eBook - ePub

Active Citizenship and Community Learning

Carol Packham

This is a test

- 168 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Active Citizenship and Community Learning

Carol Packham

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This book explores the role of the worker in facilitating participation, learning and active engagement within communities.

Focusing on recent initiatives to strengthen citizen and community engagement, it provides guidance, frameworks and activities to help in work with community members, either as different types of volunteers or as part of self-help groups. Setting community work as an educational process, the book also highlights dilemmas arising from possible interventions and gives strategies for reflective, effective practice.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Active Citizenship and Community Learning un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Active Citizenship and Community Learning de Carol Packham en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Sciences sociales y Travail social. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Chapter 1

The context of active

citizenship and community

learning

This book is written as a contribution to the ongoing reflections of Youth and Community Workers regarding their relationship to the state and those with whom they work. The dilemmas evident in the book show the tensions between communities, who on the one hand are being called on to participate and have a voice in government processes from neighbourhood level up, whilst on the other are expected to voluntarily become part of processes of control, surveillance and welfare, often within communities that are already disadvantaged and excluded.

I make the case that Youth and Community Workers have an important role to enable community members to reflect on their experience in spaces for critical dialogue, which can bring about self directed change. I argue that critical, informal education based on Freirian approaches can be carried out with all types of volunteers, from those involved for primarily individual benefit to community activists, and that this is an important function of community learning.

This book draws on my experience as a Youth and Community Worker, volunteer and community activist in Manchester, and course leader of the BA in Youth and Community Work at Manchester Metropolitan University. It was brought together as the result of my involvement with the Home Office pilot Active Learning for Active Citizenship programme that ran from 2004 to 2006, and which contributed to the primary research for my Doctor of Education thesis. This book is therefore illustrated with a range of examples from these areas of ongoing practice.

The book provides exercises to help you think about the key themes of each chapter. They can be carried out individually or as part of a group, in line with the process of informal education. Many ask you to reflect on your own experience. The initial chapters give the social policy and theoretical context of our work, leading to specific chapters on work with different types of volunteers and carrying out community learning. The final chapters on enabling participation, inclusive, representative and reflective practice, although generally relevant raise particular issues in relation to citizenship and action.

The social policy context

Why this book, now? People have been involved in all types of voluntary activity throughout human existence; all involvement was voluntary before the establishment of paid employment. By the industrial revolution, those involved on a voluntary basis in Britain and her colonies were predominantly engaged in philanthropic activity to moralize, save or control those that they deemed to be a risk or at risk. Others were involved in self help activities within their communities or work places, and would most probably have been regarded as political agitators and viewed as a threat.

Recent interest in voluntary community engagement had stemmed from a variety of themes:

- Voluntary work experience can increase the range of skills and knowledge of a volunteer and so contribute to their future employability.

- Engaging in a voluntary capacity within communities and neighbourhoods contributes to social and individual well being.

- Social well being contributes towards social cohesion and a reduction in crime, antisocial behaviour, terrorism and extremism.

- Engagement in voluntary activity as part of a group can be an empowering and transformational experience leading to change and improvement (e.g. as part of a pressure or campaign group).

- Voluntary activity, particularly at the neighbourhood level, can improve the delivery of services and impact of initiatives at a local level (e.g. through community wardens).

- Active involvement can increase civic and civil engagement, and improve levels of involvement in governance, e.g. ‘Citizens are now politically active in new ways and the challenge is to connect their activity to formal politics’ (Goldsmith, 2008, p.3).

- Engagement of citizens (e.g. service users) in policy making can enable more effective and efficient delivery of services.

- Enforced community involvement can repay or contribute to society and ‘do good’, for example work undertaken by students, refugees and asylum seekers, and those serving community sentences for non-serious criminal offences.

- Volunteering is viewed as representing a step towards the achievement of full citizenship.

Voluntary involvement can therefore be seen to have moved beyond merely ‘doing good’ to being viewed as a means of developing good governance and community cohesion, as well as enhancing individual employability.

