![]()

Part I

Religion at the United Nations

![]()

1 Engaging on global issues in a UN setting

Religious actors

Katherine Marshall

Many FBOs (Faith Based Organizations) often either refer to this organism [the United Nations] as though it were one homogenous entity or complain about the confusion engendered by so many bodies all being part of “the UN.” This is a very real concern because unless there is a deep knowledge of the system, which many in the UN themselves struggle to acquire, it can take a lifetime to understand whom exactly to reach out to, let alone partner with, and how best to do so.

Azza Karam, UNFPA

The United Nations (UN) system has evolved from rather Spartan beginnings in 1945 into a vast, sprawling set of organizations with numerous outposts in all world regions. The system includes the “core” UN headquarters and a host of specialized agencies, commissions, councils, etc. It includes peacekeepers, mediators, doctors, educators, financiers, statisticians, and media specialists. There is a sports office and a new agency for women. New offices are emerging to deal with the complex, interlinked issues that the threat of climate change presents. A complex set of human rights agencies are part of the system as are regional offices concentrating on specific aspects pertinent in that part of the world. A feature of the system is periodic international conferences or series of conferences on specific topics (the climate change summit in Paris, COP21, in December 2015, is an example); their mission is to focus world attention and spur action on issues of global concern.1

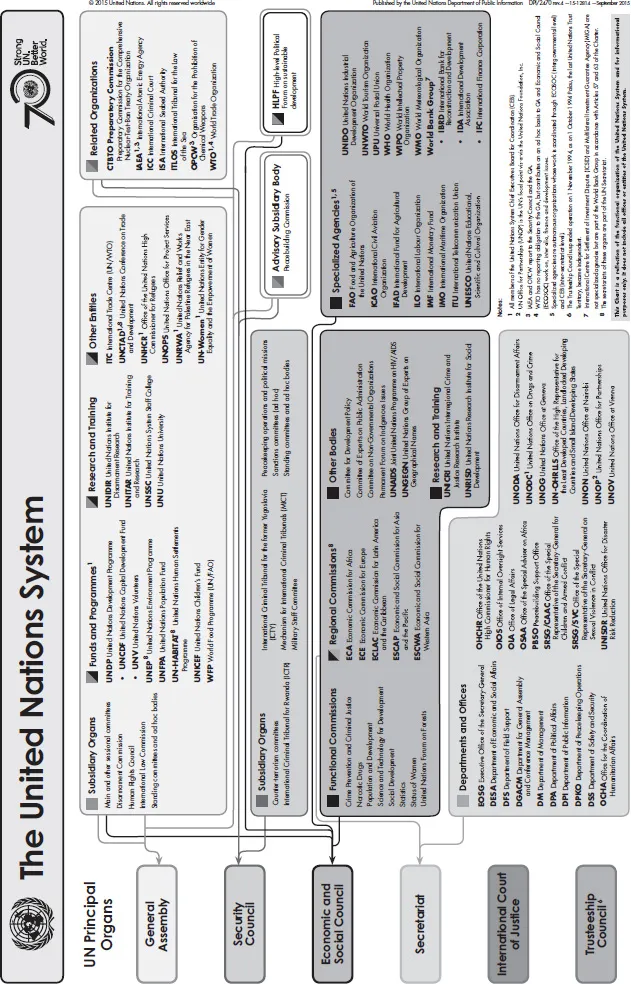

The following image,2 the product of a hostile group fearing “world government”, nonetheless conveys a sense of the geographic reach of the United Nations system and points to a key feature: its complexity.

