![]()

1 The Rule of Priests

At the end of his prophetic book, Ezekiel receives a final vision of temple and land. Whether this was intended as a utopian vision or a blueprint for the restored community is much debated.50 The vision opens with a detailed description of a temple. An angelic figure leads Ezekiel into the heart of the temple and back out again, completing the tour just in time for the prophet to witness the return of YHWH’S glory to the sanctuary (40:1–43:12). The angel then relays to the prophet the “Law of the Temple” (תרות הבית). The law opens like other Israelite law codes with instructions about the altar: its construction and consecration (43:13–27). This is followed by rulings concerning the conduct of the prince (44:1–3), the priests (44:6 – 31), the allocation of land for the priests and prince (45:1–8), the prince (45:9–17), and the festival calendar and offerings (45:18–46:24).

Outlining the contents of the Law of the Temple highlights the way in which the regulations about the priests and the allocation of land have intruded into the instructions about the prince (44:1–3; 45:9–17).51 The intrusive material is introduced by vv. 4–5:

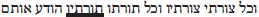

Then he brought me via the north gateway to the front of the temple. I looked and behold the glory of YHWH filled YHWH’S Temple, and I fell upon my face. YHWH said to me, “Human, mark well, look carefully, and listen attentively to all that I will tell you concerning all the ordinances of YHWH’S Temple and its laws. Mark well the entrances of the temple and all the exits of the sanctuary.”

Most of the elements in vv. 4–5 are adaptations of material found elsewhere in Ezekiel’s vision, especially 43:1–11.52 The composer of these verses has clearly sought in his selection to highlight the significance of what follows, but the result is somewhat jarring. The description opens by returning Ezekiel to precisely the location where he stood when YHWH’S glory appeared (43:5).53 Since the east gate was shut permanently following the arrival of the glory, the prophet must make a detour and enter via the north gate.54 The prophet has returned to the same location so that he can see YHWH’S glory filling the temple for a second time. Since the return of YHWH’S glory to the temple should be a single, climactic event, its repetition is narratively incongruous. The description of the return of the divine glory uses wording that is almost identical to that found in 43:5,55 and Ezekiel’s response is again to fall on his face (cf. 43:3). As at the first appearance, the angel addresses the prophet, but on this occasion, the angel’s very first words from 40:4 are blended with the references to the Law of the Temple from 43:11–12.56

Human, look carefully and listen attentively and mark well all that I will show you (40:4).

Make known to them the form of the temple, its structure, its exits and its entrances, and its entire form, and all its ordinances and its entire form and all its laws (43:11).

Human, mark well, look carefully, and listen attentively to all that I will tell you concerning all the ordinances of YHWH’S Temple and its laws. Mark well the entrances of the temple and all the exits of the sanctuary (44:5).

By appropriating the opening speech of the angel, the composer of these verses has realigned the beginning of the Law of the Temple and relegated 43:13 –44:3 to a subordinate status. The two major sub-divisions of Ezekiel’s vision – the Vision of the Temple and the Law of the Temple – are distinguished by attributing them to different senses. In the opening of the temple vision the prophet was permitted to see (מראה) the new temple (40:4), but for the Law of the Temple he will be told (מדבר) about the ordinances (44:5). In 43:11 Ezekiel is tasked with revealing various details about the temple, “all its laws”. In contrast, 44:5 draws attention to one of these: the entrances and exits of the sanctuary.57 These will be the focus of 44:6–16, or more precisely these verses are concerned with who it is that may enter the sanctuary through those entrances and exits.

The title of the second section of Ezekiel’s vision, “the Law of the Temple”, together with the references to ordinances and laws in vv. 4–5, incline the reader to anticipate a series of regulations. In fact, what the reader encounters is a divine oracle, which consists of a reproach in vv. 6 – 8 and YHWH’S word of judgement in vv. 9–16. The divine word of judgement is not simply a description of punishment, but unusually includes within it various stipulations about sanctuary access. The two parts of the divine oracle are introduced by the familiar prophetic introduction to divine speech, כה אמר אדני יהוה, “thus says Lord YHWH” (vv. 6, 9). Only from v. 17 onwards do we find an unadulterated list of stipulations that vv. 4– 5 caused us to expect.

The expectations of the reader are further unsettled by an apparent disjunction between the two parts of the divine oracle. There are three difficulties. First, Israel is sharply reprimanded in the second person plural, but the word of judgement that follows is not directed against Israel. Instead, Israel is spoken of in the third person and it is the Levites who are judged 58 Secondly, Israel’s failure is described in quite different terms in vv. 6 – 8 as compared to vv. 10–16. Verse 7 accuses Israel of admitting foreigners to the sanctuary who profaned it, an action that is vehemently condemned in v. 9. But the rest of the word of judgement describes a different sin: Israel’s preference for idol worship (vv. 10,12,15). Are these to be envisaged as related or distinct infractions? Thirdly, we would expect the reproach to refer to past transgressions and the word of judgement to draw future consequences. In fact, the word of judgement moves repeatedly between past and future. The verses oscillate between past actions, typically expressed with qatal and wayyiqtol forms (vv. 10a, 12a, bα, 13bß),59 and the consequences that are to result, expressed with weqatal and yiqtol forms (vv. 10b–11,12bß–13bα, 14).60

Such an obvious textual wrinkle might ordinarily suggest recourse to a literary-critical solution. Surprisingly, perhaps, such solutions have rarely been ventured and the unity of Ezek 44:6–16 has almost universally been assumed.61 Thus, in his extensive study of the temple vision, Konkel notes the near unanimity of scholarship on the issue and insists that only the appearance in v. 7bß of a covenant – an idea otherwise unattested in Ezekiel’s temple vision – is problematic. “Eine weitere Infragestellung der Einheit des Abschnitts empfiehlt sich auf dem Hintergrund der synchronen Analyse nicht. Der redundante, mit Parenthesen durchsetzte, echauffierte Stil des Abschnitts ahmt die mündliche Rede nach. Der Text folgt dabei aber durchaus einer klaren Logik.”62 The difficulties we have exposed raises questions about the supposed “clear logic”, and Konkel’s appeal to orality evades the issue rather than solving it.

