![]()

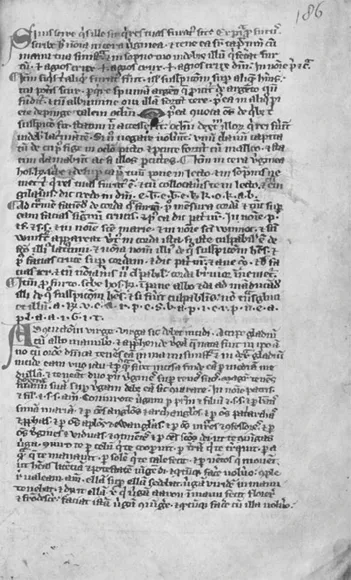

3 Details of an ‘experiment’ to identify thieves, from a late 13th-century medical treatise.

CHAPTER ONE

Predicting the Future and Healing the Sick: Magic, Science and the Natural World

Experiments for stolen goods: If you want to know who it is who has stolen your things, write these names on virgin wax and hold them above your head with your left hand, and in your sleep you will see the person who has committed the theft: ‘+ agios crux + agios crux + agios crux domini. In the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.’ [agios is Greek for ‘holy’; crux domini Latin for ‘cross of the Lord’.] Likewise if someone has stolen something from you or you suspect them of something, you will be able to know in this way. Take silver scum, which is thrown up from silver when it is poured, and grind it vigorously with egg white. Afterwards paint an eye like this [see illus. 3] on a wall. Afterwards call together everyone whom you suspect. As soon as they approach, you will see the guilty people’s right eyes weeping.1

These two methods for identifying a thief were copied at the end of a collection of medical treatises in the late thirteenth century, alongside many other ‘experiments’: how to cut a stick in half and join it together again, how to put your hand into boiling water unharmed, how to restore harmony to quarrelling friends, prevent your enemies from acting against you or excite lust in a woman. Some of these may have been used primarily to entertain, especially the ones for tricks such as cutting and joining the stick. But identifying thieves was a serious matter, and divination which aimed to uncover this kind of hidden information or predict the future is one of the forms of magic which medieval English clergy who wrote manuals for pastoral care, preaching and confession discussed most often and in the most detail.

The scribe who copied these directions did not call them ‘magic’. Instead he called them ‘experiments,’ meaning phenomena which could not be explained by medieval science but which had been proven to work. In contrast to modern experimental science, however, medieval ‘experiments’ did not involve rigorous testing and it was often enough that a respectable earlier writer claimed they worked. Experiments such as these were generally assumed to work because of natural forces but medieval writers did not know exactly how they worked. This posed a problem because if the forces behind experiments were not understood, it was always possible they were not natural at all and instead worked because of demons: in other words, they might be magic. These ‘experiments’ to identify thieves therefore point to a crucial problem for educated medieval clergy: how do you distinguish between legitimate ways of manipulating natural forces and magic? Or in modern terms, how do you draw a line between magic and science?

Medieval churchmen faced this problem when they thought about two kinds of magic in particular: divination and healing. Both were discussed in detail by pastoral manuals and educated clergy often paid far more attention to them than to other kinds of magic precisely because in these cases it was difficult to draw firm lines between religion, magic and science. It was clear that some ways of predicting the future relied on the observation of cause and effect, and many healing practices were also believed to work purely by natural means, by affecting the balance of humours in the body. (The humours were four substances thought to be found in the body, and ancient and medieval medical writers believed the balance between them determined health and illness.) The existence of these natural methods of prediction and healing meant there was much scope to argue about what was legitimate and what was not. Educated clergy saw it as their job to define and police the boundaries, and to make sure legitimate medicine and forecasting did not shade into demonic magic.

This task fitted in well with some wider currents of thought in medieval Europe. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, ancient Greek scientific works, especially those of Aristotle, were being translated into Latin from Arabic and from the original Greek. These treatises prompted medieval intellectuals to study the natural world in greater depth, and also to think more precisely about what counted as ‘natural’ and what as ‘supernatural’.2 But this was not just a theoretical issue to be debated by a small group of educated men. Pastoral writing on magic shows that the question of where the natural world ended and magic began was relevant to everyone, because at some point in their lives almost everyone would become ill, have something stolen, become anxious about the future or want to secure good fortune. Deciding which ways of responding to these problems were natural and which were magical was therefore an important pastoral issue.

