![]() Autism in the Family

Autism in the Family![]()

1

My Story

Everybody is a story ... It is the way the wisdom gets passed along.

Rachel Naomi Remen, Kitchen Table Wisdom

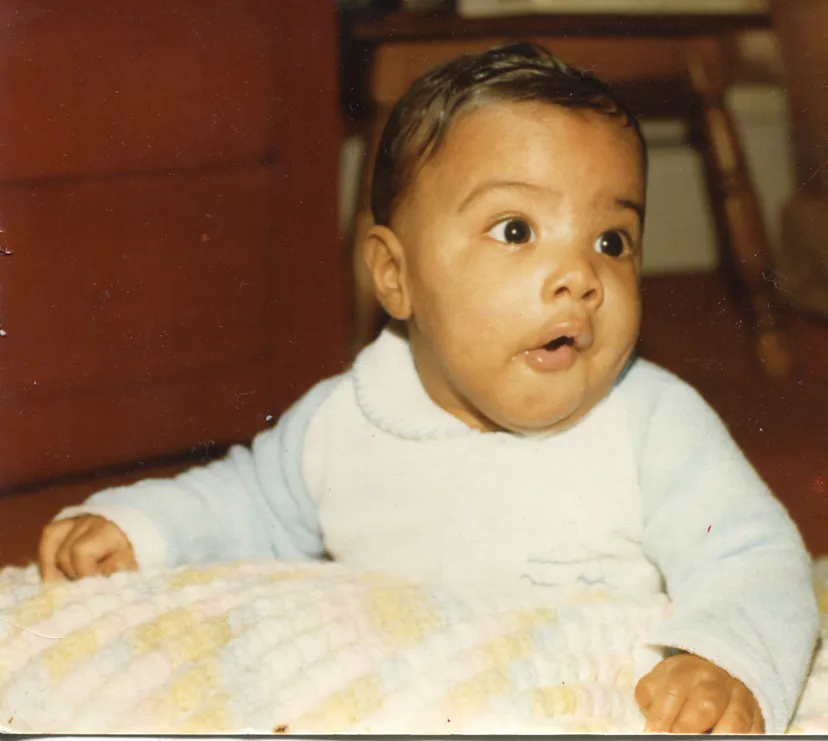

More than 30 years ago Tariq seemed perfect. He was all that I had imagined him to be, with something new to discover every day. At 4 months old, for example, he began to lift up his head and look around. I took a picture that I still prize because it bears an amazing resemblance to an old picture of me.

A month or so later he began to crawl. It was so much fun to see and feel his excitement. There was a gleam in his eye as he motored at will around the house. Now it was necessary to keep him safe, such as by steering him away from the steps or the fireplace.

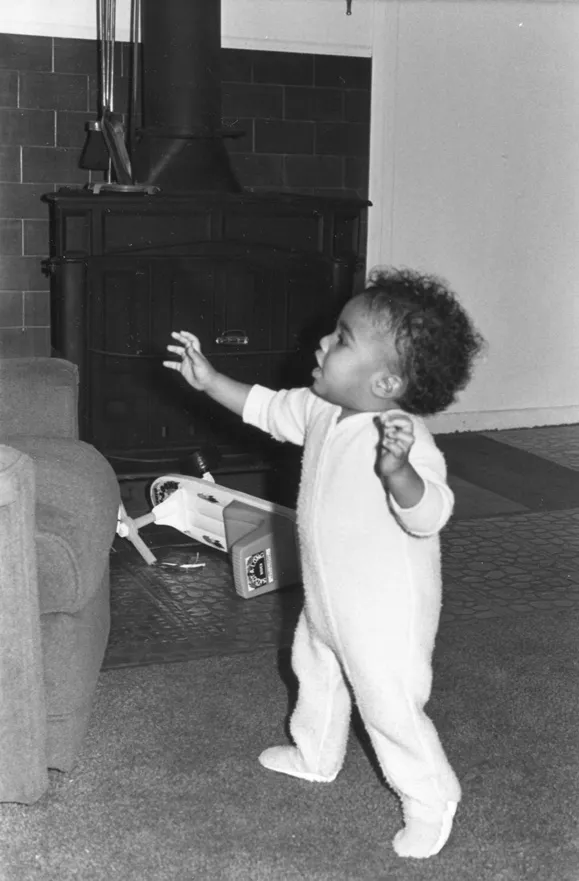

By his eighth month he could pull himself up to a standing position, beaming with pride. He would glance around smiling and planning his route to whatever looked like fun. A few weeks later he began to cruise, holding onto furniture and getting around upright whenever he could. I had fun holding his hands above his head and walking behind him.

