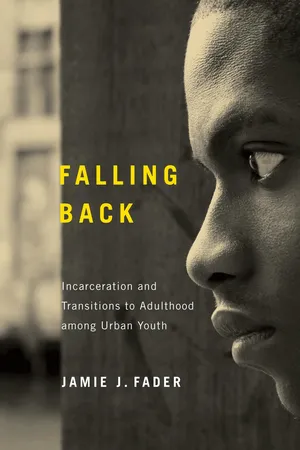

Chapter 1

No Love for the Brothers

Youth Incarceration and Reentry in Philadelphia

PHILADELPHIA IS OFTEN CALLED the city of brotherly love because its name combines the Greek terms philos, love, with adelphos, brother. For the twelve years I lived in the city, I found it exceptionally easy to strike up conversations at pubs, on buses and trains, and at dog parks. Urban sociologist Elijah Anderson has described places such as Rittenhouse Square and the Reading Terminal Market as “cosmopolitan canopies,” public spaces where people of different colors and social classes come together and interact with civility and even pleasure.1

The rest of the city, however, is deeply divided. Indeed, Philadelphia is one of the most persistently racially segregated municipalities in the nation. Although 43 percent of its residents are African American, middle-class whites and poor blacks rarely have more than superficial encounters. Most white residents have no reason to travel into Kensington in North Philadelphia, Kingsessing in Southwest Philadelphia, or Gray’s Ferry in South Philadelphia. Largely forgotten by everyone except the police, these and other impoverished neighborhoods belong to the “hidden Philadelphia,” an economically devastated and physically blighted urban area that contrasts sharply with the visible city. The young men whose lives I documented came from the hidden Philadelphia and returned to it after being released from Mountain Ridge Academy.

In this chapter, I introduce the young men whose stories unfold in this book and offer details about their lives before and after their incarceration. Their stories contradict Philadelphia’s depiction as a city that loves its residents. The inner city they inhabit is marked by poor public services, which are constantly under threat by budget crises; a rising murder rate; aggressive attempts by the police to curb drug sales; vanishing or absent job opportunities; old and deteriorating housing; failing schools; and increasing property taxes. Paradoxically, or perhaps because of these characteristics, Philadelphia has a state-of-the-art juvenile justice system, complete with a wide array of private correctional programs, an outcomes tracking system designed to help judges and program administrators improve services, and a system of reintegration that pairs probation officers and reintegration workers to support young people returning from reform schools.

Philadelphia’s residential landscape has been shaped by the clustering of racial-ethnic groups near the industries that employed them. As black migration from the South and immigration converged and precipitated white flight, African Americans found themselves in the “ghettos of last resort,” crumbling communities filled with abandoned houses and factories. In 1993 sociologists Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton identified Philadelphia as one of several cities where the white and black populations were “hyper-segregated.”2 An analysis using 2000 U.S. Census Bureau data demonstrated that Philadelphia ranks fourth in the level of residential segregation between blacks and whites and ninth in that between whites and Latinos.3

