![]()

PART I

Phantom Phoenicians

![]()

CHAPTER 1

There Are No Camels in Lebanon

We start again, this time in 1946, and this time in Phoenicia itself. Three years after Lebanon gained its independence from France, the young Druze socialist politician Kamal Joumblatt gave a lecture in Arabic at the Cénacle libanais, a newly established forum for writers and politicians in Beirut, on “My Mission as a Member of Parliament.” His speech ended in an appeal to “hope and confidence,” as he reminded his listeners that their new state’s glorious history dated back to the ancient Phoenicians:

On this beautiful golden coast, which thousands of years ago witnessed the emergence of the first civic state, and the growth and diffusion of the first national idea, and the establishment of the first maritime empire, and the emergence of the first form of representative democratic government . . . in this rare spot in the world, where the sea and the mountain meet, embrace, and communicate . . . and in an internal national consciousness, as if Lebanon was self-conscious . . . in this country that has always been open to all the global intellectual currents of human civilization . . . in this ancient young country . . . which gave the world values, ideas, men, institutions, and glory, it is right for us to be optimistic.”1

Joumblatt’s approach to that crucial question for any young country—“Who are we?”—would have been very familiar to his listeners. “New Phoenicianism,” or the idea that the modern Lebanese were the inheritors of an ancient Phoenician legacy, had been a significant political and cultural movement in Lebanon since the breakup of the Ottoman Empire, and it is one that has lasted in some quarters to the present day. Its fundamental claim is that the nation of Lebanon is a timeless entity, with a distinctive character and culture determined by its distinctive geography, and a history going back to the city-states of the ancient Phoenicians, long before the arrival of the Arabs in the seventh century CE.

The movement was originally championed by Christians, and in particular Maronite Catholics, but Joumblatt’s words capture some of its most important aspects: on the one hand the glorification of the Phoenicians themselves, with an emphasis on their maritime achievements and their contributions to world civilization, and on the other the connections and parallels between them and the modern Lebanese, with an emphasis on the unique geography they shared. But Joumblatt does not just connect the Phoenicians with his new nation through history and geography; he makes them responsible for the idea of the nation itself, reflecting the underlying premise of this modern Phoenician rhetoric that the ancient Phoenicians too formed a coherent “people” or national community.

This chapter argues that the modern notion of the Phoenicians as a people with a shared history, culture, and identity—found in modern textbooks and scholarship as well as in postcolonial political rhetoric about Phoenician forebears—is the product of relatively recent European nationalist ideologies. I then turn in the rest of part 1 to the difficulties of reconciling this modern picture with the fragmentary ancient evidence. Lebanese Phoenicianism is a good place to start, a striking case study in the way in which we moderns can bend the ancient world to our own experiences, and to our nationalist assumptions and ideologies, including the notions that ethnic identities are natural, timeless facts and that ancient “nations” can and even should map onto nation-states.

THE YOUNG PHOENICIANS

The idea that the modern Lebanese were the inheritors of a Phoenician legacy was originally suggested by Lebanese scholars in the nineteenth century.2 The Maronite Catholic historian Tannus al-Shidyaq made the first explicit association between Phoenicia and Lebanon, and between the mountain and the sea, in his History of the Notables of Mount Lebanon (1859): his first chapter, on the borders and populations of Lebanon, discusses the location and population of Mount Lebanon and then those of the “Phoenician cities of Lebanon” (mudun lubnan al-finiqiyya).3 The idea that the Lebanese were in some sense Phoenician quickly gained traction in the early twentieth century among emigrant Lebanese communities in Egypt and the United States, aided by US government documents published in 1911 defining new immigrants from the Syrian coast not as Arabs, but as Christian descendants of the Phoenicians.4

It only became popular in Lebanon itself, however, in the aftermath of the First World War. In the context of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, which had held the region since the sixteenth century, and as the European powers carved up the Middle East, a loose collection of entrepreneurs, intellectuals, and political activists became fascinated by the idea of a link with their celebrated ancient predecessors. It was a largely urban, bourgeois, francophone grouping—one that saw the Phoenicians as natural merchants and champions of protocapitalist free enterprise.5 These “young Phoenicians” were not for the most part churchgoers, but they tended to have a Catholic education and perspective—most of them were themselves Maronites, and almost all, including Kamal Joumblatt, had attended the Jesuit Université Saint-Joseph in Beirut, where French missionaries had long encouraged the study of local pre-Islamic history and languages.6 They also relied to a significant degree on the work of French and francophone scholars, including those at the Université Saint-Joseph itself.7

Central to the ideology of the young Phoenicians was the conviction that Lebanon and the Lebanese were not Arab. They emphasized instead their metaphorical, spiritual, and sometimes even literal descent from much earlier inhabitants of their distinctive geographical space, where Mount Lebanon cuts off the coastal strip from the rest of Syria, a region they always characterized as peculiarly western or Mediterranean by contrast with the Arabs farther east: “there are no camels in Lebanon,” as the slogan goes.8 They argued among other things that the language spoken in Lebanon was influenced as much by the local ancient languages of Phoenician, Aramaic, and Syriac as by colloquial Arabic, and the poet Said Akl, who died in November 2014 at the age of 103, even invented an alphabet based on Latin rather than Arabic letters in which to write this “Lebanese” language.9 This rejection of Arab heritage was a long-lived phenomenon: as late as the 1950s, the widely respected Maronite historian Philip Hitti, who taught at Princeton and Harvard, noted that “according to anthropological researches, the prevailing type among the Lebanese—Maronites and Druzes—is the short-headed brachycephalic one . . . in striking contrast to the long-headed type prevailing among the Bedouins of the Syrian Desert and the North Arabians.”10