Before long it was his first birthday, and his first baby steps came on that big day. I recall the look of apprehension and then the thrill of achievement on his face as he took those first awkward, wobbly steps. I was so proud of him. What an amazing accomplishment! I was cheering him on. I enjoy showing this photo of him at many of my public lectures.

Tariq raises his head for the first time.

Tariq takes his first steps on his birthday.

By 18 months he was just beginning to speak and had a small vocabulary. He had been meeting all of the developmental milestones. I imagined that before long he would play Little League baseball. I would beam with pride and cheer as he fielded a ball or swiftly ran the bases—a better version of me, who had played in right field from Little League through adult softball with limited skills. I would watch Tariq as my father had watched me. I imagined discussing social justice and sports with him as a young man. Our relationship would be close and warm. I would be patient when he needed or wanted it—a better version of my father.

At 18 months, in May 1981, Tariq was treated for an ear infection. By coincidence he was never the same again. He became frustrated and withdrawn. He cried a lot and did not sleep well at night. I worried, especially at night, when I was awake with him. My oldest daughter, who prefers privacy and does not want to be mentioned by name, had been born that same month. At first the pediatrician thought that Tariq could be having an emotional response to her birth. I hoped that the doctor was right, but I was scared.

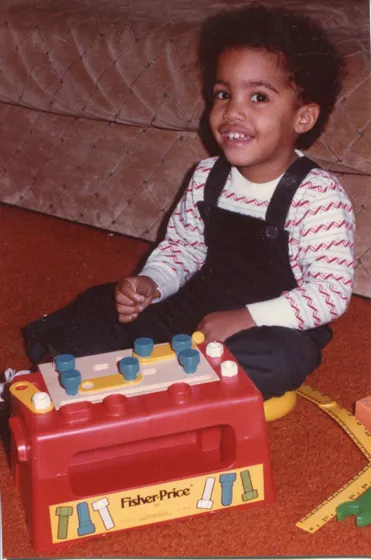

Tariq stopped talking and stopped playing with the toys he had received for his birthday—such as the little workbench with its nuts and bolts and tools. My parents had given it to him because it was just like one I had had as a little boy. He began playing with a transparent rattle with brightly colored beads inside. He seemed fascinated by this toy and played with it for hours while ignoring virtually everything else around him, including his newborn sister. This was the beginning of his falling in love with things and falling out of love with people. It would not be until years later at the 2011 Autism Society of America Conference, that I would finally come to learn how this process had been documented through the research of Ami Klin, Ph.D., and his team at the Yale Child Study Center (Klin, Warren, Schultz, Volkmar, & Cohen, 2002). Children later diagnosed with autism begin life focusing their gaze on people and gradually shift from faces to things during the early months of life.

Tariq plays with the workbench from my parents.

Meanwhile, when our daughter was born, I was thrilled. Life seemed complete, but that feeling did not last. I became tense and anxious, wondering if his mother or I had done anything to cause Tariq’s condition. I kept telling myself that everything would be okay.

A rude awakening was imminent. The excitement from new accomplishments was gone. My sweet toddler was gone. He became very agitated and upset if the rattle was taken away. His life, which had been a great joy, became a worry that preoccupied me. I was glad to see him when I got home from work, but the fun was gone. He still liked being touched and cuddled, but he turned his face away. He preferred the rattle. I longed for Tariq to look into my eyes and speak.

When he was 2, I spent the summer with Tariq while on vacation from my teaching job. The pediatrician had said that he might just need time. I worked to get his attention and establish eye contact. I would put him on the swing and stand in front of him as I pushed him. I tried to catch his gaze for a second. He would turn his eyes to the side. He was a master at avoiding all sorts of connection including eye contact.

It felt like a personal rejection. The situation was especially frustrating because I expected to be able to help him. At work, teaching remedial reading and writing in a support program, I could help college students with learning differences, but my efforts with my own son were fruitless. Eventually I learned to back off and make contact in different ways, but not until he was diagnosed with autism a few years later.

As his third birthday approached, it was clear that Tariq could not attend a typical preschool. His lack of speech indicated that he was far behind other children his age, but that fact was hard to face. His mom and I took him to a preschool that included children with special needs, but he did not even fit there because he could not sit still for more than a few seconds. The preschool’s consulting psychologist thought he might be hearing impaired, because he was not responding to his name. On his advice I toured a school for children with hearing impairments. My insides shook as I worried that my boy would be walking around with two hearing aids.