Interpreting the Universe

Many ways of predicting the future were based on observing the natural world and the seemingly random events which occurred in everyday life. Almost anything was potentially meaningful, from the motions of the stars, to the crowing of a bird, to meeting a certain kind of person on the road, as in the story of Master G and William the monk. Interpreting these signs was not necessarily seen as magic. It was widely believed that God sometimes used the natural world to communicate with mankind and so medieval chroniclers regularly noted comets, eclipses and other unusual natural phenomena alongside more ordinary events. They were well aware that some of these phenomena (such as eclipses) had predictable physical causes but despite this they also viewed them as signs from God which carried a wider meaning.3 Even if God was not involved, it was widely recognized that some future events could be deduced simply by observation. Anyone could predict the weather with a fair degree of success if they saw grey clouds overhead, and people with specialist knowledge could do much more. For example, astrologers claimed to be able to offer long-term weather forecasts and many treatises explaining how to do this survive from across medieval Europe.4 Doctors, too, could predict the future within their own field of expertise. Medical prognosis went back to ancient times but it took on a new significance in the Middle Ages. In medieval Christianity it was important to know whether you were dying so that you could die a ‘good death’: one where you had time to confess your sins and receive the last rites.5

Late medieval English churchmen never suggested that noting portents such as comets, weather forecasting or medical prognosis constituted magic. Quite the opposite: they stressed they were not. But beyond these recognized ways of interpreting the natural world, meanings were attached to a wide range of other natural phenomena and chance events which churchmen found far more difficult to accept. Medieval English pastoral writers gave many examples of these, sometimes adding new details to what they found in earlier sources. For example Thomas of Chobham, an administrator at Salisbury Cathedral who wrote a Summa for Confessors shortly after 1215 which circulated widely in medieval England, criticized people who believed that if a dog howled in a house, someone in the house would soon become ill or die.6 More than a century later he was quoted by Ranulph Higden, a monk from Chester, who added another belief: if a magpie crowed on the roof of a house a visitor would soon arrive.7 Then in around 1400 Robert Rypon, a monk of Durham Cathedral Priory, complained in a sermon that ‘if someone finds a horseshoe or iron key he says (as the common people do) “I shall be well today.”’8 Probably there were many similar beliefs and churchmen could always add new details if they wished.

What was wrong with believing in these omens? What was the difference between predicting the weather from grey clouds and predicting a visitor from a magpie on the roof? As early as the fourth century St Augustine had discussed the issue at length and his comments had a great influence on how later churchmen thought about divination. Augustine argued forcefully that omens such as these had no real connection with the events they portended. Instead he poked fun at people who believed in these ‘utterly futile practices’: quoting the Roman writer Cato, he pointed out that it was not an omen if mice nibbled your slippers; but if the slippers nibbled the mice, then you would know something strange was going on. He also denounced the use of astrology to predict people’s futures for the same reason: the stars had no real connection with the events astrologers claimed to predict. After all, twins born at almost the same time could go on to lead significantly different lives so what was the use of making predictions based on the time a person was born? In the twelfth century Augustine’s comments were summarized in the Decretum of Gratian, one of the most influential canon law textbooks, so they were known to many later educated clergy.9

Augustine used mockery to attack omens but he also argued they were a serious problem because demons might use people’s superstitions to their own advantage. If demons saw people observing omens then they might intervene to make those omens come true, in order to distract the unwary from their faith in God: and that was why believing in omens was magic, just as other forms of trafficking with demons (knowingly or unwittingly) were.10 Pastoral writers in medieval England knew their Augustine and they treated omens with the same combination of mockery and seriousness. Thus an exemplum, or moral story, told by the fourteenth-century friar John Bromyard ridiculed a belief we have already encountered in Peter of Blois’ letter on omens: the idea that meeting a monk or priest on the road signified bad luck on the journey. In this story a priest became annoyed because when he passed a woman on the road, she crossed herself to ward off any misfortune that might come to her after experiencing such a bad omen. The priest responded by pushing her into a ditch, to show her that believing in omens was much more dangerous than meeting a priest!11 But putting your faith in omens could have much more serious consequences. Another exemplum which was widely copied told of a woman who heard a cuckoo cry five times on May Day. She took this as an omen that she had five years left to live and so when she fell ill soon afterwards she refused to make confession, assuming she would recover. Since this was a moral story she died shortly afterwards without receiving the last rites – a warning to others who might be tempted to trust in omens.12