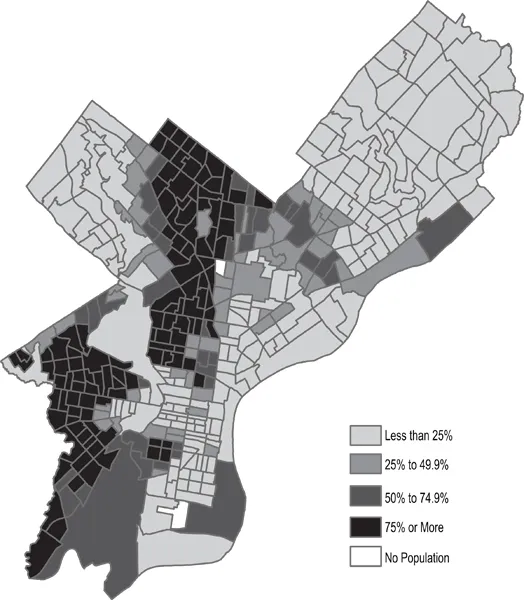

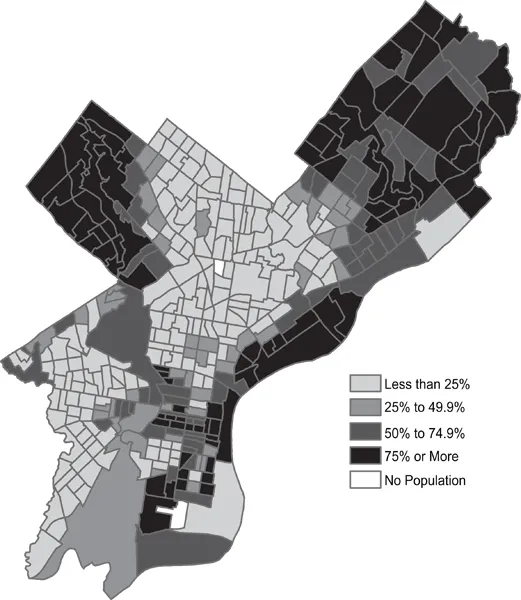

Figure 1.1 illustrates this point. The most heavily shaded census tracts, with 75 percent or more African American residents, are clustered primarily in North Philadelphia west of Broad Street, West Philadelphia from the western edges of the University of Pennsylvania’s campus to the city boundary at Sixty-ninth Street, and Southwest Philadelphia, with a small pocket in South Philadelphia, west of Broad Street and below Washington Avenue. As figure 1.2 shows, white Philadelphians are concentrated in Center City, Northeast Philadelphia, working-class neighborhoods on the Delaware River such as Fishtown and Port Richmond, and upper-middle-class communities in Northwest Philadelphia, such as Chestnut Hill. Many white neighborhoods are ethnically distinct, with Greeks and Italians concentrated in Fairmount (the Art Museum area), Italians in South Philadelphia, and Polish in Port Richmond, although this pattern is changing as these neighborhoods become gentrified.

Philadelphia’s recent history is best understood against the backdrop of strained relations between racial and ethnic groups competing for a declining number of jobs. Racial-ethnic tensions were exacerbated by patterns of immigration that are specific to Philadelphia. Because of its reliance on smaller-scale industries, Philadelphia never drew the massive waves of immigrants experienced by other similarly sized seaport cities such as Boston with firms producing durable goods. Between the restriction of immigration in 1924 and the lifting of these restrictions in 1965, the city’s composition shifted in three meaningful ways: southern blacks poured into the city, looking for work and improved living conditions; whites began fleeing to the surrounding suburbs; and the Puerto Rican population became established.4

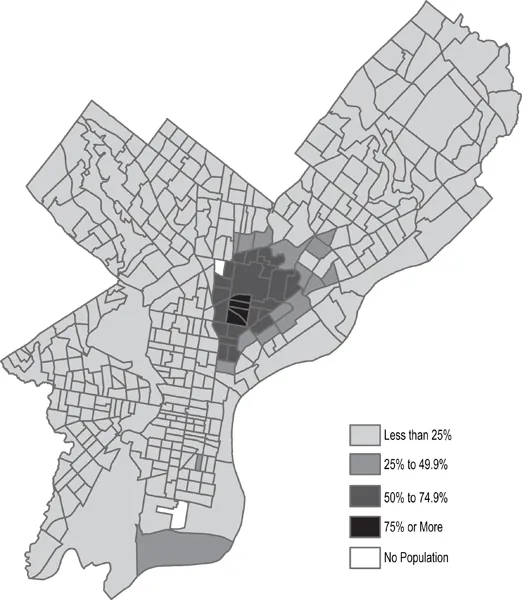

Immigrants arriving in Philadelphia in the 1980s and 1990s encountered a radically different economy from that of their predecessors. The city’s old industrial base had all but disappeared, and new immigrant groups—including not only Puerto Ricans, but also refugees from Southeast Asia and Koreans—had to compete with blacks for low-paying jobs in the service sector. Recently, the influx of Puerto Ricans has been surpassed by that of Central Americans, Mexicans, those from the Spanish-speaking Caribbean islands, and South Americans. African refugees from over thirty different countries have settled in the Southwest, West, and Northeast. Puerto Ricans have maintained a strong presence, despite their decreasing numbers in cities such as New York and Chicago.5 As is apparent in figure 1.3, Latinos, who are predominantly Puerto Rican, are concentrated in Kensington in North Philadelphia, east of Broad Street.

The young men whose stories I tell in this book lived in neighborhoods reflecting these patterns of racial segregation. Luis, who was Puerto Rican and white (but whose appearance suggested no hint of Latino), lived in the Frankford section of Northeast Philadelphia, a white working-class neighborhood.6 Sharif, Keandre, Hassan, Akeem, Raymond, Leo, and Isaiah were from North Philadelphia. Sincere lived in Kensington on a block inhabited by both African Americans and Puerto Ricans; his girlfriend, Marta, whom he moved in with shortly after his return from Mountain Ridge, was Puerto Rican. Warren and his cousin, Malik, resided in South Philadelphia, Warren in a gentrifying neighborhood not far from Center City and Malik in Gray’s Ferry. Eddie, James, and Gabe were from Southwest Philadelphia. Tony lived in West Philadelphia, not far from the campus of the University of Pennsylvania, where I attended classes.