This complexity is relevant to the issues that emerge in an exploration of religious engagement within the United Nations system, for the engagement differs markedly among different parts of the UN. A first question is how an organization whose membership is thoroughly grounded in the nation state political system in fact relates to the vastly complex religious institutions and practices that, for the most part, stand apart from that system. This weaves in the increasing involvement over the years of various civil society institutions in UN affairs but it also elicits questions about what secularism means in practice at the transnational level. Different nation states approach the topic so differently (Casanova 1994; Calhoun 2011) that a common approach has proved impossible. Notwithstanding common and over-simplified notions that secularism means simply the exclusion of religious matters from affairs of state, in reality many very different understandings and arrangements govern relations between states and religious institutions, on topics that range from religious engagement in education matters to administration of religious facilities to family law. These differences in approach are reflected in the various forms of religious involvement in United Nations governance and practice over time and by different parts of the UN system writ large.

Figure 1.1 Engaging on global issues in a UN setting

Second are questions turning around values and ethical standards. It is commonly stated, in a loaded fashion, that the religion of the United Nations is human rights. What is implied by such statements can be positive: that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and associated covenants provide a common framework of beliefs and commitments that situate debates and action within a set of universal values. The linking of human rights and religion can also carry a pejorative sense, suggesting an unreasoning zeal and determination to proselytize a specific set of beliefs that is insensitive to diverse cultures and norms. Where the interface with religious institutions and beliefs is involved this is understood by some to involve a specific (and, by implication, narrowly understood “Western”) approach to the rights of individuals that conflicts with values intrinsic to religious teachings (rights of LGBTQ individuals are an obvious example but child rights and age of marriage also have been questioned). The result is a questioning in some settings, by some religious actors, of some elements of human rights that are seen either as undermining important social values (often framed in relation to families) or threatening the integrity of a culture or community. What, then, we must ask, are the values issues at stake and how do the asymmetrical institutions involved address them, especially when they appear to be in conflict?

A religious United Nations?

A comprehensive analysis of the history of religious engagement and the United Nations has yet to emerge. The various analytic efforts that exist are best described as descriptions and commentary on what happens in different parts of the United Nations “elephant”. As with the proverbial elephant seen so differently by blind men, religious links look very different depending on one’s vantage point or even moment in time. So do the aspirations of what religious engagement should or might be. These range from a deep integration of religious institutions in the United Nations system (with, for example, what has been termed a “Spiritual Council” paralleling the Security Council) to solid formal representation offering both spiritual and practical counsel, to formal exclusion from deliberations because religious perspectives do not belong there.

Analyses of religious roles include reflections on the spiritual engagement of various leaders (especially Dag Hammarskjöld, 2006), accounts of the roles played by specific influential individuals and groups (for example the Quakers, Frank Buchman of Moral Re-Armament), and accounts of two global interfaith organizations established and developed with specific reference to the United Nations system (Religions for Peace and the United Religions Initiative). Considerable attention has focused on the unique example of the Holy See, which is represented as a nation with observer status. But the role of religious ideas and actors broadly has been the subject of remarkably little attention in the intellectual histories of the United Nations. This is in part because, especially in the early years, religious beliefs had a certain taken-for-granted character or, alternatively, they were de facto considered taboo. More recently it reflects both the sheer complexity of the topic and its diverse manifestations.3 In contrast, considerable analysis has been devoted to religious influences and roles (and ways in which they were absent) in the formulation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Glendon 2001).

Religious issues reappear on the agenda

During the formative years of the United Nations (and the predecessor League of Nations) the focus was squarely on nation states as the appropriate arena for international relations. Civil society representation and engagement had little recognition in the work of the United Nations (positive and negative) and that included religious actors. Activist (and self-described Quaker Buddhist) Scilla Elworthy commented on how little impact growing civil society activism had in the past:

The 1982 Second UN Conference on Disarmament in New York … attracted an extraordinary demonstration. I was working at the time to lobby on behalf of NGOs at the United Nations. On one Sunday, there were a million people protesting in New York. The demonstrators filled Central Park from end to end, and side to side. The cops started the day hostile, and at the end they had peace badges on their ties. It was one of the most successful demonstrations of its kind, ever, and the New York Times devoted five pages to the events. But the next day I went into the United Nations building and the continuing deliberations of the Conference, then in its third week. And there was no discernable effect whatsoever of the events outside.

