eBook - ePub

AFA6 Our Sphere of Influence

Australian Foreign Affairs; Issue 6

Jonathan Pearlman, Jonathan Pearlman

This is a test

- 128 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

AFA6 Our Sphere of Influence

Australian Foreign Affairs; Issue 6

Jonathan Pearlman, Jonathan Pearlman

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

"The uncomfortable reality is that preserving an exclusive sphere of influence in the South Pacific is not going to be possible against a regional power that is far stronger than any we have ever confronted, or even contemplated." HUGH WHITEThe sixth issue of Australian Foreign Affairs examines Australia's struggle to retain influence among its Pacific island neighbours as foreign powers play a greater role and as small nations brace for the impacts of climate change. Our Sphere of Influence explores the security challenges facing nations in the southern Pacific and whether Australia will need new approaches to secure its relations and interests.

- Hugh White argues that Australia will be unable to keep China out of the Pacific and must urgently renew its defences.

- Jenny Hayward-Jones examines whether Scott Morrison's Pacific "step-up" can reverse Canberra's declining diplomatic influence.

- Katerina Teaiwa explores how Australia's climate change policy undermines ties with its island neighbours.

- Sean Dorney reports from inside the forgotten Australian colony of Papua New Guinea.

- Euan Graham proposes how to address Australia's knowledge gaps about the Chinese leadership and military.

- Elizabeth Becker reflects on the unique challenges for female foreign correspondents.

PLUS Correspondence on AFA5: Are We Asian Yet? from Clive Hamilton, Barry Li and Linda Jaivin.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es AFA6 Our Sphere of Influence un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a AFA6 Our Sphere of Influence de Jonathan Pearlman, Jonathan Pearlman en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Politique et relations internationales y Géopolitique. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

GéopolitiqueReviews

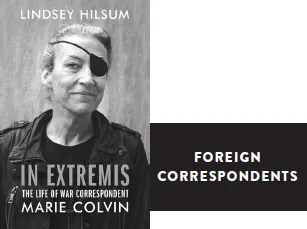

FEATURE REVIEW

In Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin

Lindsey Hilsum

Vintage

The Super Bowl professional football championship is the single biggest sporting event in America. The television audience is enormous – some 100 million people watched the game this year – allowing the network to charge corporations $10 million a minute to air their advertisements. These ads famously try to convince the captive audience, through wit or sentimentality, to buy the beer or the car, the food or the skin cream, for sale.

This year, one of those ads broke the mould. The Washington Post paid for a sober one-minute advertisement that wasn’t selling anything. Instead, it extolled the virtue of a free press – in general, not just in relation to the iconic newspaper of the American capital.

That is how treacherous the mood has become in the United States. The president calls journalists “enemies of the people” and refers to any critical reporting as “fake news”. Trump’s vicious attacks are eroding confidence in the press, though its freedom is enshrined in the Constitution. And his remarks are cited by authoritarian leaders – such as Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines and Hun Sen of Cambodia – who are attempting to solidify their power by eliminating an independent media.

So the Washington Post ad was a clear proclamation that the press refused to be bullied. Narrating over clips from World War II through to the civil rights marches and to the moon landing, actor Tom Hanks reminds the audience, “When we go to war, when we exercise our rights or when our nation is threatened, there is someone to gather the facts, to bring you the story no matter the cost.”

At that moment, photographs of three journalists slowly pass across the screen. All three have been murdered for reporting the truth. Their very lives have been the “cost” of bringing their stories to the public.

One reporter has sleek golden hair and wears a black eye patch. She looked gamely into the camera with a half-smile, clearly a figure with pizzazz. She is Marie Colvin, the American war correspondent who was murdered by Syrian soldiers on orders from the government of Bashar al-Assad. In this image she was reporting from the besieged city of Homs, her pieces showing conclusively that government soldiers were systematically attacking civilians. By the Syrian government’s calculation, Colvin had to be silenced. In killing her, Assad’s army broke the international rules of war.

