakou and I was there to turn myself in. I got to the prison at 10:30 a.m. Because the judge and prosecutors both recommended that I serve my time in the minimum-security Federal Work Camp at Loretto, that’s where I went when we pulled into the parking lot. A CO there told me that all self-surrendering inmates had to go across the street to the Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) low-security prison to check in first. I went there, said I was there to self-surrender, and said goodbye to my family and friends. A CO then had me go through a metal detector. So far so good. I had brought nothing but the clothes on my back and a driver’s license.

The CO asked if I was ready. “I am,” I said, although I wasn’t quite sure what he meant. We walked out of the main entrance, turned right, and began walking around the building to the back of the prison, away from the camp. “Wait a minute,” I said. “I think there’s been a mistake. I’m supposed to be in the camp.”

“Not according to my paperwork,” he said. “Welcome to prison.”

I told myself to stay calm. You can call the attorneys on Monday and get this worked out, I thought. In the outbuilding at the back of the prison I went through a more rigorous body check and a more sensitive metal detector. From there, the CO escorted me to Receiving & Discharge (R&D) inside the main prison building. I was strip-searched again, given a cursory medical exam, my fourth DNA swab, and a set of khaki XXXXL pants and shirt (which for the next three days I had to use one hand to hold up—“sorry, but that’s the only size we have”), a pair of blue canvas slippers, a pair of underwear, a pair of socks, and a roll of toilet paper. The CO took a mug shot photo for my ID, and put me in a holding cell for forty-five minutes. My new first name was “inmate.” I was also now known as prisoner number 79637-083.

A second CO finally arrived and took me to my housing unit, Central 1, trying to be helpful along the way by saying things like “You only have thirty months? That’s good. A lot of guys die here because their sentences are so long.” He offered one word of advice: “If anybody comes into your room without being invited, that’s an act of aggression.” Great, I thought. I’ve been here for forty-five minutes and I’m going to get my ass kicked. He pointed out the hall I needed to take to get to the cafeteria and said that I would probably have an easy time of things.

We arrived in an overcrowded cubicle with three bunk beds. He pointed at a top bunk, said “home sweet home,” and walked away. I didn’t really know what to do at that point, so I climbed up into the bed and fell asleep. The truth was that I was in shock. I figured I would get my bearings when I woke up. I would introduce myself to my cellmates, generally keep my mouth shut, and figure out the lay of the land.

Two hours later I awoke and introduced myself to my cellmates: three Mexican drug smugglers, one of whom was a major prison gang leader, a black drug dealer from Virginia, and a Chinese drug dealer who, despite having been in American prisons since 1988, could barely speak a word of English besides “muthafucka.”

Soon after awakening, I was sitting in a chair next to my bunk when two neo-Nazis walked in. The first one, a tall, pale skinhead, had a swastika tattoo that took up his entire neck. The other was small and fat, with a swastika and “WHITE POWER” tattooed on his arms, along with a small skull on his left cheek.

I jumped out of the chair and put up my dukes. “What do you want?” I shouted.

“Take it easy,” the big guy said. “Are you the new guy?”

I kept my fists up. “Yeah. So?” The big guy leaned in.

“Are you a fag?”

“No,” I responded.

“Are you a rat?”

“No. I didn’t have anybody else in my case.”

“Are you a chomo?” I had never heard the term before.

“I don’t know what that means,” I told him.

“Cho-mo,” he said slowly, like I was stupid. “Child molester.”

“Of course I’m not a child molester,” I said, outraged.

“OK,” he continued. “You can sit with us at the Aryan table in the cafeteria.” Great, I thought. I guess now I’m with the Aryans.

Some time later I was sitting in the chair again when two hugely-built African-Americans wearing skullcaps walked into the room. I recognized them immediately as members of the Nation of Islam. The first one was holding a newspaper. Again I jumped up. Again I heard, “Take it easy. Are you the dude from the CIA?”

“I am,” I said warily.

He handed me the newspaper. “Reverend Farrakhan says you’re a hero of the Muslim people. We want you to know you won’t have any problems with us.” I thanked them and they went on their way. We never spoke to each other again.

