![]()

CHAPTER 1

Son of David

Before the 1990s, some scholars doubted the existence of David and Solomon as historical figures. This changed with the 1993 discovery of the Tel Dan inscription and André Lemaire’s 1994 reading bêtdāwīd on the Mesha Stela (see below). Today few would deny that the “house of David,” the royal Judahite dynasty, was indeed founded by David. For good reasons, however, biblical scholars and archaeologists have doubted the historical accuracy of the biblical stories of David and Solomon, stories that received their literary form at a later stage.

As of today, no scholarly consensus has been reached on statehood in tenth-century Israel and Judah. From archaeology, one can clearly identify ninth-century markers of statehood in Israel to the north and Judah to the south. Adding to this, during the last few years a growing number of archaeologists have pointed to such markers also in tenth-century Judah.

Was There a Judahite or United Kingdom in the Tenth Century?

Was there a “united kingdom” under David and Solomon—a kingdom that encompassed the Israel tribes to the north and Judah to the south? Or is this concept an idealized construction invented by later scribes connected to the royal Judahite echelon? On this, scholars disagree.

Davidic and messianic texts in the Bible point to David and Solomon as their foundation. The contents and profile of the son of David texts remain, even if the nature and extent of the Davidic and Solomonic state remain in the dark. But can elements of this theology be traced back to these two kings as historical figures or to their being in close memory? Can we find markers of statehood in Judea to the south or the central highlands to the north? Further, can a historical kernel in the David traditions be acknowledged? Can we identify Israelite settlements in Judah and Benjamin in this early period? Subsequent to a discussion of these issues, a short survey of the continued history of the kingdom of Judah provides the background for the ideological development of the David and son of David traditions.

Early Archaeological Markers

Khirbet Qeiyafa

Since 2007 archaeologists have unearthed the fortified village of Khirbet Qeiyafa in the Elah Valley, 32 km southwest of Jerusalem. This stronghold marked the border of some kind of early Israelite state, facing the large Philistine city of Gath. According to the excavator Yosef Garfinkel, C14 analysis indicates that the site was built slightly before 1000 and destroyed around 980–970.

Cultural markers point to Judahite inhabitants, not to the northern tribal entity of the highlands. The town was organized within a massive circular casemate wall with a width of 4 m (a casemate wall is a double wall divided into room sections, often with houses attached to the wall on the inside). Agricultural products were stored in pottery jars, with marks on their handles typical of Judahite administration and tax collection (Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2016, 10–28; Garfinkel 2017, 2020). Including a governor residence or palace and large storehouses, Qeiyafa must have been planned and built by a joint Judahite body, some kind of a state. The risky location, ca. 9 km from hostile Gath, would only be chosen by a territorial entity for strategic reasons.

Qeiyafa may be the strongest indication of the beginnings of a Judahite state—in the late eleventh or early tenth century. David is the obvious candidate for heading such a state: “In the summer of 2013, a central palace structure dated to the time of King David was discovered at Khirbet Qeiyafa. The structure stands in a prominent location at the top of the site, its area is about a thousand square meters, and the thickness of its walls shows that it stood several stories high…. If an outlying city on the western edge of the Kingdom of Judah contained such a structure, it is all the more likely that the kingdom’s capital, Jerusalem, contained no less impressive structures” (Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2016, 99).

At Qeiyafa, the archaeologists unearthed three aniconic cult rooms. The first contained two standing stones, a basalt altar, a limestone basin, and a libation vessel. In the third were found two artifacts characterized by Garfinkel as temple models, one in stone and another in pottery. Each artifact may be understood as a miniature temple entrance, located within a frame with three recesses. Garfinkel compares these recessed frames with ancient entrances to temples and tombs as well as details in the description of Solomon’s Temple in 1 Kgs 7:4–5 (Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2016, 28–60, 80–84, 99): “The Khirbet Qeiyafa stone model … shows that the biblical text, ‘And there were three rows of sequfim, facing each other three times’ should be understood as an elaborate entranceway decorated with triple recessed frames, in the typical style of entranceways in the ancient Near East” (Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2016, 82). For Garfinkel, these architectural parallels suggest that the biblical tradition of a tenth-century temple in Jerusalem indeed reflects historical memory.

Qeiyafa must have been a thorn in the eye of Philistine Gath, the largest city around. The Philistines did not tolerate its existence for long. After its downfall, the Judahites built Beth-shemesh 10 km northeast from Gath (Bunimovitz and Lederman 2017, 30–34) and, slightly later, Tel Burna to its south (Shai 2017).

Two fragmentary inscriptions were found in Qeiyafa; the larger contained five lines. Another tenth-century inscription was unearthed in Beth-shemesh, and one in Jerusalem—all written in early alphabetic script, the immediate ancestor of the Old Hebrew script. Bureaucratic or literary Biblical Hebrew is still not there, but not far away.

