![]()

1: On the Eve of the New Deal

The [Democratic Party] platform is a model of force, brevity and sincerity.... Declaring that the ’Only hope for improving present conditions ... lies in a drastic change in economic and government policies,” it urges that the nation turn back to the fundamental democratic doctrine of “Equal rights to all, special privileges to none.”

Atlanta Constitution, 1 July 1932

In this very state of confused despair and bitter disillusionment lay the seeds of a new racial attitude and leadership.

LESTER GRANGER, Opportunity, July 1934

In 1932, as the nation sank deeper into the depression, an official of the Hoover administration told Congress, “My sober and considered judgement is that.. . federal aid would be a disservice to the unem-ployed.”1 The promotion of self-reliance rang hollow, however, as the number of farm foreclosures multiplied and as people from all levels of society fattened the ranks of the unemployed. Even southern Democrats abandoned what had been an uncompromising opposition to federal intervention in southern affairs, the cardinal principle of post-Reconstruction state governments. As the presidential campaign approached, they pressed for government action and rallied behind the candidacy of the governor of New York, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The South’s retreat from a dogmatic adherence to states’ rights showed the region’s desperation. The Atlanta Constitution’s confident promotion of the Democratic Party as the guardian of “equal rights,” however, reflected the extent to which national and regional sensibilities regarding race and citizenship were one. Except for the Reconstruction period, the federal courts and the nation’s political institutions had accommodated the white supremacist order in the South. Woodrow Wilson, the last Democrat in the White House, had extended racial segregation to include all federal facilities in the nation’s capital.

Yet, as Lester Granger and other young black leaders anticipated, the political upheaval spawned by the depression created new opportunities for African Americans to assert their citizenship. Black voters in northern cities, fed by the wave of war-induced migration from the South, earned strategic positions among the urban coalitions that transformed the national political landscape during the 1930s. The great majority of black Americans, however, remained in the South, where they were barred from politics. But even there, the nationalizing trends and democratic activism surrounding the New Deal stirred efforts among the disfranchised to find a way out of what one contemporary called the “economic and political wilderness.”2

On the eve of the New Deal, Horace Mann Bond, a young black scholar and educator, explored the schizophrenic contours of southern life in an essay for Harper’s magazine. He began by noting the widely popular “cult of the South.” Here, “The white man is the Southerner, the Negro—well, a Negro.” Drawing on family memory and on his extensive travels throughout the region, Bond looked beneath this veneer and inquired into the nature of the South as a “geographical portion, a psychological entity.” He wove a textured portrait of black and white life and of the transparent boundaries of the caste system. “Customs, politics, society, all of the deeper and more extensive ramifications of culture,” Bond observed, “bear the imprint of those of us who, being Southerners, are also Negroes.”3

Regional identity, however, often failed to embrace the richness and complexity of southern life and culture. Bond explained that for whites and many blacks, the idea of the South was corrupted by the habitual celebration of a “white” South in which the Negro was a mere shadow “deepen[ing] the effect of the leading silhouette.” It was this South that captured the national imagination. Although it had no basis in material reality, it reflected a political reality whereby “the accolade of Southern citizenship, of participation in the fate of the region,” had been “appropriated by white persons.” When Bond wrote in 1931, amid widespread economic despair, the South’s deeply racialized civic life appeared to be unyielding, thus obstructing his effort to articulate a vision of the region’s future.4

Black exclusion was emblematic of the political order established at the turn of the century with the final triumph of the Democratic Party. In a relentless campaign of fraud and violence, Democrats had navigated the tumultuous electoral contests of the late nineteenth century under the mantra of white liberty and home rule, appealing to the white South’s abiding mistrust of politics and government. The contentious politics of the era crested with the Populist challenge of the 1890s, along with a growing movement to restrict the franchise. Democrats adroitly manipulated the economic unrest and anxieties that fed the Populist movement, pinning the region’s woes on the newly enfranchised black voters and promising their complete removal from public life. By the first decade of the twentieth century, suffrage restrictions were in place in all southern states, segregation laws penetrated every facet of southern life, and Democratic Party hegemony—or what North Carolina newspaperman Josephus Daniels hailed as “permanent good government by the Party of the white man″—had been secured.5

