![]()

PART I

Violating Rights

![]()

1

A Regional Survey

It was August 4, 1976, at four o’clock in the afternoon, when [Doctor] Carlos Godoy Lagarrigue, aged 39, left the San Bernardo Hospital by car. He had just finished his daily ward round and was as usual on his way to his outpatient clinic in La Granja. . . . He never arrived. Somewhere along the way, he vanished and has not been seen or heard of since. His wife and children waited at home that evening, and continued to wait for years and years.

—A friend recalling the disappearance of

a young doctor in Chile; testimony to the Chilean National

Commission on Truth and Reconciliation

Understanding why people are tortured or disappeared requires, at a minimum, stepping back and getting up close—stepping back to identify key facts and trends, getting up close to hear personal experiences of abuse. In this sense, description is a first step to prevention. Any attempt to explain and prevent human rights violations must be based on an accurate understanding of past and ongoing abuses. Which rights have been violated in the region? How have these abuses changed over time? Are there significant cross-national differences? How does Latin America compare to other world regions? This chapter examines these questions, by presenting both quantitative trends and qualitative “snapshots” of particular episodes of abuse. It also provides eyewitness accounts of the human toll these violations have taken, showing a side of the story that numbers and figures can never entirely capture.

Types of Violation

Most people tend to think of violations when they think of human rights: torture, summary executions, genocide, arbitrary incarceration. There is indeed something captivating about human rights abuse, perhaps evoking deep-seated fears of pain and powerlessness. In general, human rights violations consist of noncompliance with internationally recognized human rights norms. While there are as many types of violations as there are human rights, this book focuses mostly on a particular set of civil-political rights known as physical (or personal) integrity rights. These rights involve bodily harm, usually but not exclusively at the hands of state officials, and consist of four key rights: freedom from torture, extrajudicial executions, disappearances, and political imprisonment. These violations also go by more common terms like repression and coercion.

This book emphasizes these violations because these are the abuses that have most elicited attention and shaped policy debates vis-à-vis Latin America. Not surprisingly, most of the research and testimonies on human rights focus precisely on these abuses. While violations of economic and social rights can be equally important, both ethically and pragmatically, we focus in this chapter and the next on those egregious violations that have come under the heaviest scrutiny.

That said, there is increasing consensus that all human rights are interdependent. Even if a hierarchy of human rights exists, the view is that Cold War debates over the primacy of civil-political versus economic-social rights are nonproductive and largely moot. All types of human rights are interdependent and necessary for human dignity, regardless of ongoing controversies over specific rights (e.g., debates over the importance of the right to a paid holiday). In view of this interdependence, issues like poverty and other economic-social inequalities are discussed in this book whenever possible alongside physical integrity rights.

International human rights treaties have defined physical integrity rights. For example, the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984) defines torture as

any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions. (Article 1)

In practice, some of the most common forms of physical torture include electric shock, bodily suspension, beatings, food and water deprivation, forced ingestion of chemicals, and sexual violence. Psychological torture includes threats of violence (often directed at loved ones), solitary confinement, forced observance of torture or killing (including of children and spouses), sham executions, and intense sleep deprivation. All these abuses have been prevalent in Latin America.

According to the Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons (1996), a disappearance is

the act of depriving a person or persons of his or their freedom, in whatever way, perpetrated by agents of the state or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of the state, followed by an absence of information or a refusal to acknowledge that deprivation of freedom or to give information on the whereabouts of that person, thereby impeding his or her recourse to the applicable legal remedies and procedural guarantees. (Article 2)

Various human rights treaties also define extrajudicial executions and political imprisonment. In general, extrajudicial executions refer to killings committed by governments outside of legal boundaries. Murders by paramilitary groups directly supported or instigated by governments fall into this category as well. The identity of the victim does not matter as long as the death is the result of excessive or illegal use of force by state agents. Political imprisonment is in turn the incarceration of people because of their identity, including their religion, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, or political beliefs.

There are different approaches to measuring these rights violations. On the one hand, we can count the number of human rights abuses (or “events”). Some truth commissions, for example, have followed this “events-based” approach in an attempt to reveal the overall magnitude of a situation. While this approach is ideal in many ways, bringing us closest to the truth, the practice of quantifying abuses is often fraught with guesswork or necessarily limited to a select number of years or cases—particularly in places where people who have been “disappeared” have never been found, or where the location of unmarked graves remains undisclosed.

On the other hand, for those who study systematically the causes of human rights abuse, it is important to collect measures for as many years and countries as possible. Since an events-based approach is not always feasible, scholars have opted for measurements that assess the overall level of abuse. Like other attempts at quantification, this “standards-based” approach can be imperfect. For example, one of the leading measures of personal integrity violations employs a three-point scale, reflecting the extent to which violations are frequent (more than 50 incidents reported in a given year), occasional (fewer than 50), or rare. While this kind of measurement is somewhat arbitrary and unable to differentiate between 100 cases of torture and 10,000, experts tend to view these measurements as relatively reliable. At the very least, they permit a general comparison of violations across countries and over time.