Garratt and Piper (2008), when discussing the development of volunteering initiatives, state that:

Since 1997, volunteering as a principle and practice has been promoted in a range of related areas of policy . . . volunteering may indeed extend the social and occupational experience and range of young people. It may also generate personal satisfaction, from helping others and acquiring self-knowledge. Through government funded schemes to encourage and channel voluntary activity, voluntary organizations of all sizes and types may achieve their social, educational or environmental aims. For all that, particular characteristics of this enthusiasm for volunteering suggest that the success of these initiatives may be limited, and may have unintended (and often unhelpful) consequences . . . voluntary work must be voluntary, and the current enthusiasm for ensuring that it occurs, obscures the fact that it is something that people cannot be made or paid to do. Being told that voluntary work is good for you or for the community will not ensure participation unless there is the prior capacity, drive, or motivation to become involved. (Garratt and Piper, 2008, p.56)

Piper indicates not all volunteering schemes are voluntary, and as a result may be counterproductive. Additionally, not all individuals are equally able to participate. Social exclusion and the distribution of power affect the ability to become involved citizens, and so stifle the ability of some to reach their own and their community’s potential. The government is attempting to redress this through the Communities in Control White Paper (DCLG, 2008) and a range of other measures to enforce ‘the duty’ to involve citizens in decision making.

Alongside this has been an increased emphasis on citizenship, and voluntary and active citizenship as being a reflection of an individual’s duty and obligations to the state. Recent government initiatives have therefore been influenced by a commitment to:

- better enable local people to hold service providers to account;

- place a duty on public bodies to involve local people in major decisions;

- assess the merits of giving local communities the ability to apply for devolved or delegated budgets. (Governance of Britain, 2007, pp.7–8)

Voluntary involvement and citizenship

The British government approach defines citizenship as a state that has to be acquired or granted, based on your commitment to the norms of society. This is evident in the Goldsmith Citizenship Review, which talks of ‘the duty of allegiance owed by citizens to the UK . . . citizenship should be seen as the package of rights and responsibilities which demonstrate the tie between a person and a country (2008, p.1). This approach is different from that of citizenship being a status which is conferred on all people who live within that society and assumed as a right from birth.

The Citizenship Review identifies what the government can do to ‘enhance the bond of citizenship’ that we feel as shared citizens. The measures outlined in the review are aimed to ‘promote a shared sense of belonging and may encourage citizens to participate more in society’ (Goldsmith, 2008, p.7). These measures include: school citizenship manifestos and portfolios detailing work carried out with the community; reduced university tuition fees for young people who volunteer; citizenship ceremonies for young people and new citizens; and deliberation days to encourage debate before elections (Goldsmith, 2008, p.7).

From the above discussion it can be seen that there is increasing government attention being paid to what has historically been a private, individual matter of how you spend your ‘free’ time. The successful involvement of individuals within their communities and local decision making processes are now viewed as essential elements for cohesive communities and effective service delivery. It is therefore important that Youth and Community Workers consider how we relate to these government agendas, and consider the implications for the application of our principles and practice.

Citizenship and action

Enabling people to be active and take action within their communities has been the focus of community workers since the growth of community development in the 1960s in Britain. The first government-led initiatives in community capacity building were through the local authority based Community Development Projects, which proved too radical and challenging to the institutions that were funding them, and the projects were quickly disbanded. During the 1980s the Conservative government’s approach denied the importance of community as ‘political developments were centred on individuals and families pursing their own interests in the context of the market’ (Woodd, 2007, p.8).

With the arrival of the New Labour government in 1997, social policy became influenced by views that the community was important both for the well being and solidarity of its members and for society as a whole. Based on the theories of communitarianism and the development of social capital, the then Home Secretary David Blunkett emphasized the concept of active citizenship and the ‘idea that the freedom of citizens can only be truly realized if they are enabled to participate constructively in the decisions which shape their lives’ (Woodd, 2007, p.8).