During the course of my research, three young men moved to “better” neighborhoods, which were less racially concentrated and less scarred by violence. Shortly after coming home, Gabe moved to Upper Darby, an inner-ring suburb, with his girlfriend, Charmagne. Isaiah moved into a tidy single-family home in Northeast Philadelphia with his girlfriend, Tamika. He described how the neighborhood facilitated his efforts to fall back:

My neighborhood is quiet, a lot of Caucasians mixed with blacks. But it’s a quiet neighborhood, no violence, no gunshots. Well, there’s violence everywhere, but I don’t see any. I’ve lived here about two months now with my son’s mom. I see a lot of drug dealing going on, on the other side, where I catch the bus. I mean, I don’t feel safe but I know it’s not on my block so I feel safe that my son can’t go out there and just automatically get shot or something like that on my block, ’cause it’s not happening. I don’t know the drug dealers and they don’t know me and that’s how I keep it.

Sincere and his girlfriend, Marta, moved several times in the six years I knew them, mostly from one poor neighborhood to the next. Most recently, though, they moved to a spacious home in a community some people call “Port Fishington,” where Port Richmond, Fishtown, and Kensington come together. Although there are more African American residents on their block than the surrounding blocks, their neighborhood is safer, draws less police attention, and offers more amenities than their previous neighborhoods. Their new home is also a few short blocks from the Fishtown home I rented for my last three years in the city.

Sincere and Marta’s new address hints at a meaningful feature of the city: the proximity of living areas inhabited by the rich and the poor. Despite the pervasiveness of racial segregation, gentrification has brought the two groups together in adjacent communities, with clear but often renegotiated boundaries such as Girard Avenue in North Philadelphia or Washington Avenue in South Philadelphia. Watchful eyes and subtle or overt messages sent by white residents prevent poor blacks from patronizing stores and other businesses in white middle-class neighborhoods, and fear of violence prevents most whites from using public space in areas where African Americans shop and spend time. Two Philadelphias sit side by side.7

Straddling Two Philadelphias

Although I was not aware of it when I moved to the Brewerytown section of Philadelphia in 1997, I was part of a larger trend of movement by young urban professionals into the city. This reverse migration had been encouraged by the revitalization of several Center City neighborhoods such as Old City, Fitler Square, and the area near Graduate Hospital, as well as ten-year tax abatements for the construction of condominiums and lofts. According to the New York Times, by 2005 eight thousand new units had been built, with over half of the new residents benefiting from tax abatements having moved from outside the city.8 As middle-class suburban residents began returning to the city and buying condominium units for between $200,000 and $750,000 or even more, long-standing residents of neighborhoods such as Northern Liberties, Fishtown, Fairmount, and Pennsport began feeling the pinch of gentrification as they bore the brunt of property taxes.

Although I suspected early on that Paul and I were gentrifiers, we appeased our guilty consciences with the knowledge that our condo was not new and at least we were contributing to the tax base. Our townhome in Brewerytown, a neighborhood named for its abundant breweries in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was equal parts North Philadelphia and Art Museum area. We lived a block and a half south of Girard Avenue, a busy commercial strip with trolley tracks running down the middle and low-end stores such as Murray’s Meats, a dingy ThriftWay that closed soon after we moved in, Young’s Sneaker City, ACE Cash Express, and Thrifty Beauty Supply, which catered to the poor African American neighborhood just north of it—an area our next-door neighbor described as “death and destruction.” Most of the crime we experienced was aimed at property, including frequent rashes of car break-ins and vandalism, such as when my potted flowers were ripped up or when we returned home one day to find someone urinating on our doorstep. At night, in the distance, we regularly heard gunshots and saw police helicopters sweep their lights over our roof deck.

I had grown up in the suburbs of south Florida and had just moved from suburban Delaware, so our home in Brewerytown offered my first experience of straddling the two Philadelphias—white and black, rich and poor. Walking out my front door, I often encountered black men who were passing through on their route between the area above Girard and Center City. These men stepped with purpose, knowing that the Art Museum area was known for ethnic whites ready to defend their territory against invaders.9 In fact, during our first few months living there, a story circulated that a black man had been shot inside Krupa’s Pub around the corner because he had the “audacity” to ask for a drink. I never learned whether this story was true or if it was designed to deter nonregulars from entering the bar. From the roof deck of our townhome, on the other hand, we could see the Philadelphia Museum of Art, roof tiles sparkling in the sun like a Grecian temple; Boathouse Row was a short walk from there. It was the perfect spot to view the colossal Fourth of July fireworks show each year. Walking our dogs through the white section of the neighborhood, we passed Greek women sweeping their stoops and dressed all in black, other yuppies with dogs or jogging strollers, and expensive restaurants that drew diners from Center City.