Amongst recent interpreters, only Rudnig has felt the force of the difficulties we have described. According to Rudnig the original oracle in 44:6 – 7a, bß was directed against the pretensions of the first exiles (the Jehoiachin-golah) who were accused of allowing foreigners within the temenos. It was later reworked in vv. 7bαγ, 8b as a protest against certain cult personnel. The programmatic distinction between priests and Levites is a later stage of development.63 Rudnig notes the repetitious nature of vv. 9–16 and identifies vv. 9–10, 13–15 as the original continuation of the reproach in vv. 6–8. The expansions in vv. 11–12,16 further clarify the roles of the Levites and sons of Zadok by reworking some of the existing expressions.64 Thus, Rudnig resolves many of the difficulties we have observed, but only be reducing the oracle to fragments.

If we are to make progress in understanding the oracle, it will be necessary to examine the separate parts of the oracle. Neither Konkel’s synchronic perspective nor Rudnig’s redactional analysis is sufficient for the task, though both are valuable in their different ways. The crucial ingredient in this study will be attention to possible inner-biblical interpretation. Since we have observed a discontinuity between the reproach and the judgement, we will examine the two parts of the oracle in turn. In each case we will begin with the main protagonists: the foreigners in vv. 6–8, and the Levites in vv.9–16. Beginning with the identity and characterization of these two groups, I will argue that it is the inner-biblical allusions that have given the oracle its distinctive shape.

1.1 yhwh’s Reproach of Israel

However complex the present form of the divine oracle is, the initial cause for YHWH’S ire is the presence of foreigners in the temple. Perhaps unsurprisingly critical efforts have focussed on identifying the situation that provoked the oracle. Who were the unspecified foreigners that had been permitted into the temple? Can we relate the oracle to foreigners known elsewhere in the Old Testament or in other contemporary historical accounts? The primary source of information about the identity of the foreigners is the reproach in vv. 6–8, but it does not provide a simple characterization of them.

1.1.1 The Identity of the Foreigners in Ezekiel 44

YHWH’S reproach of Israel comprises at least three distinguishable accusations, each of which concerns the way that foreigners have been given access to the cultic worship of YHWH.

Enough of all your abominations, House of Israel,

in your admitting (בהביאכם) foreigners – uncircumcised in heart and flesh – to be in my sanctuary (במקדשי), to profane it, my house (את ב־יתי),

in your offering (בהקריבכם) my food,65 fat and blood, and they 66 have broken my covenant in addition to all your abominations.

And you did not keep (שמרתם) the charge of my holy things, but you set them 67 as keepers of my charge in my sanctuary.68

For each of these charges in vv. 7–8 the verbal action is key to the accusation: הביא, “to admit”, הקריב, “to offer”, שמר, “to keep”. Each is a cultic action that has been abused. The first two accusations begin with temporal clauses that are introduced with ב and the infinitive construct. They are juxtaposed with one another without a conjunction suggesting that they are contemporaneous, but distinguishable actions.69 The first accusation is somewhat complicated by the final clause, לחללו את ב־יתי, “to profane it, my house”. Apparently, this clarifies the admission of trespassers into the “sanctuary”, but elsewhere in Ezekiel’s Vision of the Temple, מקדש, “sanctuary” and בית, “house” are not synonymous terms: מקדש refers to the temple building proper and בית to the whole sacred area (cf. 43:21). In addition, לחללו את ב־יתי is tautologous. Consequently, it has often been suggested that את ב־יתי is a gloss.70 The second accusation presupposes the first, but goes beyond it. The foreigners were not only admitted to the sanctuary, but were present at the sacrifices. To these two serious charges is brought an additional one, which appears to be an exacerbation of the accusations in v. 7. Not only did the Israelites admit foreigners and allow them to be present when food was offered, but they even charged them with protecting the sanctuary.

There has been no lack of proposals for identifying these foreigners who entered the sanctuary, offered sacrifices and took charge of its security. Israel’s history prior to the exile has been scoured for potential candidates. Within critical scholarship it was long claimed that the foreigners of Ezekiel 44 were the netinim, cultic servants mentioned in 1 Chronicles, Ezra and Nehemiah. These, it was argued, were descendants from the Gibeonites and other foreign captives who were forced to undertake menial tasks for the temple. Ezekiel 44 removes those tasks from the netinim and assigns them to the Levites. The main lines of this interpretation were already articulated by Wellhausen in his Prolegomena,71 and further developed in the twentieth century.72 Significant elements of this interpretation have, with justification, been abandoned in recent years. Key elements of this hypothesis depend upon evidence known only from the Mishnah, some of which is in tension with the biblical texts. In particular, there is no ancient evidence that connects the netinim and the Gibeonites,73 and proof that they were foreign is also lacking.74 In addition, there is no evidence in Ezekiel 44 that the Levites were given roles previously held by the foreigners. Duguid argues that the foreigners are the Carites who guarded Joash in the temple during the coup against Athaliah (2 Kings 11:4, 19). Since we know almost nothing about the Carites, Duguid’s proposal is pure speculation, and he too assumes the Levites took over roles previously held by foreign servants 75 Galambusch argues that th...