![]()

Chapter 1

The Institutions

In 1923, Donald G. Tewksbury published what has become a classic in the history of American higher education and the major source for those interested in the rationality and stability of antebellum American colleges. The Founding of American Colleges and Universities in the United States was completed at Teachers College, Columbia University, an institution devoted to the application of science to every level and aspect of education.1 Teachers College was committed to the modernization of education through the use of the tools of research and rational planning and it was a leader in the establishment of efficiency, centralization and a value-free scientific curricula as goals for America’s schools. Its professors, no matter what particular version of Progressivism they advocated, searched for a science-based metaculture that would provide the country with professional educators who could remove the educational system from the troublesome realms of local and cultural politics. To investigators with such views and goals, the decentralized, denominational, ethnically divided antebellum college system seemed to be the antithesis of sound educational policy.2

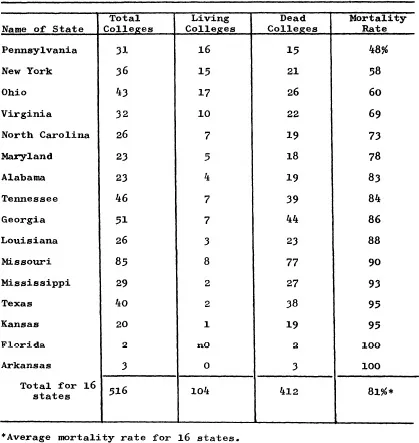

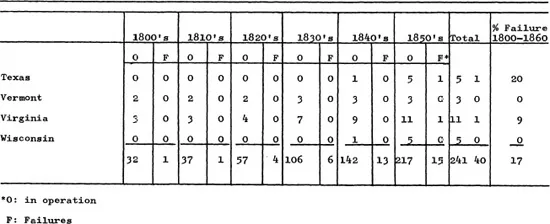

Although Tewksbury’s work was written in a highly objective tone, it reflected the Teachers College perspective. Rejecting previous estimates by Cubberley, West, and Dexter of the number of colleges that were founded, he went to session laws of various states to identify both foundings and failures. The result of his study was a story of educational chaos, chaos caused by an excess of democracy on the frontier and the irrationality of denominational competition. Instead of discovering some two hundred foundings before the Civil War, as estimated by Cubberley and Dexter, he found five hundred sixteen in just sixteen states, and hinted that similar founding rates occurred throughout the remainder of the country. He never specified the total number of foundings before the Civil War, but if his average for the sixteen (mostly Southern) states are projected to the remaining non-New England states, the result is over nine hundred colleges, or one for every one thousand white males age fifteen to twenty in the United States in 1850.3 Tewksbury concluded that 81 percent or over seven hundred of these colleges failed, and he explained the failures as the outcome of legislatures, without any thought to the needs for stability, allowing poorly funded, unattractive, and low-quality institutions to obtain charters. The results of political control of higher education were an overabundance of pretentious and unstable schools which prevented the rise of efficient, large-scale institutions. (Table 1.1)

Only in New England, Tewksbury stated, was such chaos and irrationality avoided. He did not mention the problems of elitism and religious prejudice in the region, and he did not point out that New England’s colleges had benefited from the type of state economic support withheld from the colleges in the new states.4

Table 1.1

Tewksbury’s Table of Mortality of Colleges Founded Before the Civil War in Sixteen States of the Union

Tewksbury’s work is still valuable, but it has several significant faults which call for the rejection of his estimates of foundings and failures and for a modification of his interpretation of the causes underlying the development of antebellum higher education. For at least three states, Ohio, Missouri, and Texas, official lists of college charterings do not match his findings.5 But more importantly, his choice of the issuance of college charters as the indicator of foundings is very questionable. The issuance of a charter did not mean that a college was established. And even if an institution was founded under the legislative grant, it may not have operated as a college or competed for college students. It may have confined itself to what are now called primary and secondary education.6

Tewksbury made several very strong assumptions to arrive at his interpretation of the causes of the supposed college explosion. He assumed that colleges were founded to compete with other demoninations rather than to serve intra-denominational needs, and he assumed that any degree of denominational affiliation reflected domination of a college by the religious body. He implied that any ideological differences among the colleges were insignificant, irrational, and premodern, and he overlooked the possibility that denominational lines coincided with very significant class, ethnic, and political differences.