The South’s new order, which virtually nullified the constitutional amendments enacted during Reconstruction, won the approval of the Supreme Court and the sympathetic support of northern white sentiment. Reconciliation of northern and southern whites advanced on the battlefield of the Spanish-American War in 1898, a war that reinforced white racial arrogance. Meanwhile, the widely popular tenets of social Darwinism, offering “scientific” validation of Anglo-Saxon superiority, seasoned the politics of the Progressive Era. In the north, reformers blamed immigrants for labor turmoil and the corruption of urban politics and supported suffrage restrictions as essential to the smooth functioning of democracy. The history of Reconstruction, as it was written early in the twentieth century, offered a powerful lesson in the perils of enfranchising the ignorant and socially inferior. William A. Dunning and his graduate students at Columbia University provided scholarly legitimacy for the white South’s indictment of Reconstruction as a horrific time, a fatally flawed experiment. D. W. Griffith further popularized this view in his 1915 celluloid testimonial to sectional reconciliation and white supremacy, The Birth of a Nation.6

Having prevailed as the party of white solidarity and regional self-determination, the Democratic Party offered the South “a politics of balance, inertia and drift.” Disfranchisement barred many whites as well as virtually all blacks from the electoral process. The party represented a diverse range of potentially conflicting economic interests, from Black Belt planters to New South boosters, with all kinds of state variations. A type of negative politics, committed to maintaining the fundamental principles of the racial and economic status quo, provided some coherence. As historian Michael Perman has explained, in the state constitutional and legislative battles to “redeem” the South, the Democrats “saddled the region with a constricted governmental apparatus and a repressive system of land and labor” that doomed the region to decades of static and adaptive economic development.7

Federal endorsement of white hegemony had robbed black southerners of their last defenses against the usurpation of their civil and political rights. But traditions of freedom and citizenship, born in the crucible of Reconstruction, sustained communities of resistance. Black southerners developed an expansive vision of democracy in their efforts to secure the fruits of emancipation. The black church, as Elsa Barkley Brown has explained, was the site of mass meetings where the newly freed “enacted their understanding of democratic political discourse.” During the tumultuous decades of the 1880S and 1890s, black men and women met white terrorism at the polls with a group presence on election day. As an organized and articulate body of citizens, black communities throughout the region took an active part in Republican Party politics and explored alliances with independent groups such as the Farmers’ Alliance and the Populist Party. Indeed, the persistence and endurance of African Americans in an increasingly hostile political environment was used by proponents of disfranchisement to rally white support.8

By the dawn of the new century, government and politics had become “inaccessible and unaccountable to Americans who happened to be black.” African Americans continued to develop strategies for social and political development within a separate public sphere. This was dominated, in large part, by the church but also included fraternal organizations, the black press, and other institutions. Churches often focused the mobilization of community resources to provide educational and social welfare services, leadership training, and organizational networks. The church, notes Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, served as a vehicle of collective identity and empowerment and provided a place “to critique and contest America’s racial domination.”9

While the rudiments of citizenship expired, formative developments shaped possibilities for future change. Resistance to new laws segregating streetcars erupted in locally organized boycotts in at least twenty-five southern cities from 1900 to 1906. These failed to stem the tide of segregation, however, demonstrating the futility of such actions. Black leaders and intellectuals continued to debate a broad range of political thought and strategies, framed by the accommodationism of Booker T. Washington, the civil rights protests of Ida B. Wells, W. E. B. Du Bois, and others, and the legal activism of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909. Ideological divisions and tactical differences were enhanced by the daunting nature of the struggle, namely to sustain black communities amid the crushing environment of white racism while envisioning a way forward.10

Black migration, confined largely within the South, had been a vehicle of freedom, self-determination, and survival since the earliest days of emancipation. Starting in 1914, however, the “Great Migration” of the World War I era stimulated a steady and ultimately transforming movement of black southerners to the North. Black migration continued even after wartime demands ceased and jobs became scarce. The boll weevil and growing pressures of surplus labor pushed increasing numbers of blacks off the land during the twenties. Nearly one and a half million southern blacks went north from 1915 to 1929, an internal migration of vast proportions and significance. (At emancipation in 1863, the total population of freed blacks in the South has been estimated at four million.)11