I wondered what his life would be like. He would just be different, I told myself—just different. There were trips to numerous specialists and special schools and many sleepless nights waiting for test results and no answers to the mystery of why Tariq had stopped speaking.

A specialist found fluid in his ears that was blocking his hearing, and he was treated with medication. There was hope for a simple solution. Tests of his brainstem indicated that his ears worked, but it was impossible to tell whether he comprehended words. The fluid cleared up, but he still expressed himself by grunting, babbling, and crying. He constantly twisted and turned to get away. At night, I dreamed that the babbling would turn into words again.

Tariq was in an early intervention program by his third birthday. In the early 1980s, early intervention began at age 3 as opposed to at birth. He was the most difficult child in the school to manage. He required one-to-one attention at all times. He could not stay in his seat for more than a few seconds if left unattended. Whenever possible, I spent the day with him, helping his teacher. I kept asking his speech therapist why she was just playing with him and why he was not talking. She gave me a pamphlet from the Autism Society of America with stick figures illustrating the signs and symptoms of autism. The words and illustrations were a blur that I could not read.

Eventually Tariq was diagnosed with a pervasive developmental disorder. In 1984 autism was diagnosed in 12 out of every 10,000 children (Gillberg, Steffenberg, & Schaumann, 1991). The team of professionals that evaluated him at the hospital where he had been born used the words autistic like and retarded in their diagnosis. I was first numb and then livid. They seemed to have no hope for my son. How could I give up? Their words sliced through me like a knife. My head throbbed, and I thought it was going to explode.

The social worker broke the news with, “Hasn’t anyone told you that your son is autistic?” What a way to tell a parent about autism!

I withdrew. It was painful to read that autism was a severely incapacitating and lifelong disability. It was hard to comprehend that my child’s brain was so impaired. I was told that communicating with others or the outside world would be extremely difficult for Tariq.

I couldn’t talk about it. I wanted to, but the words just stuck in my throat, especially the A word: autism. I couldn’t get it out. Once in a while I would blurt out my worry that my son still was not talking, even though he was older than age 3. At night I cried and cried. There was no comfort. Professionals, relatives, and friends rarely knew what to say.

Like many other parents, I spared no expense in the quest to find a cure. We tried alternative therapies, megavitamins, and a wheat-free diet. The burden of the debts from these and other treatments was a reminder of my dreams for Tariq’s recovery. My dreams died a slow death as I ran out of treatments to try. As I faced reality, I began to grasp that Tariq’s condition was permanent.

Unfortunately I felt the most alone at home. To put it simply and kindly, the strain of Tariq’s disability added to other stresses, which led to a divorce. After years of trying to go through it together, it was easier to try alone. As a single parent with joint custody, I faced a life that had changed permanently and profoundly—something I had not planned or allowed myself to imagine.

Vigilance was required every waking minute. Because Tariq rarely slept through the night, I was constantly exhausted. The sleep deprivation lasted for more than 7 years, and the feeling stayed in my body even longer. I never knew what would happen next. My son was in perpetual motion, and it was hard to know what you would find as you followed or chased him. The entire house had to be child-proofed. Even the refrigerator, drawers, and toilets had to be locked.

Because he knew no danger, there was a constant threat that Tariq would run into traffic, burn his hand, or step over the edge of the pool into the deep water. The only part of my dream for Tariq that came true was that he became a fast runner, but unfortunately this made for few relaxing moments for me.

Once he got out of my apartment in the middle of the night. I was terrified as I ran looking for him; my heart pounded so hard that I thought my chest would burst. I found him playing happily in the playground a few blocks and busy streets away, but my heart kept beating quickly. His death was the only thing that I could imagine being more difficult than his life with this diagnosis.

I decided to begin psychotherapy, and this helped me keep going. It was the best thing I could have done for myself. I came from a family that did not often express feelings, but this was a skill I needed now. My therapist helped me to express my feelings, but it was hard to make sense of them. I was being flooded and overwhelmed with emotion, and it felt crazy at times.

Why couldn’t I calm down? Professionals constantly emphasized doing more for Tariq, but this was not helping me ease my guilt or find acceptance. It felt like a defect in me was keeping me from accepting my son as he was. Was I a bad person? Why wasn’t love enough?

At that point, more than 25 years ago, my colleague and close friend Cindy showed me an article called “Handicapped Children and Their Families” in the then-current issue of the Journal of Counseling & Development. This article talked about the grief experienced by the parents of children with disabilities. It was written by Milton Seligman, Ph.D., of the University of Pittsburgh and also the parent of an adult child with a disability. As I read slowly, his article spoke to me.

