![]()

CHAPTER 1

HORSES, TWINS AND GODS

Introduction

The Capitol of Rome is dominated by the famous equestrian statue of the emperor Marcus Aurelius. There was originally a defeated enemy under the raised leg of his horse, but even without this prostrate victim, nobody needs to tell us that Marcus Aurelius must have been a very powerful and important man.1 We understand the statue's message almost instinctively, because this message has been delivered to us so often. In ancient Athens, a horseman (hippeus) was an aristocrat;2 in ancient Rome the Equestrians were just below the Senatorial aristocracy.3 Even today, the capital cities of the world are filled with kings and generals on horseback, who do their very best to imitate the imperious gaze of Marcus Aurelius: Henry IV commanding the Seine, a brittle Charles I bewildered by the traffic around him, a very aristocratic George Washington overlooking the undemocratic grandeur of Commonwealth Avenue. These powerful men stare over our heads – we are literally beneath their notice. And this is how we expect things to be. For 3,000 years, the horseman has been a powerful image of the aristocratic gentleman. In German, a gentleman is a ‘rider’ (Ritter); in the Romance languages, he is a ‘horseman’ (caballero, cavaliere, chevalier). To this day, English-speakers describe well-mannered men as ‘horsemanlike’ (chivalrous), and Germans describe them as ‘riderlike’ (ritterlich). So we expect horsemen to be better than us and to rule over us. The ancient Roman statue of Marcus Aurelius is an early example of this image of the ruling horseman, and the countless imitations it has inspired still speak to us.4

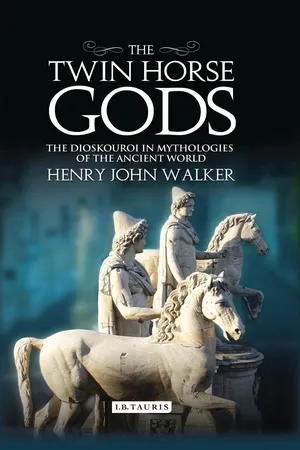

There is, however, a very different image of horsemen on the same Capitol in Rome. At the very edge of the terrace, overlooking the city of Rome, standing in front of the emperor, are two statues of young men with horses. Most of us tend to ignore them because, even if they loom over us as we climb up the Capitol, they disappear from our field of vision as soon as we reach the top. Michelangelo has ensured that our gaze is instantly drawn to the statue of the emperor by the very design of the Capitol itself. We also dismiss these two sculptures because even though they show men with horses, they are not equestrian statues. These young men are not riding their horses; they are leading them by the reins. We could almost mistake them for servants of the emperor, holding fresh horses for him in case he should decide to change his mount. These young men are, however, vastly superior to the emperor himself. They are the ancient Roman Dioscuri, the young sons of Jupiter himself, the twin horse gods, Castor and Pollux.

The contrast between the equestrian statue of the emperor and the sculptures of the horse gods reveals an ambiguity in our attitude to horses. We are brought up to admire them as symbols of aristocratic power, but we also know that they are farm-animals and require a lot of care. A statue of a ‘great leader’ on horseback might be considered a fine and noble thing, but not too many people would like to work as a stable-boy. We readily understand why cleaning out the stables of Augeias was regarded as one of the impossibly difficult Labours of Hēraklēs.5 It is surprising, therefore, to find that the horse gods are ready to perform such a lowly task as looking after their own horses. This surprise is reinforced by the stories told about the horse gods.

There is a nice anecdote from ancient Rome that brings out the contrast between the aristocratic world of the horse rider and the humble world of the horse gods. An ordinary Plebeian called Publius Vatinius was going to Rome, when the horse gods rode up to him and told him that the Romans had won a great victory overseas. Vatinius rushed into the Senate to report the good news, but ‘he was thrown into jail for insulting the majesty and dignity of the Senate with such a silly story’. Later, of course, the Senate had to apologize for its mistake.6 This story draws a powerful contrast between the aristocratic arrogance of the senators, who were outraged that this humble citizen would dare to intrude on their meeting, and the friendly behaviour of the horse gods, who thought it perfectly natural that they should deliver their very important message to a very ordinary Roman.

If we are to understand the horse gods, we must lay aside the 3,000-year-old notion that horse riding is for kings. Instead, we must adopt the attitude of the Bronze Age and see it as a very lowly activity, suitable only for cowboys and messengers.7 This attitude survived into the historical period of the Greek world, where the Dioskouroi are modest and helpful gods, and are very close to ordinary people. In the Bronze and Early Iron Ages of Vedic India, where they are called the Aśvins, we find that the young horse gods have similar characteristics. They are quick to come to the rescue whenever anyone is in trouble, and they are especially ready to help the old, the weak, the humble. For thousands of years the character of the horse gods remains the same. They distance themselves from the high and mighty, and instead they behave like very helpful messenger boys, who are only too eager to come to the assistance of anyone they may meet, as they wander around the world.8 They are the gods of working people; in fact, they are so close to ordinary people that doubts are raised about their status as gods in the myths of India and Greece. They are almost too human.