The North hardly resembled “the promised land.” During the “Red summer” of 1919 racial violence erupted in riots in northern urban centers as well as in the South; the worst outbreak was in Chicago. But discrimination and segregation in northern cities lacked the relentless brutality seen in the southern system. In the North, blacks responded to white violence with a militancy that was refracted in the “New Negro” movement of the twenties, while the Garvey movement stirred mass demonstrations of racial pride. During the twenties, black communities in the North nurtured the outpouring of cultural, literary, and musical creativity that flowered in the Harlem Renaissance. And, in the North, black citizens had free access to the ballot. As their numbers increased, black participation in northern urban politics gradually became a factor of national consequence.12

For the great majority of blacks remaining in the South, however, industrialization and urbanization extended the grip of segregation. During the war and postwar years, mechanization and upward pressure on unskilled wage earners sharpened racial dualism within the southern labor market. Black jobs and white jobs, with few exceptions, became increasingly non-competing. Black men and women continued to dominate the tobacco industry, but white employees worked the machine-tended jobs in separate buildings. A similar trend of racial distinction emerged in the iron and steel industry, also dominated by blacks, who held both skilled and semiskilled positions. The textile industry had excluded blacks from the start; by the 1920s, its white workers were paid well above black wage earners. Unionization of skilled crafts increased during the 1920s, and these unions, such as the building trades, were among the most racially exclusive. In seeking to explain these developments, some historians have suggested that by the 1920s, black and white southerners were entering the work force with increasingly dissimilar educational backgrounds. But for most industrial jobs in the South, education bore little relevance to the job requirements. As historian Gavin Wright has explained, job classifications became primarily a function of caste and were “symptoms of the larger process of creating a segregated society.”13

Two women and a child standing in front of a shack and behind barbed wire, Alabama, 1936. (Photograph © Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum, City of Oakland; gift of Paul S. Taylor)

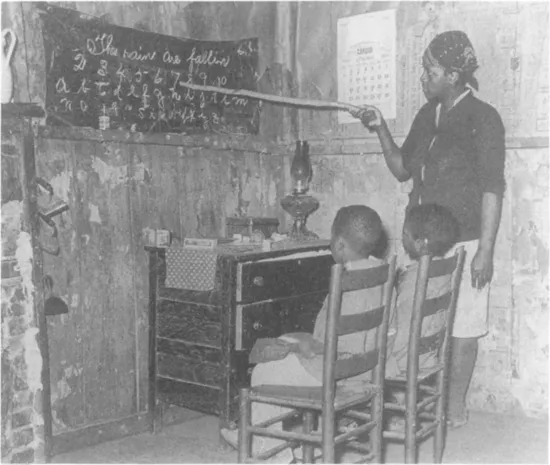

Children being schooled at home in Transylvania, Louisiana, 1939. (Photograph by Russell Lee; courtesy of the Louisiana Collection, State Library of Louisiana, Baton Rouge)

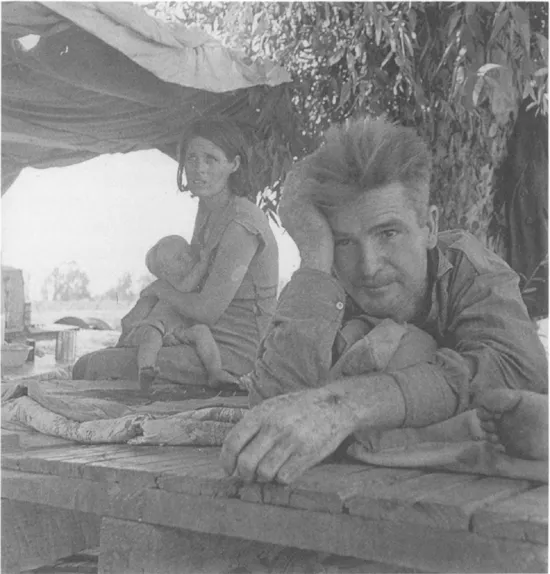

Drought refugees from Oklahoma in Blythe, California, 1936. (Photograph by Dorothea Lange; courtesy of the Library of Congress)