(About a year later, after I had struck up a friendship with a senior captain from one of New York’s five organized crime families, the captain stopped me in the hall. “Let me ask you a question. Why in the world do you sit with those Nazi retards in the cafeteria?” I shrugged. “I don’t know. On my first day they said I should sit with them.” He looked at me like I was the one with a mental handicap. He put his finger in the air dramatically. “From today…you’re with the Italians!” And from that day I sat with the Italians. I attended every Italian party and dinner, we exercised together in the yard, and we became good friends.)

I had missed lunch and the laundry work hours that first day, so I didn’t eat and I had to wait until Monday for real clothes. I sat in my cell for two hours before Robert Vernon, an Australian arsonist, approached me. He’s the Australian I mentioned earlier. I’ll get into more detail about Robert in coming chapters. Suffice it to say that Robert makes a very good first impression. He’s warm, friendly, outgoing, and helpful. He mentioned that I would have to meet Dave Phillips, with whom Robert said I had “a lot in common,” Frank Russo, and Art Rachel. He would introduce me to them. He also said I needed to find a job immediately, or I’d be placed in the kitchen, the worst job in the prison. I was very grateful for Robert’s help in those first few days. For all his faults I would soon learn about, he helped me a lot.

As I said, I “self-surrendered” to prison. That is, I literally drove up to the prison, walked in the front door, and said, “Hi. I’m John Kiriakou. I’m here to turn myself in.” Being brought into the actual prison confused me because the prosecutors in my case, my attorneys, and the judge all agreed that I would go to a minimum-security federal work camp. Camps have no fences, no barbed wire, and some prisoners even work in town at the local university.

As it turns out, judges can only make recommendations as to prison assignments. The Bureau of Prisons, in its infinite wisdom, decided that I should do my sentence in a real prison. No club fed for me. This was going to be hard time. I finally got telephone privileges five days after I arrived. My first call was to my attorney to tell him that the Justice Department had put me in the actual prison, not the minimum-security work camp. “Oh, my,” he said. “Well, we can file a motion asking the judge to move you. But it’ll be two years before we even get a hearing, and you’ll be home by then. I’m sorry. You’re just going to have to tough it out.”

I understood immediately that I would have to “adapt to my current environment,” as the CIA had taught me. I took the first days and weeks to get the lay of the land.

No two prisoners’ experiences are the same. Certainly, prisons vary from location to location within the same security level. For example, Loretto has a reputation as being a haven for pedophiles. They walk freely around the yard, hang out in the TV rooms without being bothered, and generally carry on as if they own the place. In other low-security prisons, pedophiles are frequently banned from the TV room and have to stand in the hallway to watch TV, they’re subject to an occasional “thumping” in the yard, or they’re banned from the yard altogether. Many are not even allowed by their roommates in their own rooms except to sleep and during count times. There are no pedophiles in medium-security prisons or in penitentiaries because it’s too dangerous for them, unless, of course, they killed the children they molested, in which case they spend their sentences in a medium-security prison’s solitary confinement unit.

Low-security prisons have double fences topped with concertina wire, motion detectors, and roving patrols. But there are no guard towers in lows, and none of the COs are armed. There is very little violence other than the occasional fisticuffs over what show to watch on TV. Sexual violence is even more rare. I was surprised to learn that there is “situational homosexuality,” which is consensual (and still illegal), but that, too, is unusual.

I never served in a medium or a pen. Violence is a way of life in those institutions; serious, injury-inducing fights are routine occurrences, and prisoner movements are tightly controlled. The day before I arrived at Loretto a CO was murdered at the nearby US Penitentiary Canaan. The rumor was that he had mocked an inmate and took a shank to the heart. I lost count of the number of times fellow prisoners who had worked their way down from a higher-security prison told me, following a tiff with a CO, “If this were a medium or a pen, I would have cut his head off.” That kind of violence simply doesn’t happen in a low.

With that said, prisoner movement in lows is also pretty tightly controlled. Prisoners can only go from Point A to Point B during “ten-minute moves.” Once the ten minutes have passed, you’re locked down wherever you happen to be. If you want to go somewhere else, you have to wait fifty minutes.

