1. The Business of Slavery and the Making of Race

In 1783 the Rhode Island General Assembly voted to free Amy Allen, who sued for freedom on the basis that she was not black; Allen successfully claimed to be “an abandoned white child raised by an enslaved mother.”1 Her whiteness exempted her from any suspicion of slavery. On the other hand, because blackness was akin to slavery, free blacks had to safeguard their status. In 1785, Jane Coggeshall, who had been emancipated in 1777, petitioned the General Assembly to confirm her freedom, as she feared her former master’s family sought to re-enslave her.

Whereas, Jane Coggeshall, of Providence, a negro woman preferred a petition and represented unto this Assembly, that she was a slave to Captain Daniel Coggeshall, of Newport; that in March, A.D. 1777, the enemy being then in possession of Rhode Island, she, together with others, at every risk, effected their escape to Point Judith; that they were carried before the General Assembly, then sitting in South Kingstown, who did thereupon give them their liberty, together with a pass to go to any part of the country to procure a livelihood; that she hath lived at Woodstock and at Providence ever since; that during the whole time she hath maintained herself decently and with reputation, and can appeal to the families wherein she hath lived with respect to her industry, sobriety of manners, and fidelity; that of late she hath been greatly alarmed with a claim of some of the heirs of said Daniel Coggeshall upon her still as a slave; that as she has enjoyed the inestimable blessing of liberty for near eight years, she feels the most dreadful apprehension at the idea of again falling into a state of slavery.2

The Assembly voted to declare Jane Coggeshall “entirely emancipated and made free.” This black woman, however, was worthy of freedom only because of her “industry, sobriety of manners, and fidelity.” In the wake of the Revolutionary War, the members of the Rhode Island Assembly and white northern society in general accepted that whiteness in and of itself was enough to warrant freedom but felt that blackness necessitated certain characteristics to earn freedom. For whites, freedom was an inalienable right; for blacks, it was a privilege. These racial assumptions, however, were a result of decades of legal race-making.

Unlike legislators in Massachusetts and New York, Rhode Islanders did not specifically identify who was eligible for enslavement, nor did they establish the condition as hereditary. They did not see a need to. Rhode Islanders’ immersions in the Atlantic economy allowed them to take black slavery for granted. However, it took nearly fifty years for Rhode Islanders to write race-based slavery into law. In 1652, colonial officials in Providence and Warwick banned the enslavement of “blacke and white mankind.”3 Twenty-four years later, in 1676, they prohibited the enslavement of Native Americans.4 Nevertheless, in 1703, the Rhode Island General Assembly legally recognized both black and Native American slavery, and by 1750 Rhode Islanders held the highest percentage of slaves in New England.5 This about-face reflected Rhode Islanders’ increased participation in the Atlantic economy.6

In Rhode Island, it was the business of slavery that brought the disparate towns and villages of this small colony together and encouraged the emergence of slavery. Before they committed themselves to the pursuit of commerce in multiple directions across the Atlantic Ocean, Rhode Islanders sought to restrict and even ban slaveholding; however, once they began to participate in the West Indian and Atlantic slave trades, they wrote slavery into law. By the 1730s, merchants, slave traders, farmers, distillers, and manufacturers had created a niche for themselves in the Atlantic economy, and a series of racist laws served the needs of a local economy already deeply entrenched in the West Indian and Atlantic slave trades.7 Moreover, the more dominant Rhode Islanders became in the slave trade, the more they relied on slave labor.

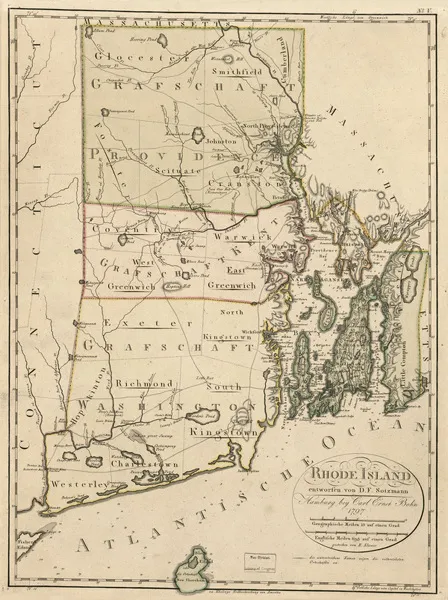

By 1750, 10 percent of Rhode Island’s population was enslaved—double the northern average. Enslaved people were heavily concentrated in the port cities of Newport, Providence, and the Narragansett Country, also known as South County, which was made up of the rural towns of North Kingstown, South Kingstown, Charlestown, Exeter, Wickford, Wakefield, and Peace Dale. Slave law in the colony also buttressed the business of slavery by explicitly protecting the property rights of slaveholders. Furthermore, these laws elevated all whites to the enslaver class, as it required them to supervise all slaves; at the same time, those laws relegated people of color to the status of dependents or potential dependents. The business of slavery in Rhode Island shaped not only the economy but also social standing and race relations.