Twins

Why are the horse gods like this? Why are they so helpful to people? Oddly enough, the answer that has often been given to this question is that they are twins. The Indians always referred to them as ‘the two horse gods’ (aśvinau), using the dual form of the noun to emphasize that they were a pair. The Greek story of their birth made it clear that the Dioskouroi were twins. The Romans explicitly referred to the horse gods as ‘the Twins’ (Gemini), and they are still honoured by that name in the night sky. According to many scholars who have written about the horse gods, the mere fact that they are twins explains everything about them.9 These scholars believe that there are certain universal features shared by all twins in the mythical and religious views of every culture, so the character and careers of our horse gods are quite predictable from the very fact that they are twins. In effect, they believe that all human beings have reacted to twins in the same way, that this universal fear of twins is ‘the oldest religion in the world’.10 Their grand theory about twins is known as ‘Dioscurism’.

The most striking thing about Dioscurism is not its content, which consists of extraordinary and implausible generalizations, but rather its general acceptance by the scholarly world. The theory of Dioscurism was developed at the beginning of the twentieth century by the biblical scholar Rendel Harris. His theory was accepted by anthropologists,11 he is quoted with respect by scholars who write on the subject of the horse gods,12 and his work is still cited with approval in the 2005 edition of the Encylopedia of Religions.13 Harris started off by studying Christian legends about twins, and he was particularly fascinated by the Syrian Acts of Thomas, which stated that St Thomas and Christ were twin brothers.14 They possess what Harris believed to be the essential features of ‘Dioscuric’ twins: they both have the same mother, but one twin is human and the son of a man, whereas the other is divine and the son of a god. Harris rejected this legend as a pagan survival, as an attempt to assimilate Christ and St Thomas with the Dioskouroi.15 Given the popularity of the Dioskouroi, this was a plausible explanation, but then Harris went on to explore the origin of the divine twins themselves, and in two vast anthropological studies16 he concluded that they had developed from taboos surrounding real human twins. According to Harris, this fear and worship of human twins was the original religion of the world, and it was the origin of most religious beliefs except his own.17 He called this religion ‘Dioscurism’, and in this he was followed by his student Krappe, who significantly titled his synopsis of Harris's theories, Mythologie Universelle.18 Harris ultimately concluded that this great universal rival to Christianity was itself based on a primitive Trinity, which consisted of the Thunder-God and his two ‘Assessors’,19 the divine twins.20

Harris firmly believed that every tradition relating to twins could be attributed to this worldwide religion of Dioscurism, as is clear from the conclusion to his Cult of the Heavenly Twins:

We have now taken our rapid survey of what may, perhaps, be described as the oldest religion in the world; a religion which is still extant in some of its simplest and most primitive forms, though, of course, it will very soon disappear.21

His work also betrays a strong sense of indignation against the practitioners of Dioscurism. Since twin infanticide was practised in some parts of Africa, his crusading zeal against this imaginary religion is understandable, but his tone is invariably mocking and offensive, even when there is no question of infanticide. His followers may not share his indignation or his belief in a single, worldwide Dioscuric religion, but they do accept the idea that there are certain universal practices and attitudes toward twins. In effect, they deny the existence of the ‘oldest religion in the world’ but accept the universality of its beliefs. This is the tragic flaw of Dioscurism, because what Harris and his followers are in fact describing is not a single, universal set of beliefs, but rather an extremely diverse variety of beliefs and practices relating to twins.

Given this variety, it is of course very easy to come up with coincidences between individual practices and beliefs found in one or more societies throughout the world, but these coincidences do not constitute a universal, underlying pattern. Modern anthropologists who study twins have rightly drawn attention to the extraordinary diversity of African beliefs, even ‘among peoples who live side by side’.22 Some scholars have suggested that twin infanticide is not a separate phenomenon from infanticide in general,23 but the harsh reality is that infant twins (just like infant girls) are regularly put to death or left to die because their desperately impoverished mothers cannot afford to raise them and because they are considered to be a manifestation of supernatural evil.24 There is no such thing as Dioscurism or a single universal approach towards twins; there are hundreds of diverse attitudes, each one peculiar to its own society.

The followers of Harris organized his meandering works into a system. The ethnologist Sternberg in 1916, the folklorist Krappe in 1930, and another folklorist, Ward, in 1968, formulated the general principles of Dioscurism:25

(a)Dual paternity: twins are born when a human mother sleeps with a god and with a man.

(b)Twin tabu: the mother and her twins are banished from society, if not murdered.

(c)Magic powers: twins have superhuman powers, but their divine status is dubious; they use their powers to benefit the human race, they rescue people and promote fertility.

It would be absurd to claim that any of these three beliefs is accepted throughout the world, but it might be worthwhile asking whether they are found in India and Greece. They would, after all, provide us with one way of explaining wh...