The daily schedule is set in stone. Breakfast is at 6:00 a.m. and “work call,” where everybody heads out to do their “jobs,” is at 7:30 a.m. “Recall,” where everybody must return to their respective housing units, is at 10:20 a.m. Lunch is at 11:00 am, and then afternoon work call is at 12:20 p.m. Afternoon recall is at 3:00 p.m. Dinner is at 5:00 p.m. Evening work call is at 6:00 p.m., and final recall is at 9:00 p.m. That’s also when all prisoners are locked down for the night. “Lights out” is at 11:00 p.m. The only change on weekends and holidays is that breakfast is at 7:00 a.m. and there’s no work call.

Interspersed throughout the day (and night) are “counts.” “Standing counts,” where all prisoners must stand silently next to their bunks and be counted to ensure that nobody has escaped, are at 4:15 p.m. and 9:30 p.m. There is also a standing count at 10:00 a.m on weekends and holidays. Non-standing counts are at midnight, 3:00 a.m., and 5:00 a.m. Since most everybody is asleep at these times, COs go from bed to bed shining a ridiculously bright flashlight in your face, again to make sure that you haven’t escaped. I never really understood that, as we’d been locked in since 9:00 p.m., and it’s impossible to get through concrete, steel bars, and bulletproof glass, over two twelve-foot fences topped with concertina wire, past the night-vision security cameras and motion detectors, and into the night. But that’s just the way it is. I had a lot to learn in those first days. There is no “orientation.” You just have to pick things up on your own. It’s all part of a broader “prison culture,” where nobody is expected to help anybody else. I had to remind myself to keep quiet, watch my back, and try to elicit the information I needed.

There are no “cells” in the common sense of the word in low-security prisons. Instead, there are different housing setups depending on the unit in which one lives. Loretto was originally built as a Catholic monastery, and the original housing unit, North Unit, was made up of individual rooms with a closet and a small sink. When Loretto became a prison, the walls dividing each pair of rooms were knocked out, so one-man rooms became two-man rooms. Unfortunately, because of overcrowding, those two-man rooms now hold six men in bunk beds.

South Unit had smaller rooms, meant for two men, which when I was there held four or six. Larger rooms, whi...

Índice

- Introduction

- How Could This Happen?

- Day 1:“This Has to be Some Kind of Mistake”

- Welcome to Prison

- Rules to Live By

- Friends, Enemies, and the Weirdos and Lunatics In-between

- An Open Letter to Edward Snowden

- The Big Challenge, Part I

- The Stress of a Hostile System

- The Big Challenge, Part II

- The Threats Begin

- BOP Breaks a Promise

- Nothing is “Corrected”

- Prison Chapel

- Retaliation

- Prison Sentencing Reform

- The Big Challenge, Part III

- Marked as Dangerous

- Wrong Medication

- Roommates, or, The Road to Hell is Paved with Good Intentions

- Prison Health Care, Mental Health, and Suicide

- A Day in the Life: Vignettes

- The Council of Europe Takes an Interest

- Farewell from Loretto

- Letter to Loretto

- Acknowledgments

Estilos de citas para Doing Time Like A Spy

APA 6 Citation

Kiriakou, J. (2017). Doing Time Like A Spy ([edition unavailable]). Rare Bird Books. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3226345/doing-time-like-a-spy-how-the-cia-taught-me-to-survive-and-thrive-in-prison-pdf (Original work published 2017)

Chicago Citation

Kiriakou, John. (2017) 2017. Doing Time Like A Spy. [Edition unavailable]. Rare Bird Books. https://www.perlego.com/book/3226345/doing-time-like-a-spy-how-the-cia-taught-me-to-survive-and-thrive-in-prison-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Kiriakou, J. (2017) Doing Time Like A Spy. [edition unavailable]. Rare Bird Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3226345/doing-time-like-a-spy-how-the-cia-taught-me-to-survive-and-thrive-in-prison-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Kiriakou, John. Doing Time Like A Spy. [edition unavailable]. Rare Bird Books, 2017. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.