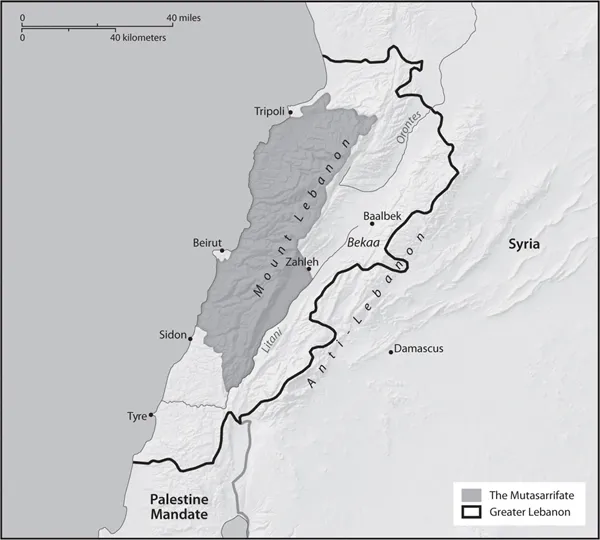

New Phoenicianism was closely connected with the broader, and also largely Maronite, struggle for a Lebanese state separate from Syria and the wider Arab world.11 The Phoenicians provided an attractive prototype and parallel for the new state as well as a convenient alternative to Arab origins, but they also played another very specific role in this Lebanist rhetoric. Within the Ottoman Empire, the area of Mount Lebanon itself had formed a majority Maronite Mutasarrifate or privileged administrative region since 1861, alongside a series of other Levantine provinces and subprovinces that included the coastal cities (fig. 1.1). With the whole of that empire on the negotiating table at Versailles in 1919, most “Lebanists” were arguing for the extension of the old Mutasarrifate to form a new state of “Greater Lebanon” under a French mandate, which would also include the traditionally Muslim areas of the Bekaa Valley to the east and the cities of Tripoli, Tyre, Sidon, and Beirut to the west. But to make the case for Greater Lebanon as the natural answer to the national question, the Lebanists had to tie together Mount Lebanon, the traditional home in modern times of both the Maronites and the Druze, and the Mediterranean coast, where the ancient Phoenicians built their cities. They did so by positing on the one hand a natural economic relationship between the mountain and

the sea, and on the other a long-standing historical connection between the Phoenicians and Maronites that preceded and then by-passed the Arabs: the Maronites had assimilated with the Phoenician coastal population on Mount Lebanon in the sixth century CE, converting them to Christianity along the way.12

1.1 The Ottoman Mutasarrifate of Mount Lebanon (1861), and Greater Lebanon under French Mandate (1920).

The neo-Phoenician movement coalesced around the short-lived journal La revue phénicienne, published for just four issues in 1919, and strongly Lebanist in its politics. The first issue appeared in July, immediately after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, and at a stage when the future of Lebanon itself and its future relationship to both Syria and France were still quite unclear. The contributors were for the most part Beiruti businessmen,13 and much of the issue was devoted to the economy: the financial case for Greater or “natural” Lebanon, the country’s resources, the hotel and tobacco industries, the problems of small businesses, and the reprovisioning of Beirut. Plenty of space was given to political issues as well: the advantages of a French mandate, the disadvantages of the American King-Crane Commission sent to investigate local attitudes to the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, and the proper basis of a state. There was also local history, literature, literary commentary, and a diatribe by a medical professor against the corset.

Naturally, the Phoenicians were also present. The issue begins with an introductory page attributed to “L’histoire,” presumably written by the editor, Charles Corm, outlining the Phoenicians’ history, character, and achievements. They were above all men of the sea, sailing as far as Great Britain; liberal, peaceful; bringing the world civilization, commerce, and industry. Although the author understands that the city-states of the “land” (contrée) of Phoenicia were politically autonomous, he presents them as united not only by a common culture but by a common proto-monotheism and unusual rituals: “they all worshipped a higher Divinity to whom they sacrificed human victims.”14 In another article, Jacques Tabet goes further, describing la Phénicie as a “country” (pays) and suggesting that in the tenth century the rest of “the Phoenician people” (le peuple phénicien) had recognized the supremacy of King Abibaal of Tyre—about whom we in fact know barely anything beyond his name—whereby he “brought about the political unification of Phoenicia.”15 The historical importance of this entirely speculative point becomes clear in the essay on the King-Crane Commission signed by “Caf Remime” (that is, the letters KRM, or “Corm” in Phoenician script): “we want this nation [of Lebanon] because it has always come first in all the pages of our history.”16

A PHOENICIAN NATION

Phoenicianism was by no means the only nationalist movement in the early-twentieth-century Middle East to identify with the great civilizations of the past, and through them with the Mediterranean and the West. Other examples include Pharaonism in Egypt, Assyrianism and Arameanism in Syria, and Canaanism in Palestine, whose adherents looked back to a “Phoenician-Hebrew” Mediterranean civilization dating to the time of King David and King Solomon that colonized the west, a model that was used both for and against Zionism.17 Furthermore, in Lebanon itself supporters of a “Greater Syria” rather than an independent Lebanon could also appeal to the Canaanites as forebears, and even as the inventors of national sentiments,18 and there were also Christian as well as Muslim supporters of an even larger Arab nationalism who argued, with the Greek historian Herodotus, that the Phoenicians were immigrants from the Arabian peninsula, and therefore that they actually provided Lebanon with an Arab heritage.19

Why was ancient history so important to these modern political movements? In all these cases, not only nation-states but national identities of any kind were a recent import from Europe in a region where polities had previously taken quite different forms and where “identity realms were more local and limited: the family, village, chur...