Rhode Island had English sponsorship rather than a charter, and no single dominant religion. In other words, unlike other northern colonies, Rhode Island was not founded to promote a particular religious vision, nor was it established for economic gain. All four founders had been expelled from Massachusetts as a result of their “radical” religious beliefs.8 When Providence, Portsmouth, Newport, and Warwick, the colony’s four original towns, were finally united under a charter from the crown in 1644, they shared no central government and lacked even a collective vision. During the last half of the seventeenth century, conditions verged on anarchy as the towns battled over land and land boundaries.9 As Rhode Island scholar Sydney James writes, “Half the colonial period had gone by before Rhode Island was indelibly on the map—that is, before it enjoyed a flourishing local patriotism and achieved internal order, reasonable immunity from the territorial ambitions of its neighbors, and safety from British plans to merge it with a larger colony.”10

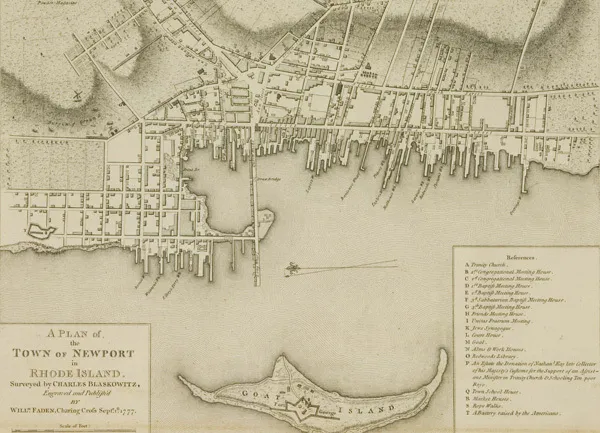

Amid this instability, there was one certainty: the ocean. Water-based commerce in and around the city of Newport quickly became the basis of Rhode Island’s trade economy; it was a likely enterprise for Rhode Island colonists, since water was what united them all (see maps 1 and 2). Rhode Island measures a mere forty by thirty miles, but five hundred of its square miles touch water.11 By the mid-eighteenth century, Rhode Island had become a permanent and prosperous colony, thanks to local investments in the business of slavery. Colonists supplied sugar plantations in the West Indies with slaves, livestock, dairy products, fish, candles, and lumber. In return, they received molasses, which they distilled into rum. This trade began in the late seventeenth century but flourished after 1730, when rum became a major currency in the slave trade.12 The West Indian trade propelled Newport out of Boston’s shadow and into the status of a major city and helped establish Providence as a major port.13

Between 1650 and 1860, an estimated ten to fifteen million Africans were transported to the Americas; nearly every major European power participated in the Atlantic slave trade.14 And while English colonists in North America were late and minor participants in the slave trade as a whole, Rhode Island slave traders dominated the American trade in African slaves. Newport would become the most important slave-trading port of departure in North America.

The West Indian and Atlantic Slave Trades

In Rhode Island, trade and political power went hand in hand. During the colonial period, most governors were from the merchant class; in fact, many of them were slave traders. The primary duty of the governor, who was elected annually through popular vote, was to negotiate between the General Assembly (the governing body that lived in Rhode Island) and an English authority, either the Board of Trade or the colonial agent in London.15 In other words, Rhode Island governors brokered trade agreements between the colonies and the mother country; consequently, promoting and protecting Atlantic commerce was in their political interest and was also a personal investment. Peleg Sanford, who acted as governor from 1680 to 1683, exported horses, beef, pork, butter, and dried peas to Barbados in exchange for sugar and molasses. Samuel Cranston won the annual vote for nearly three decades, serving as governor from 1696 to 1725; not coincidentally, he was a slave trader and ship captain.16 It was under the leadership of Samuel Cranston that Rhode Islanders fully committed to Atlantic commerce. Cranston cracked down on piracy, the major crown complaint against tradesmen.17 Rhode Islanders relinquished some of their autonomy in exchange for greater access to “legitimate” Atlantic commerce.18

Map 1. Rhode Island. Source: Carl Ernst Bohn, Heinrich Kliewer, and D. F. Sotzmann, Map of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (1797), Library of Congress, Map Collections, accessed August 3, 2015, www.loc.gov/item/2011589271/.