ACTIVITY 1.1

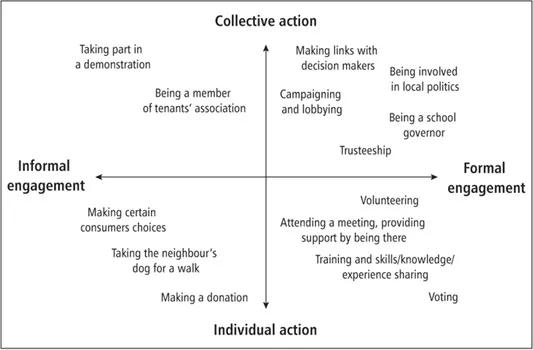

Think about the ways that you choose to help or benefit other people that you are not paid to undertake; divide these into:

- activities that you may do on your own as an individual;

- activities that you carry out as part of a group;

- those that are part of informal arrangements;

- those that are part of formal structures.

These categories can be used as the basis for identifying different types of active citizen involvement and are shown in the figure below. They will be discussed in Chapter 4.

From 1997 a raft of policy documents and initiatives were developed working towards civil renewal, including the introduction of the citizenship curriculum. David Blunkett identified the key government themes as being ‘a shared belief in the power of education to enrich the minds of citizens, a commitment to develop a mutually supportive relationship amongst the members of a democratic community and a determination to strengthen citizens’ role in shaping the public realm’ (Home Office, 2003, p.3). He further identified the government role in trying to achieve these by stating ‘instead of standing back and letting go of the values of solidarity, mutuality and democratic self determination, government – both central and local – has a vital role to play in strengthening community life and renewing civic involvement (Home Office, 2003, p.4). In the Home Office pamphlet Active Citizens, Strong Communities – Progressing Civil Renewal (2003) he made the case that this was an essential task for the development of strong communities and a way of avoiding a fragmented society.

Active citizens have therefore become a central element of government attempts to build community cohesion, devolve power to a community level, engage people in democratic processes, and help identify and meet local needs. Individuals may be active in a number of ways, as you would have identified through the above task. On an individual level this may be involvement in political processes through voting and by helping as a volunteer. Individuals can also participate through existing, formed structures, such as serving as school governors or on management committees of voluntary organizations. They may also participate in natural groups, such as campaigning groups at a local, national and global level, ‘actively challenging unequal relations of power, promoting social solidarity and social justice, both locally and beyond, taking account of the global context’ (Take Part, 2006, p.13).

The figure below shows different types of citizenship involvement, illustrating the connections between individual and collective actions and formal and formal engagement (based on NCVO, 2005).

Figure 1.1 Citizen involvement (From www.takepart.org. p.13)

It is necessary for Youth and Community Workers to consider the different types of involvement, ranging from volunteers to active citizens and community activists, and our role in supporting and enabling this activity, and the learning processes this necessitates. The implications for Youth and Community Workers are discussed throughout this book.

Active Learning for Active Citizenship (ALAC)

The increased recognition of citizen activities and the involvement of community members at a community and group level has resulted in attention being paid to how they are tr...

Índice

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The context of active citizenship and community learning

- 2 The role of the Youth and Community Worker as informal educator

- 3 Civil and civic involvement and ‘active citizens’

- 4 Volunteers and active citizens

- 5 The role of the Youth and Community Worker in relation to volunteers

- 6 Enabling participation in communities

- 7 Inclusive and representative practice

- 8 Community based learning: learning by doing

- 9 The effective practitioner

- 10 Taking the work forward

- Glossary

- Index

Estilos de citas para Active Citizenship and Community Learning

APA 6 Citation

Packham, C. (2008). Active Citizenship and Community Learning (1st ed.). SAGE Publications. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/861398/active-citizenship-and-community-learning-pdf (Original work published 2008)

Chicago Citation

Packham, Carol. (2008) 2008. Active Citizenship and Community Learning. 1st ed. SAGE Publications. https://www.perlego.com/book/861398/active-citizenship-and-community-learning-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Packham, C. (2008) Active Citizenship and Community Learning. 1st edn. SAGE Publications. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/861398/active-citizenship-and-community-learning-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Packham, Carol. Active Citizenship and Community Learning. 1st ed. SAGE Publications, 2008. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.