But Colvin is much more than a martyr. She is a striking symbol of the urgency and seriousness needed at this perilous moment to protect a society’s right to an independent press. Colvin’s articles dissected complicated problems and their consequences in places and circumstances where few other reporters ventured. Her life epitomised the unbearable hazards a correspondent often faces and the trauma and pain that spills over to their personal lives. Colvin’s life and work are both worth remembering – not only for her contribution to journalism, but as a rebuttal to the toxic slurs uttered and illegal arrests made to quiet the free press.

In Extremis tells Colvin’s fully lived story. This honest, often unsparing biography is written by Lindsey Hilsum, a friend and colleague, who reveals how such a complicated, courageous woman became one of the world’s best war correspondents, and one of the most damaged.

Hilsum uses Colvin’s diaries and letters to show how this Yale-educated American working for London’s Sunday Times trained herself to accept the high cost of covering wars, to risk her life repeatedly and to absorb the emotional impact of all that senseless inhumanity in order to write articles that went beyond the stilted press releases and showed the damning truth.

Colvin grew to look the part. Her eye patch came after she lost an eye reporting on starvation in embattled Sri Lanka. Her elegance, even in the grotty precincts of combat, spoke to her refusal to be less than human even as the sacrifices of her profession upended her personal life. And her articles – above all, her articles – underline her singular, almost spiritual belief that her role was to write about the civilian victims of brutal wars. In her last interview, hours before she was murdered, she said that she had just witnessed a baby die.

Colvin came of age at a time when women had broken through many social barriers and were welcomed on foreign news staffs and assigned some of the roughest stories. The Middle East was her sweet spot. She went from Basra, Iraq, to Beirut, Lebanon, in her first month at The Sunday Times. She conducted exclusive interviews with Libyan leader Muamar al-Gathafi and Yasser Arafat of the Palestinian Liberation Organization.

Colvin established her own style of reportage, staying on the front lines longer than others, often ignoring the hardware of war to focus on the bloody consequences for civilians caught in crossfire and targeted attacks. This is from her article datelined Beirut, 5 April 1987: “She lay where she had fallen, face down on the dirt path leading out of Bourj el Baranjneh. Haji Achmed Ali, 22, crumpled as the snipers’ bullets hit her in the face and stomach. She had tried to cross the no man’s land between the Palestinian camp and the Amal militiamen besieging it to buy food for her family.” Only a reporter risking the same fate could have written that powerful paragraph.

Colvin went on to the muddy killing fields of Bosnia. She made news herself in East Timor, where she refused to heed official warnings and stayed with refugees in a United Nations camp while Indonesian militia moved in to kill them. Her articles and interviews, along with those of two other women reporters who stayed, helped lift the siege.

Colvin was on a tear. She went next to the frozen frontlines of Chechnya, and then to Sri Lanka. The rebel Tamil Tigers had been fighting for over a decade to establish a separate homeland from the dominant Buddhist Sri Lankans. Colvin was promised an exclusive interview with the rebel leader and a first-hand account of the children starving because of boycotts in the war.

By now she was openly arguing with her editors when they challenged the wisdom of her crossing into yet another risky rebel territory. She would have none of it. But in Sri Lanka the biggest story she wrote was how she lost her eye in crossfire. “Why do I cover wars?” she wrote afterwards. “I did not set out to be a war correspondent. It has always seemed to me that what I write about is humanity in extremis, pushed to the unendurable, and it is important to tell people what really happens in wars – declared and undeclared.”

She railed against the routine praise for her as a woman war correspondent. Men were known simply as war correspondents. To her mind, being female should make no difference.

That may be true, but she was learning that as a woman she would suffer differently from her male colleagues. Underneath the boldness, she was cracking. Her private life was a near-shambles. Both her marriages failed as her husbands complained she was away too often and unable to be monogamous. Due to these separations, she lost the chance to have the children she thought she wanted. She was beginning to tally up the price of being a woman in her field.