Tewksbury’s use of survival into the twentieth century as the criteria for success of the colleges was ahistorical in concept, masked the timing of failures and left his readers with little indication as to when and why particular colleges failed. Furthermore, he deemphasized the number of foundings and failures before the late 1830s and the instability of state institutions.7

Only two pages of the Founding of American Colleges were concerned with the presentation of evidence on foundings and failures. The remainder of the book was devoted to details on the institutions that survived into the 1920s and with interpretative comments on the instability and irrationality of the early system. Tewksbury included only one short table listing the numbers of foundings and failures by state and this was for sixteen states only. Twelve of the states in the table were in the South, although much of his discussion of the reasons for failures seemed to be directed to the Midwest.8 (Table 1.1)

Tewksbury referred readers seeking more detail to a file he had placed in the Teachers College library. But this file cannot be located and it has not been cited in a published work since the appearance of his book. The loss of the file has left investigators with little specific information—the detail needed to verify Tewksbury’s estimates, to check his assumptions, and to use his original efforts in other investigations.9 Because Tewksbury’s work is questionable and because the estimates by investigators such as Cubberley were not accompanied by detailed analyses, a new search for both foundings and failures was conducted for this study. Instead of using charters as an unambiguous indicator of foundings, contemporary and historical sources likely to mention operating colleges were searched to identify colleges active in the period between 1800 and the outbreak of the Civil War. Post Office directories, atlases, national, state and local almanacs and registers, denominational publications, collections of college catalogs, and histories of the states and education within them were surveyed for any mention of a college in operation. Once a mention was noted, attempts were made to verify that the male or coeducational institution actually taught students in an educational track leading to a college degree and that contemporaries regarded the institution as a college.10

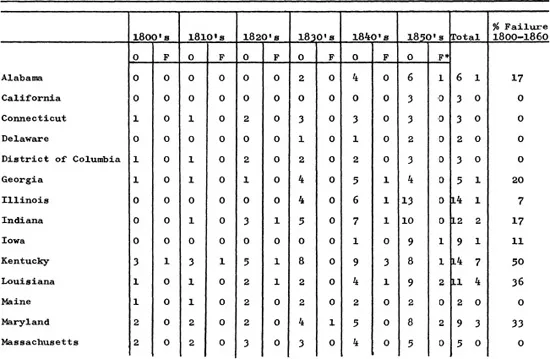

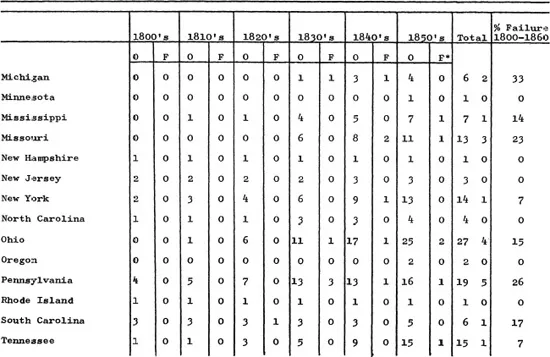

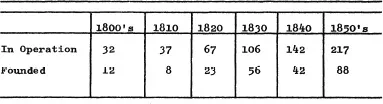

The result of the search, which included the hundreds of sources examined in a tracing of the lives of twenty-four thousand college and professional school students of the period, gives a different picture of the stability of antebellum higher education from that put forward in The Founding of American Colleges and Universities. Two hundred and forty-one institutions, including some seventy suspected of academy or preparatory operation only, were identified as operating during the period. (Tables 1.2, 1.3)

Seventy percent of the total survived into the twentieth century and 80 percent survived until the Civil War. If Catholic colleges are removed from consideration, the failure rate before the Civil War was 14 percent and if nondenominational colleges are also deleted, the sixty-year failure percentage was 10 percent. If state institutions are also excluded, the estimate drops to less than 8 percent.

The timing of the founding of colleges did not follow the pattern Tewksbury implied. Although he never attempted to construct a decade-by-decade series for all college foundings, he pointed to the 1830s, the Jacksonian years, as the beginnings of the irrational growth of the number of colleges in the country. But the increase in the number of schools began much earlier than he thought and the expansion was not in isolation from other changes in the American educational system.

Approximately twenty colleges were in operation in the United States in 1800. By the 1850s, two hundred seventeen were open. This tenfold increase began in the first decade of the century when twelve additional institutions either first began or resumed operation—a 60 percent increase over the first year of the century. Perhaps due to the turmoil of the years of conflict with England, the 1810s added only eight colleges. The 1820s began the accelerated growth of institutions with a 50 percent increase in the number of colleges in operation. The 1830s had a near doubling of the number of institutions in operation, but the economic pressures of the 1840s resulted in a slowdown of the growth rate. The 1850s experienced a 50 percent expansion with eighty-eight new colleges being founded. (Tables 1.2, 1.3)

Table 1.2

Distribution of Liberal Arts Colleges In Operation by State and Number of Failures By Decade.