(Elworthy 2010)

Equally significant in shaping religious approaches was the “secular paradigm” that predominated in the post war era, coloring both thinking and behavior. It was in part a response to the explicit atheism of the USSR and the People’s Republic of China, and it muted and even blinded many to religious institutions and issues. Even when religious issues and actors were obviously relevant, Cold War politics tended to keep them off the agenda. Discussions about human rights were skewed by the latent tensions around the very topic of religion (Ignatieff 1999).

The taboos lost much of their grip with the end of the Cold War and pivotal events such as the Iranian Revolution of 1979. And the blinkers that blinded many to the vigorous religious institutions that continued to thrive during the “silent phase” were slowly removed. From 1990 on, the rise of tensions within and with Muslim nations was unmistakable. And a new set of issues gained prominence as the United Nations Conference on Population and Development in Cairo (1994) and the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing (1995) conferences shone a spotlight on women’s rights, reproductive and sexual health, and the values issues associated with them. No longer could it be said that religion was invisible or irrelevant within United Nations circles.

Religious initiatives post 1990

Two significant developments are worth mention. The first is the emergence of a set of dialogues and efforts that have aimed to bring religious topics explicitly into the United Nations system. These include deliberate efforts aimed to engage religious actors on issues of war and peace that largely fall today under the heading Countering or Preventing Violent Extremism. The second is the emergence of a number of contested issues that are perceived as religious in nature, centering on women’s rights and particularly reproductive health. After Cairo (1994) and Beijing (1995) these issues have taken on a problematic cast that extends well beyond the immediate topics at stake. They are referred to with the abbreviation SRHR (sexual, reproductive and health rights) in United Nations policy documents.

Proposals to raise the profile of religious actors and to enhance formal engagement with religious institutions in the United Nations have ranged from efforts to devote days (or a decade) to religious tolerance and related topics – one result is Interfaith Harmony Week, now a regular annual feature – all the way to a determined group whose vision is full and formal representation of religious leaders as part of the United Nations. In 2015, the General Assembly approved an International Day of Yoga, amid considerable debate as to whether this involved religious beliefs. In introducing the resolution, the observation was that “for centuries, people from all walks of life have practiced yoga, recognizing its unique embodiment of unity between mind and body. Yoga brings thought and action together in harmony.”4

Religious tensions and violence associated with religious identities have, especially since September 11, 2001, led to a sharp increase in discussion and action on topics related to religion. Among specific actions was a high-level group of experts appointed by Secretary-General Kofi Annan, to explore the roots of polarization among societies and cultures today, and to recommend a practical program of action.5 The group’s report led in 2007 to the creation of the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations which has operated for a decade as part of the United Nations under a unique arrangement. Its mandate is to promote dialogue and tolerance, with a particular focus on media and youth. In May 2007, the General Assembly appointed a task force also focused on interreligious harmony (and thus tensions and intolerance).

The second significant religious influence at the UN is the appearance of a series of events that have had less positive echoes and contribute to a general unease among some United Nations member states and operational staff of UN agencies. An example is the Millennium Summit of Religious Leaders in August 2000, on the eve of the Millennium Summit of World Leaders at the United Nations to mark the turn of the millennium. That interreligious meeting was the most ambitious of its kind and opened in the General Assembly Hall with great fanfare. However, various controversies detracted from the positive glow. These included the dis-invitation of the Dalai Lama, largely in deference to China’s views, appalling organization of the event (including an after effect of financial mismanagement), and tensions linked to a large presence of militant Hindu groups, which disrupted a number of sessions. The event included long and contentious speeches and statements that seemed to engage the United Nations in creating a Spiritual Council that in fact had not received any blessing from United Nations leadership. Various UN officials have expressed a reluctance to have any involvement with religious groups in the wake of this event. (Marshall 2001).

Religious engagement at the UN: focal topics

The religious groups that are active in United Nations affairs are highly varied as are their activities and points of view. It would be difficult to identify any among the myriad topics in which some United Nations agency is involved w...