In the mornings, I either hopped on the number 48 bus at the first white stop as the bus wended its way from North Philadelphia into the central business district or, in good weather, walked down the Ben Franklin Parkway to my job at Broad and Arch Streets. On my way, I passed the Youth Study Center (YSC), the detention center that held young people awaiting court hearings or placement in reform schools. Although I soon realized that inside the YSC was a crumbling way station of despair, the side abutting the Parkway featured two well-known public sculptures, Waldemar Raemisch’s The Great Mother and The Great Doctor, depicting adults offering care, comfort, and guidance to the children surrounding them.10 Next door, on Logan Circle, was Philadelphia Family Court, a beautiful but imposing neoclassical building designed as part of the local version of Paris’s Champs-Élysées. Between each set of Roman columns at the building’s entrance was a black wrought-iron gate, locked except for the sets nearest the front doors. Here probation officers, police officers, court administrators, and family members smoked cigarettes before entering the building. A line of people snaked out the front door and down the front steps as families of kids in trouble emptied their pockets, removed belts, and passed through a metal detector. In a second line on the other side of the entrance, lawyers, judges, and other court personnel were admitted with little scrutiny.

I spent time inside of Family Court with a team of program evaluators who were working with the city’s Division of Juvenile Justice Services, which was part of the Department of Human Services. During my first weeks on the job, several judges allowed me to sit in the jury box and observe the proceedings as part of my immersion course in the juvenile justice system. Our team met with judges and probation administrators to help them build the capacity to use the data we were generating. After I decided to return to graduate school and joined another research project there, I spent hours inside J Court, the specialized courtroom reserved for review and discharge hearings. Here, our research team was charged with identifying and meeting with young people who were slated to return from reform schools to Philadelphia public schools.

Later, when I set up my research project on young men returning from Mountain Ridge Academy, Family Court is where I first reconnected with them. The controlled chaos in the waiting rooms outside the courtrooms was a wonderful site for ethnographic research. The waiting rooms—like the courtrooms and the juvenile justice system as a whole—were filled with a disproportionate share of black and brown faces. Since these families were drawn from a small number of impoverished neighborhoods, they often saw old friends, got updates on each other’s lives, and passed the time by commiserating. They shared information about which judges were the harshest and which ones routinely started hearing cases an hour late. Parents usually waited for hours, afraid to leave for a short trip to the restroom or to grab a breakfast sandwich at the food truck parked outside lest their case be called and they lose their place in the queue or, worse, their child be held in contempt for failing to appear.

The waiting rooms at Family Court presented ample evidence of the massive structural changes affecting the urban economy, as well as the continuing history of racial conflict between residents and the police and the mayor’s aggressive, geographically based attack on drug markets. The young men I followed came of age during a time when jobs were scarcer than ever but the chances of being arrested for selling drugs were high. The rising rate of violence was concentrated in the hidden Philadelphia. Young men growing up in these neighborhoods were socialized into the street code as a means of survival. Understanding these conditions is essential for comprehending what it meant to these young men to be removed from their communities and incarcerated at Mountain Ridge Academy.

Philadelphia’s Social and Cultural Landscape

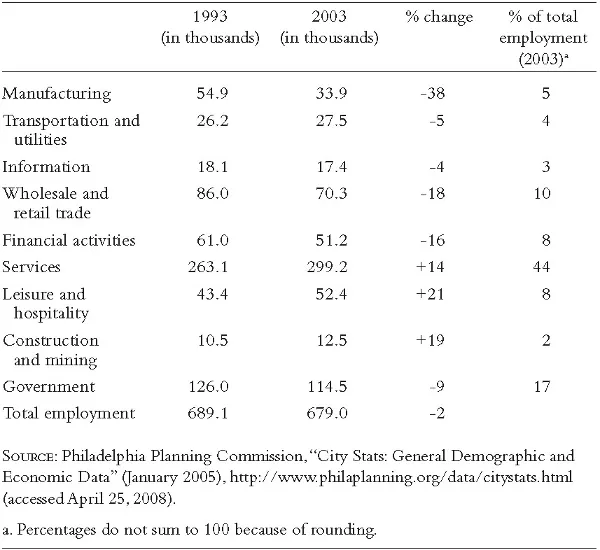

Like other urban areas that have been historically built on industry, Philadelphia has undergone a profound transformation as manufacturing plants have disappeared to the suburbs, the Sunbelt, Mexico, and overseas. The labor market is now sharply bifurcated, with well-paying positions for professional and technical workers and low-paying positions for less-educated workers.11 What makes the situation in Philadelphia worse than it is in other cities is the timing and duration of this transformation. Unlike its counterparts, Philadelphia never recovered from the Great Depression or prospered during the post-World War II period. Its vulnerability was rooted in its emphasis on nondurable goods, such as clothing, magazines, and cigars and cigarettes, whose machinery, plants, and equipment required less capital expenditure and were more easily moved to other locations than their investment-intensive counterparts producing durable goods, such as machinery and automobiles.12

Table 1-1 Changes in Employment Sectors for Philadelphia, 1993-2003

A defining ...