Table 1.3

Liberal Arts Colleges In Operation and Founded, 1800-1860

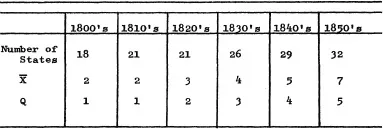

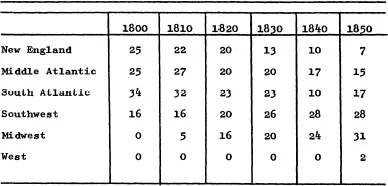

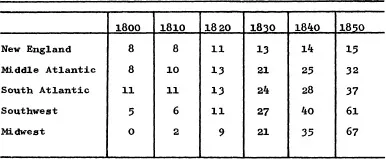

The growth in the number of colleges coincided with a shift in their geographic distribution. The colleges followed the movement of the American population to the West. New England’s share of the colleges dropped from 25 percent to 7 percent in the sixty years, while the combined share of the Southwest and Midwest increased from 16 to 60 percent. The new areas of the country acquired colleges early in their development, and even the three states without colleges by the 1850s, Arkansas, Florida, and Kansas, had made attempts to found some. Arkansas chartered over thirty colleges and universities, Florida attempted to found a state system, and Kansas chartered eighteen universities and ten colleges in just the five years between 1855 and 1860.11 (Tables 1.4, 1.5, 1.6, 1.7)

Table 1.4

Number of States With Liberal Arts Colleges And Average and Standard Deviation of Number of Colleges by State

Table 1.5

Colleges in Operation by Region and Decade as a Percent of All Colleges in Operation

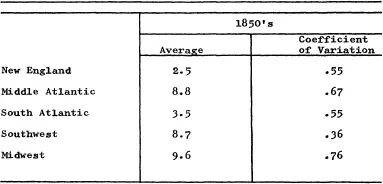

But the growth of colleges was not a simple matter of the addition of new states. Over the six decades a much more complex process was at work leading to increasingly diverse educational profiles among the various states and regions. Colleges spread from eighteen to thirty-two states in the six decades, with the average number of colleges per state increasing from two to seven. At the same time, the states and regions became differentiated in respect to the number of colleges they maintained, reflecting state policies, denominational differences, and the degree of elitism in the states.

The relative shift of college location and the differentiation of the states and regions came in uneven steps. New England’s share of the institutions showed only a slight decline until the 1830s because of the relatively slow growth of colleges across the country and because three new colleges were opened in New England in the 1820s. After the 1820s, New England would add only four colleges, despite its population growth and its ethnic diversification; and one of the four had to wait until after the Civil War to receive an official charter because of the bias in New England against Catholicism.12 By the 1850s, the small number of college foundings in New England led to its average number of colleges per state being less than one-half the national average; the frontier state of Oregon had more operating “colleges” than three of the New England states.

Table 1.6

Colleges in Operation by Region and Decade

Table 1.7

Average Number of Colleges in Operation Per State in the Regions and Coefficient of Variation

The older Southern states and the Middle Atlantic region did not face such drastic declines in the percentage of colleges in operation. The South Atlantic share dropped from the country’s largest in 1800 to the third largest in the 1850s, although the number of colleges in the region increased threefold. The experience of the South Atlantic states illustrates that the expansion of the 1830s was not confined to the West. In that decade the number of colleges in the old South nearly doubled, and only the District of Columbia maintained the same number of colleges that it had in the 1820s. In the Middle Atlantic states there was a greater increase in the number of colleges in the sixty years. Although their share dropped by 40 percent, two of the region’s three states, New York and Pennsylvania, each had as many or more colleges than any other state except Ohio, Tennessee, and Illinois in the 1850s. Pennsylvania had more colleges than any state except Ohio.

The changes in the relative standing of the regions was accompanied by an increase in diversity among them, reflecting differences in chartering policies, denominational interest, and the ability to muster economic support for education. The Midwestern states had the highest variance, primarily due to policy decisions by the state governments. Ohio, for example, had twenty-five operating colleges in the 1850s while Michigan had four. One of the reasons for this difference was that Michigan pursued a very restrictive chartering policy until the Republicans took power in the 1850s. Ohio had always maintained a liberal policy, although it offered almost no economic support to its colleges.13 But across the country, political preference in nationa...