Historical Context: Colonial Legacies and State Formation

If human rights violations are closely related to states as political actors, these violations can only be understood by examining the historical context in which states form. In Europe, for example, states were forged out of a great deal of violence and coercion. In the developing world, the context in which states were formed is inextricable from the process of colonialism. This is certainly true in Latin America, where today’s human rights violations can be traced historically to the experience of colonial rule, which left an enduring mark on the region’s states. Attention to this historical context does not exonerate individuals today for their role in committing human rights violations; it merely helps to explain one aspect of a deeply complex phenomenon.

Contrary to popular images, colonialism itself was not particularly violent in Latin America. After the horror of the conquest, which took over 65 million lives (approximately ten times the number of victims in the Holocaust), European colonizers set out to control primarily through “consent” rather than brute force. This required empowering local allies, promoting sentiments of inferiority, and transplanting cultural traditions like religion and patriarchy. In short, colonialism thrived on ideological domination, an essential component of any repressive system.

When struggles for independence spread throughout the region in the early nineteenth century, states adopted the language of liberation and resistance (emblazoned in their constitutions and sometimes linked to the abolition of slavery), but they remained chained to the legacy of colonialism. As one observer notes, “unfinished revolutions” marked the era of state formation.1 Colonial domination shaped subsequent repression by leaving at least two important legacies: ideological systems of subjugation and economic disarray.

If new states governed themselves without the shackles of colonialism, they nonetheless inherited the idea that men were superior to women and that race was tied to privilege; thus, indigenous people and those of African descent, especially women, were automatically at the bottom of the social ladder. On the economic front, colonialism left in its wake a system marked by extreme rural-urban disparity, with marginalized locations relying on noncompetitive subsistence economies that privileged landowners over peasants. Overreliance on goods like cocoa, sugarcane, and mining has continued to cripple the region’s economies over a century later.

These legacies—ideological and economic—translated into what would become a familiar pattern of political instability. As liberal governments came to power, paying lip service to the ideals of equality, they quickly had to confront economically harsh circumstances. Governments in the region also inherited a particular kind of state: weak in terms of its administrative and revenue-extracting apparatuses, while overly strong in terms of the coercive apparatus. The latter was itself partly the result of lengthy wars for independence, which in some cases lasted over two decades, as colonial rulers fought hard to retain their grip on power.

In short, the region’s new rulers faced a situation of economic hardship, weak states, strong armies, and a substantial gap between norms of equality and the reality of social discrimination. Political life was subject to few democratic checks, as patronage politics, corruption, and caudillo rule (with legendary strongmen at the helm of power) became commonplace. The stage was set for new elites to rely on the use of force to maintain order and stability, unleashing a vicious cycle of repression whose impact would be felt into the current millennium.

Trends and Cross-National Dynamics

Before we can attempt to explain why human rights are violated in Latin America, we need to understand the patterns of abuse that have characterized the region. These patterns have varied across countries and over time, as identified below. Due to the limited availability of quantitative data, most of the discussion focuses on rights violations after 1980; subsequent case studies nonetheless survey earlier periods.

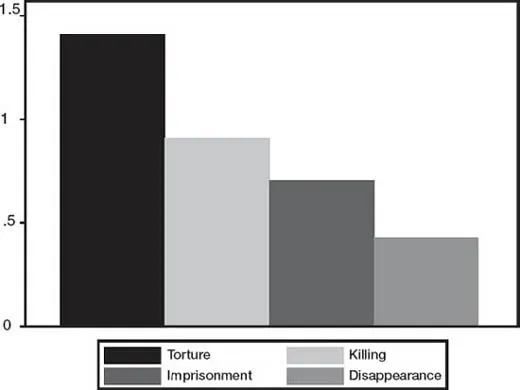

Differences in abuse over time. Since the 1980s, torture has been the most common type of personal integrity violation in Latin America, followed by extrajudicial killings, political imprisonment, and disappearances—in that order.2 It should also be noted that in the last quarter century, torture has been twice as common as political imprisonment, despite its strong global prohibition. Figure 2 illustrates these broad differences. Over time, moreover, these dynamics have shifted somewhat. Disappearances, in particular, have abated steadily, declining sixfold since the 1980s. In contrast, torture is still frequent (more than 50 cases per year) in almost half the region’s countries.

FIGURE 2. Human rights violations in Latin America: types and level of abuse, 1981–2006. Data from Cingranelli-Richards (CIRI) Human Rights Dataset (http://www.humanrightsdata.org). See note 2, p. 51 for levels of violation.

Subregional differences. State repression across Latin America seemed to sweep over the continent at the end of the twentieth century in three successive waves. R...