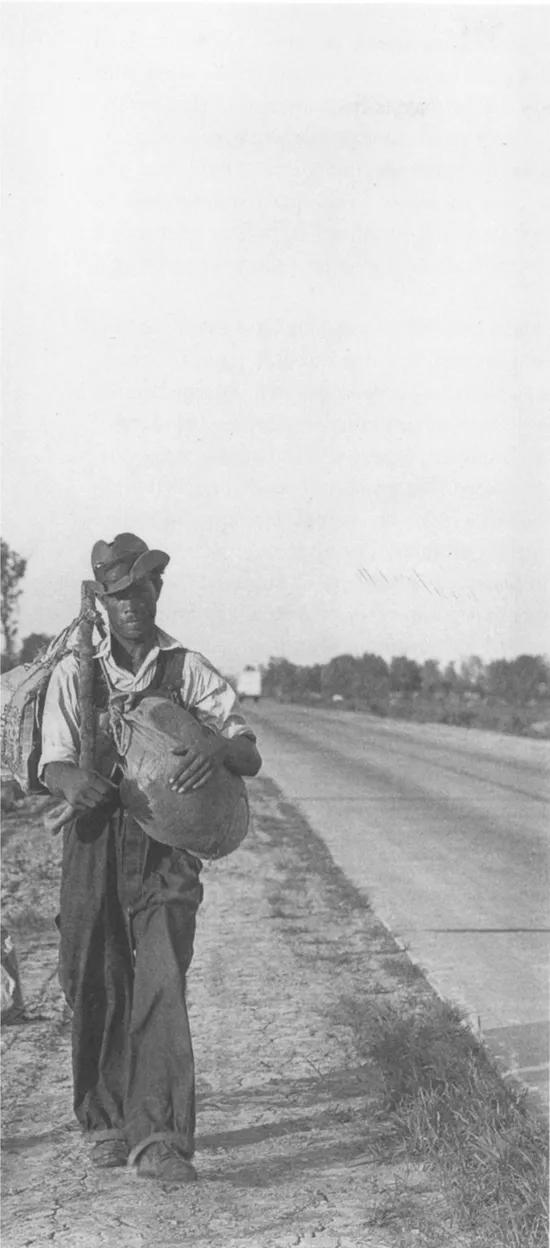

During the 1930s, writers and government investigators “discovered” a South that had been largely beyond national consciousness. Images of the region’s impoverishment were captured by photographers for the New Deal’s Resettlement Administration/ Farm Security Administration.

“Damned if we’ll work for what they pay folks hereabouts.” Migrants on the road, Crittendon County, Arkansas, 1936. (Photograph by Carl Mydans; courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Southern industrialists proudly presided over an abundant supply of “native” white labor—"thrifty, industrious, and one hundred percent American.” They advertised a cheap and inexhaustible supply of nonunion labor as the region’s greatest resource. A flurry of union activity among segments of the textile, mining, and tobacco industries met severe postwar wage cutbacks in 1919, but it quickly dissipated. Ten years later, worker opposition to the stretch-out system in the textile industry erupted in a series of strikes and unionization activities in the Carolinas. The most notorious and least typical confrontation came in Gastonia, where the Communist Party embarked on its preliminary effort to promote class struggle in the South. But Gastonia provided a lightning rod for antiunion sentiment. All efforts toward unionization ultimately yielded to combinations of employer intimidation, police force, and deep-rooted community hostility toward unions and “outsiders.” Yet the most effective deterrent to unionization remained the vast pool of cheap white labor, desperate for work, and the army of black labor at the extreme margins of subsistence.14

Black southerners were the first to absorb the economic downturn of the 1920s. The ravages of the boll weevil and the post-World War I economic slump stimulated a mass exodus of people “fleeing from hunger and exposure” in the countryside. African Americans dominated the rural movement to southern cities during 1922-24. In the latter part of the decade, whites began to follow in growing numbers. Rural refugees crowded into growing slums, where work was often irregular or nonexistent. As the economic squeeze tightened, white workers steadily took away what had been traditionally black jobs. Some towns passed municipal ordinances restricting black employment. But in most cases, intimidation and appeals to racial loyalty were most effective in securing jobs for whites.

In several cities, white terrorist organizations mobilized the frustration and helplessness of unemployed whites into sporadic drives to claim jobs held by blacks. In 1930, the Black Shirts marched up Peachtree Street in Atlanta with banners demanding, “Niggers, back to the cotton fields—city jobs are for white folks.” They forced Atlanta hotels to replace black bellhops with whites and pressured for the employment of white domestics, street cleaners, and garbage collectors. Future Governor Eugene Talmadge and the Georgia commissioner of agriculture were among the prominent members of the association. Although such extremist organizations were short-lived, black displacement by whites was widespread. In 1932, a New Orleans city ordinance that would have reserved jobs on publicly owned docks for “elig...