Jerusalem

What about Jerusalem, which according to biblical texts became David’s capital? In the City of David, boulders from a monumental tenth-century building have been unearthed immediately west of the “stepped-stone-structure” that slopes down toward the Kedron Valley. The stepped-stone-structure was constructed in a continuous process during the late eleventh and early tenth centuries. According to Mazar (2010, 34–46), the combination of the stepped-stone-structure and the monumental building was either the fortress of Zion that David captured (2 Sam 5:7) or David’s palace. For other scholars, the monumental building may be dated to any time during the tenth century and could be either Davidic or Solomonic. At least by the time of Solomon, tenth-century Jerusalem was a town with a monumental citadel. Pottery from Iron Age IIA shows that the town soon expanded to the Ophel ridge north of the City of David, with the establishment of a large administrative quarter.

To the north of Jerusalem, numerous new rural settlements were founded in the Benjamin plain in the eleventh century, and most of the older sites were still settled. For Sergi (2017, 4–8; 2020, 63), the stepped structure and the citadel constituted a power symbol of the Jerusalem king vis-à-vis these settlements, settlements that likely had to provide manpower to build this structure. The citadel demonstrated the existence of the newly born Jerusalem kingdom, soon to be known as the “house of David.”

In the second half of the tenth century, many Benjaminite sites to the north were abandoned, while Mizpah experienced growth and stood out as the main site of the northern Benjamin plain. This process shows northern Benjamin as a border region between two emerging kingdoms: Judah to the south and Ephraim/Israel to the north. The settlements of southern Benjamin were clearly allied with Jerusalem (Sergi 2017, 8–12).

Other Sites

According to 2 Chr 11:5–10, Solomon’s son Rehoboam fortified fifteen towns in Judea and Benjamin, Lachish being one of them. A fortified city wall was recently unearthed in Lachish, demonstrating that Lachish indeed was fortified for the first time in the late tenth century (Garfinkel 2020; Mazar 2020, 148). Tenth-century Israelite settlements have further been identified at Arad, Beer-sheba, Gezer, Tel Harasim, and Tel Zayit (Tappy 2017, 164–70). Then there are settlements going through a transition from Canaanite to Judahite (Gezer, Beth-shemesh, Tel ‘Eton, Tel Beit-mirsim, Tel Halif), and some Judean settlements that were established in either the late tenth or early ninth century (e.g., Tel Burna). Whether the tenth-century settlement at Mozah, 6 km west of Jerusalem, was established by Judeans so far remains an open question (Kisilevitz and Lipschits 2020; see p. 44).

The excavators of En Hazeva, biblical Tamar in the Negev, have identified a small Judean fortification tower from the tenth century, built over by a small fortress in the ninth or eighth century, which again was covered up by a larger fortress in the seventh century.

Summing up, archaeological evidence from Jerusalem, Qeiyafa, and sites such as Beth-shemesh, Lachish, Gezer, Tel Zayit, Arad, Beer-sheba, Tel ‘Eton, and Tamar shows the existence of a small Judean state throughout the tenth century (cf. Faust 2014, 11–34); the same is evinced by settlement patterns of the eleventh/tenth centuries around Jerusalem.

This survey of early Judahite settlements in the south doesn’t imply that all these settlers had an ethnic or tribal identity as belonging to “Judah.” In the eleventh and tenth centuries, the connotations of “Judah” might refer more to a region than to a clan-based tribal entity (cf. Lipschits 2020, 168). Judeans did not come from nowhere—there is some cultural continuity from Canaanite society to the early proto-Israelite villages many archaeologists identify in the highlands. Both in the north and the south, Canaanite towns and settlements could slowly acquire an Israelite identity—indeed, Ezekiel reminds his people that “your origin and your birth were in the land of the Canaanites” (16:3). At the same time, ceramic types from this period can be identified as Israelite, different from Philistine and Canaanite.

At the coast and in the lower Shephelah, there were Philistine cities and towns with a distinct identity. However, it remains an open question whether settlements further inland regarded themselves as “Canaanite,” “Judean,” or “allied with Ekron or Gath” during the eleventh and tenth centuries. Philistine pottery has been found at non-Philistine settlements in the Shephelah—trade and communication were crossing cultural borders. Settlements in the Shephelah may have been oscillating between Jerusalem and Philistia, where, in the tenth century, Gath replaced Ekron as the major Philistine center. With the development of the Judahite state throughout the ninth century, the connotations of “Judah” would soon signal ethnic identity, as evinced in the tribal blessings in Gen 49.