Atlantic commerce, the slave trade in particular, brought Rhode Island merchants, tradesmen, and farmers together. Cranston credited the emergence of commerce to the colony’s small size and proximity to the Atlantic, saying that “the reason of [commerce’s] increase (as I apprehend) is chiefly to be attributed to the inclination the youth on Rhode Island have to the sea. The land on said island, being all taken up and improved in small farms, so that the farmers, as their families increase, are compelled to put or place their children to trades or calling; but their inclinations being mostly to navigation.”19 More and more farmers and merchants recognized Atlantic commerce as their best opportunity for economic security.

Rhode Islanders’ eighteenth-century political autonomy and economic success coincided with their entry into Atlantic commerce. Great merchants, including various members of the Malbone, Banister, Gardner, Wanton, Brenton, Collins, Vernon, Channing, Lopez, and Rivera families, collected goods from all who would sell and redirected them to whoever would buy in Africa, the West Indies, and North American port cities. 20 Rhode Islanders exported lumber, beef, pork, butter, cheese, onions, cider, candles, and horses; they imported sugar, molasses, cotton, ginger, indigo, linen, woolen clothes, and Spanish iron. Merchants sent ships primarily from Newport to Antigua, Jamaica, Barbados, Guadalupe, St. Thomas, Marincio, St. Lucia, St. Christopher, Surinam, and the Bay of Honduras. These merchants also transported goods of their neighbors.21 Rhode Island merchants, like their counterparts throughout the Americas, held a particularly important position in colonial New England because their trade sparked secondary and subsidiary industries that employed most colonists.22

Prior to 1696, the English Royal African Company had a monopoly on all English participation in the Atlantic slave trade; Rhode Islanders began sending slave ships as soon as the monopoly was lifted. These voyages grew increasingly common and profitable; in fewer than thirty years they dominated the North American trade in slaves, and the slave trade evolved into one of the pillars of the local economy.23 The vast majority of the slave ships that embarked from British North America left from ports in Rhode Island, even though it was the smallest and least populated colony (see table 1). In the first quarter of the eighteenth century, Rhode Island slave traders sent 8 slave ships to West Africa and transported 948 Africans back to the Americas. All other New Englanders combined sent just 4 ships transporting 363 Africans. New Yorkers also sent 4 ships transporting 355 Africans, and southern colonists sent just 2 ships transporting 192 Africans to the Americas. Between 1726 and 1750, 123 slave ships embarked from Rhode Island and carried 16,195 African slaves to the Americas; in comparison, only 36 slave ships left from all the other New England colonies, carrying just 4,575 slaves. New Yorkers and Carolinians sent just 3 slave ships carrying 407 and 415 African slaves, respectively, while Virginians sent 2 ships transporting 247 enslaved people. Rhode Islanders’ participation in the trade increased even more dramatically over the next twenty-five years. Between 1751 and 1775, Rhode Island slave traders sent 383 slave ships transporting more than 40,000 enslaved Africans to the Americas; all the other colonies combined sent 132 slave ships transporting just less than 18,000 African slaves (figure 2). During the colonial period in total, Rhode Islanders sent 514 slave ships to the coast of West Africa, while the rest of the colonists sent just 189. As historian Jay Coughtry has argued, the North American trade in slaves was essentially the Rhode Island slave trade. Rhode Island slave traders made their money by playing it safe; they sailed small ships that allowed them to avoid long waits for slaves and the subsequent risk of disease on the African coast. In the first half of the eighteenth century, they sold 66 percent of their slaves in the West Indies, 31 percent in North America, and 3 percent in South America.24

However, the slave-trading business was not without serious risk and danger. George Scott, a Newport slave trader, nearly lost his life and livelihood when the “human cargo” attempted to take over his ship. During a voyage in 1730, as he transported ninety-six slaves from the coast of Guinea to the West Indies, the male slaves freed themselves from their chains. They killed three white watchmen, a doctor, a barrel repairer, and a sailor—by throwing them overboard. Scott’s crew then began shooting the slaves and barely suppressed the rebellion.25 Just two years later, slaves...