Many disconnected feelings and thoughts began to make sense. When I completed the article, I leaned back in my desk chair; took a few slow, deep breaths; and realized, “So that is what Tariq’s life is all about for me: I am a bereaved parent.” I diagnosed myself with grief.

From that day onward, my life began to change for the better. I had a new lens through which to analyze my experience. This helped me learn to cope with the many problems that come with autism. It took time and help. I understood my thoughts and feelings better. In retrospect, I believe that at that time there was a general lack of support for parents of children with disabilities or understanding about the grief they experience. That lack still exists and motivates my professional work as a practicing psychologist, presenter, and author.

I struggled through some horribly dark moments, but I began to reclaim my life. The friend who showed me that article helped me by encouraging me to talk and by listening without judgment or expectation to everything I had to say. Cindy eventually became my girlfriend, and several years later we married. Life did indeed go on with new dreams.

I had entered a doctoral program in the Department of Psychological Studies in Education at Temple University before fully understanding that my son would have this disability for life. Because I was doing everything possible for Tariq, I knew in my heart that he would want me to pursue my own development. It was trying at times, but my professors and my boss at work were very supportive. There were things to look forward to once again—personally and professionally.

When my daughter learned to read, I was very thankful. Every time she learned a new word it let me know that her brain was normal. I cried tears of joy while observing her breaking the code and learning to read. It was unbelievably exciting to live through this period—not to mention a great relief that she could learn in the typical way.

I literally could breathe easier. Typical human development seemed like a miracle. My oldest daughter has a special talent in art and writing, and I was filled with pride and gratitude when she gave me a drawing or painting or showed me something she had written. I had learned that life is very fragile at times, and you never know when something might break your heart.

For my doctoral dissertation, I researched how families coped successfully with having a child with a disability. It was a way of focusing on resilience and finding balance. Besides my interest in knowing as much as possible for myself, I hoped that what I learned might be of use to others. I hoped to foster understanding and partnership between families and professionals.

This began happening after Tariq’s ninth birthday as I spoke to groups of parents and professionals. I became effective at helping people connect and collaborate. By this time, Tariq’s disability was so severe that he needed around-the-clock care and had to be placed in a residential program. This was the hardest decision I ever had to make, and one I explain in more depth in Chapter 13. In 1990, I was asked to help develop a training package for the New Jersey Department of Education to foster parent–professional collaboration.

Subsequently I became a full-time trainer for the New Jersey Department of Education. I got a lot of practice focusing on professional issues while drawing on my own life experience. I spoke to thousands of parents and professionals in preschool programs and at professional conferences. It was a way that I kept Tariq with me and derived meaning.

In 1991, the Journal of Counseling & Development published my article “Lost Dreams, New Hopes,” about my life experiences and their impact on my professional life. I got letters and telephone calls from people who read the article. It was extremely rewarding to hear from college professors who used it as a handout in counseling and special education classes.

That same year Cindy and I had our first child, Kara. A little more than 2 years later, in 1993, our daughter Zoë was born. Kara and Zoë’s development was a testament to the vitality of our relationship. In 1992, Cindy and I founded Alternative Choices, an independent psychology practice. Our practice grew to the point that I was able to leave my full-time position with the New Jersey Department of Education. I now specialize in working with the parents of children with autism and other special needs. Cindy and I have always been able to work our schedules around our family. It is a life that we enjoy together.

In addition, I have served as a consultant to schools and parent groups, including having been the consulting psychologist to a special 3-year Head Start project to increase the involvement of fathers and male role models in the lives of young children. Currently I work with families and lecture nationally and sometimes internationally. I make a living doing what I enjoy. It is a special treat, and one that I am proud of.

I have come a long way. My son’s disability helped me to develop more than I had ever imagined. He gave me the opportunity to do something special. The knowledge and wisdom that I acquired is still helping me to be all that I can.

Tariq has made me aware of the value of life. He is so innocent and generally happy. Tariq is such a gentle soul that he has always been a staff favorite wherever he has been. These thoughts alone bring me a calming stillness and a smile.

I now live a rewarding but different life. I keep learning as I help other families who are living with autism. Sometimes I’m not sure if I deserve such a full life. When I walk into an early intervention program or a consultation with the parent of a newly diagnosed child, I revisit my own experiences. As I look inside myself, the survivor’s guilt softens. I am reminded by their story that I deserve to feel good—for I have paid my dues.

My focus in this book is this lifelong process of taking care of everyone in the family after a diagnosis of autism. My goal is to integ...