Like many war correspondents, Colvin suffered severe post-traumatic stress disorder after years of witnessing carnage on battlefields, of feeling fear and adrenaline mount as she waited for the next round of attacks. After losing her eye in Sri Lanka, she nearly became catatonic. She suffered waking nightmares. She was housebound, prone to shaking. She drank far too much and was endlessly questioning whether it was all worth it.

Fortunately, her employers recognised her distress and eventually convinced her to check into a clinic. Hilsum, a respected foreign correspondent herself, carefully dissects how Colvin resisted coddling but finally accepted treatment to lift her from profound depression and show her how to cope with those memories that would never disappear.

Several years later, Colvin addressed the general predicament of her tribe. “We always have to ask ourselves whether the level of risk is worth the story. What is bravery, and what is bravado?”

Colvin found her answer in an idealised version of Martha Gelhorn, the rare woman who succeeded as a World War II–era war correspondent – and came with more than a whiff of glamour, as a former wife of Ernest Hemingway.

At first glance, Gelhorn is an odd choice as a role model. She was working in a time when women weren’t allowed near most battlefields. Women didn’t become combat reporters in numbers until the Vietnam War. But Gelhorn made her reputation covering what she called the face of war, the brutal images that “are the strongest argument against war”. Gelhorn was a fellow spirit from another era – who also watched her personal life fall apart in the pursuit of a “crusade on behalf of those without a voice in society”.

When Syrian intelligence finally pinpointed Colvin’s hiding place in Homs in 2012 and targeted her and her colleagues, she had negotiated some of her challenges and was determined to carry on her work.

Wa’el al-Omar, her guide in Homs, was one of the last people to see her alive. “I knew her for a short period, but it was a time of life or death,” he said. “She dreamed of being a voice for the weak, and of a place where war doesn’t affect civilians. She wasn’t childish or naïve, but she was idealistic. She was a dreamer.”

What better moment than now to appreciate everything required to write those articles from war, to translate those intense moments of humanity in extremis? This remarkable and sensitive biography is a rebuttal to every bully or coward who accuses a journalist like Colvin of being an “enemy of the people”, to every frightened politician who denounces independent journalism as “fake news”.

Last year alone, sixty-three journalists were killed doing their jobs around the world; half of them were deliberately targeted, according to Reporters Without Borders. For the first time, the United States was listed as one of the five most dangerous countries to be a journalist, joining India and Mexico, where reporters were also killed in rampages. A.G. Sulzberger, the publisher of The New York Times, asked Trump in person this year to stop his anti-press ravings. The effects, he said “are being felt all over the world, including [by] folks who are literally putting their lives on the line to report the truth”.

The president made no such commitment.

This year, an American court found the Syrian government guilty of murdering Colvin by targeted shelling – a reminder that the messenger relaying these truths often suffers as much as the soldier fighting the wars.

Elizabeth Becker

Common Enemies: Crime, Policy and Politics in Australia–Indonesia Relations

Michael McKenzie

Oxford University Press

The Mexicans have a saying that perfectly illustrates the nature of their neighbourhood: So far from God, so close to the United States.

Closer to home, there is a whole body of literature about two other odd neighbours, Indonesia and Australia. In recent decades, a common thesis is that this couple represents a “relationship in recurrent crisis” – a claim based on controversies over issues such as beef, boats, spying and treatment of drug mules and Indonesian fishermen.

But crisis was not the dominant feeling during my five years (from 2005 to 2010) as ambassador in Jakarta. The two countries had fallings-out during those years over the granting of asylum to Papuan Indonesians, New South Wales’ disgraceful treatment of the Jakarta governor during an official visit, and various issues relating to people smuggling. There were certainly moments of bad blood and bruised feelings. On the other hand, there were interactions that generated quite different responses, notably the Australian assistance following the Aceh tsunami in December 2004. It was also a period of joint work in a range of areas, including agriculture, health, regional initiatives and education in eastern Indonesia – the sorts of things that do not often attract headlines.