Counting bird cries was simple, cheap and did not require education and so almost anyone might believe in omens like these, but a few pastoral writers also expressed concerns about a more academic way of interpreting the natural world: astrology. Astrology was a specialist skill. The practitioner had to read astrological texts, which were often in Latin, and know the positions of the planets and enough arithmetic to calculate horoscopes effectively. The level of technical knowledge involved is shown by surviving medieval astrological calculations such as the ones left by the astrologer and medical practitioner Richard Trewythian, who lived in fifteenth-century London (illus. 4).13 Some kinds of astrology were accepted as natural, since many medieval people believed the stars could affect the natural world and even the human body: for example, the University of Paris’s medical faculty pointed to a malign conjunction of planets as one of the causes of the Black Death in 1348.14 But not all kinds of astrology were accepted as purely natural, and despite its learned trappings Augustine had denounced astrology as false and magical, just as omens were.

Because astrology was restricted to people with education and access to books, it was less of a priority for many churchmen than were more widespread beliefs about omens, and many pastoral manuals did not mention it. Nevertheless, a few did, including some which were widely read in medieval England. When they did so they took the same approach as they did to other forms of divination, focusing on whether astrology could predict the future by natural means. In the process they took pains to distinguish between legitimate and illicit kinds of astrology, in a way that Augustine had not. Their reasoning was explained in one of the most widely circulated medieval pastoral manuals, the Summa for Confessors written by the German Dominican friar John of Freiburg in 1297–8:

If someone employs careful observation of the stars to predict future accidental or chance events, or even to predict people’s future actions with certainty, this will proceed from a false and vain opinion, and therefore is mixed up with the opinion of a demon, and so it will be superstitious and illicit divination. But if someone employs observation of the stars to predict future things which are caused by the heavenly bodies, such as droughts and rainfall and other things of this kind, that will not be illicit divination.15

In other words astrology could genuinely predict certain things and it became magic only when it strayed beyond this to predict people’s future actions. These could not be predicted because God had given mankind free will, which gave people the power to overrule the stars. Here John was drawing on the ideas developed slightly earlier by the theologian Thomas Aquinas, but he also reflected a more widespread consensus among many intellectuals about the possibilities and limits of astrology.16

In theory, then, it was clear why omens and the use of astrology to predict people’s actions were magic and why weather forecasting, medical prognosis and other forms of astrology were not. With omens and astrology, the signs that people observed had no genuine connection with the events they predicted, but in prognosis and weather forecasting, the prediction was based purely on the observation of natural processes. But things were not always so clear-cut. In practice many people seem to have accepted as natural a wider variety of ways of predicting the future than the pastoral writers did; or at least they do not seem to have seen them as very wrong. The London astrologer Richard Trewythian, for example, used astrology to predict a wide range of events and uncover information about the present.17 Most of his predictions related to the natural world, such as forecasting the weather or the quality of that year’s harvest; or were predictions of general events such as wars, but some were more questionable. For example, he seems to have asked about the outcome of some political events in the 1450s. This was potentially a dangerous activity because it could, in the wrong circumstances, lead to accusations of treason: it was deemed to be a short step from predicting the king’s death to trying to bring it about. In other cases Trewythian asked about individual people’s actions: would a missing person return? Who had committed a theft and would the stolen goods be found? If a strict pastoral writer had examined what Trewythian was doing, he would have found some of these predictions difficult to explain as natural. However, there is no evidence that either Trewythian or his clients felt such qualms. This was true of some clergy as well as laypeople. One of Trewythian’s horoscopes was drawn up f...