The development of Israelite polities in the tenth century can be compared with their neighbors to the east, where there are indications of emerging statehood in the eleventh/tenth centuries. The excavation of the copper mines at Faynan in the Arava Valley shows traces of an Edomite kingdom in the late eleventh and tenth centuries (cf. Gen 36:31: “the kings who reigned in Edom before any Israelite king reigned” [my translation]). At Khirbet en-Nahas, an early tenth-century monumental fortress measuring 70 m × 70 m has been unearthed, suggesting an organized political entity behind it. There was organized copper mining here from ca. 1300, run by the Edomite tribes themselves after the pullout of the Egyptian overlords around 1140, with development into large-scale industrial production in the tenth/ninth century (Levy, Najjar, and Ben-Yosef 2014a, 93–130, 231; Ben-Yosef et al. 2019). The copper installations at Timna, 105 km further south, used the same mining technology and belonged to the same political entity (Ben Yosef et al. 2012, 2019; Levy 2020). With Edomite tribes uniting into a regional polity, a similar effort among Israelite tribes would make sense.

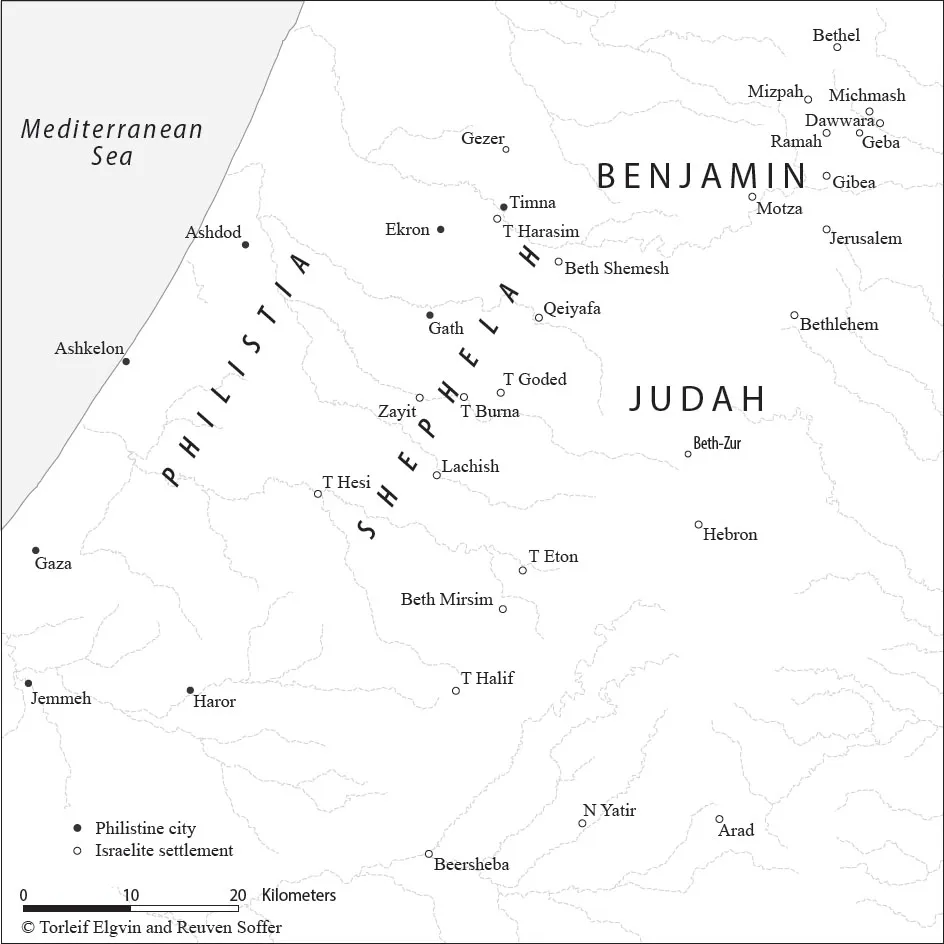

Figure 1. Philistine cities and southern Israelite settlements in the tenth and early ninth centuries.

Khirbet ed-Dawwara—a fortlike settlement established in the eleventh century and abandoned in the late tenth century.

Beth-zur—the 1957 excavations found a prosperous settlement in the twelfth/eleventh centuries and a substantial decline toward the end of the tenth century (Sellers 1958). Fortifications from Rehoboam’s time were not identified (cf. 2 Chr 11:7). A renewed growth in the ninth century could likely be explained by the developing Judahite kingdom.

Tel Burna—an existing Judean settlement fortified in the ninth century.

Tel ‘Eton, Tel Beth Mirsim, Tel Halif—Canaanite settlements that became Judahite around the late tenth century.

...