In Common Enemies, Michael McKenzie deals with developments in the handling of major law-enforcement issues between the two countries since the 1970s. He writes with first-hand experience, both as an officer in the attorney-general’s department in Canberra and as legal counsellor in the Australian embassy in Jakarta.

McKenzie sets out to analyse the extensive cooperation on criminal justice between the two countries, and to make suggestions about strategies for future cooperation. The result is engrossing. He supports his argument with reference to more than one hundred interviews he conducted with Australians and Indonesians involved in areas such as counterterrorism, extradition and people smuggling. The interviews show that what was a modest level of bilateral police cooperation prior to the 2002 Bali bombings has become a relationship of mutual trust and respect. When in Jakarta, I observed the way this relationship worked in the counterterrorism sphere, where the AFP provided intelligence to the Indonesian national police, who acted on it, and rightly gained public acclaim for their successful operations.

The book is at its best in illustrating the ways in which Indonesian and Australian police personnel have interacted with one another over the past twenty years. The interviews evoke the sense of collegiality that has been fostered both by the common objective of preventing crime and by a shared language of law enforcement.

McKenzie argues convincingly that an essential element in the Australia–Indonesia relationship is a perception that the cooperation benefits both countries. This has persisted through periods of tension, such as the acrimony that followed the 2013 allegations of Australian bugging operations targeting Indonesian president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, his wife and senior officials. The value of the relationship has only been questioned when that sense of mutual benefit becomes strained. McKenzie gives as an example a period when Indonesia believed that Australia was not sufficiently expediting extradition requests, despite explanations from Australia about the delays inherent in its legal system. This thesis rings true to me, and reminds me of the way the AFP, proven deliverers for Indonesia in the counterterrorism sphere, secured a high level of engagement from the Indonesian police in anti-people-smuggling work, which was not an Indonesian priority.

To McKenzie, the bilateral relationship has two core dimensions: governmental, involving pursuing political interests, and bureaucratic, involving officials and organisations pursuing policy interests. He argues that there is a tension between these political and policy interests, which results from the differences between the various key players, including private actors such as the media. But he draws perhaps too sharp a line between the interests and actions of what he terms the political and the policy players. His argument is, essentially, that “national politicians are forever playing to their domestic constituencies” and “political parochialism and policy ambition pull against each other”.

McKenzie is undoubtedly correct that from time to time political differences have dogged the pursuit of enduring interests. A scorecard might well include difficulties caused by Indonesia, particularly in its pre-democratic phase, such as hostilit...

Índice

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Editor’s Note

- Hugh White: In Denial

- Jenny Hayward-Jones: Cross Purposes

- Katerina Teaiwa: No Distant Future

- Sean Dorney: The Papua New Guinea Awakening

- The Fix

- Reviews

- Correspondence

- The Back Page by Richard Cooke

- Back Cover

Estilos de citas para AFA6 Our Sphere of Influence

APA 6 Citation

Pearlman, J. (2019). AFA6 Our Sphere of Influence ([edition unavailable]). Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/866770/afa6-our-sphere-of-influence-australian-foreign-affairs-issue-6-pdf (Original work published 2019)

Chicago Citation

Pearlman, Jonathan. (2019) 2019. AFA6 Our Sphere of Influence. [Edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. https://www.perlego.com/book/866770/afa6-our-sphere-of-influence-australian-foreign-affairs-issue-6-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Pearlman, J. (2019) AFA6 Our Sphere of Influence. [edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/866770/afa6-our-sphere-of-influence-australian-foreign-affairs-issue-6-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Pearlman, Jonathan. AFA6 Our Sphere of Influence. [edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd, 2019. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.