eBook - ePub

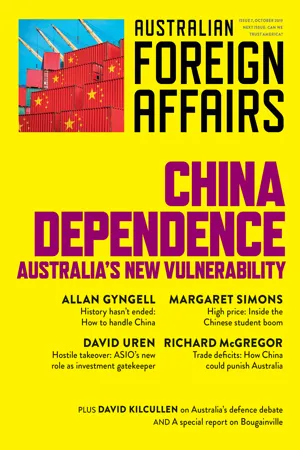

AFA7 China Dependence

Australian Foreign Affairs; Issue 7

Jonathan Pearlman, Jonathan Pearlman

This is a test

- 96 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

AFA7 China Dependence

Australian Foreign Affairs; Issue 7

Jonathan Pearlman, Jonathan Pearlman

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

"There is no Australian future – sunlit or shadowed – in which China will not be central." ALLAN GYNGELL The seventh issue of Australian Foreign Affairs explores Australia's status as the most China-dependent country in the developed world, and the potential risks this poses to its future prosperity and security. China Dependence examines how Australia should respond to the emerging economic and diplomatic challenges as its trade – for the first time – is heavily reliant on a country that is not a close ally or partner.

- Allan Gyngell calls on Australia to dial back its hysteria as it navigates ties with China.

- Margaret Simons explores whether Australia's universities are banking unsustainably on Chinese students.

- Richard McGregor considers Australia's trade dependence on China and the dangers of economic coercion.

- David Uren probes ASIO's expanding role in monitoring foreign investment and asks if Australia's fears are trumping opportunities.

- Ben Bohane reports from Bougainville in the lead-up to its historic referendum on independence.

- Melissa Conley Tyler proposes a new funding model to reinvigorate the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

- David Kilcullen offers a US perspective on Australia's defence vulnerabilities and capabilities.

PLUS Correspondence on AFA6: Our Sphere of Influence from Jonathan Pryke, Wesley Morgan, Sandra Tarte and more.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es AFA7 China Dependence un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a AFA7 China Dependence de Jonathan Pearlman, Jonathan Pearlman en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Politics & International Relations y Geopolitics. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

Politics & International RelationsCategoría

GeopoliticsHIGH PRICE

Inside the Chinese student boom

Margaret Simons

International education is one of Australia’s largest export industries, coming in behind coal, iron ore and now the natural gas industry. But there is a dissonance here – a contradiction.

There is surely a difference between digging, extracting and shipping out the earth’s resources, and bringing in hundreds of thousands of young people, all in search of self-improvement, a leg up in the job market back home, a better life in Australia, or all three. Mining exports are relatively simple. Young people are complicated.

The education of international students, including their tuition fees and the money they spend on accommodation, food and other living expenses, brings in an estimated A$35.2 billion, or 8 per cent of total exports. It’s a massive business.

Chinese students represent about one-third of the students who come to Australia, but a larger proportion of the dollars – because they gravitate to the prestige of Australia’s top universities, where the fees are higher. They have already transformed the campuses and our cities. Step into a lift at any leading Australian university and you are as likely to hear Mandarin spoken as English. Visit the café strips nearby and drink bubble tea, a sweet tapioca-bead drink. It was almost unheard of in Australia fifteen years ago; now it is everywhere. So are cheap and good noodles. International students are also one of the main drivers of the high-rise micro apartment trend in our inner cities.

Such changes, though, are superficial. They could be reversed quickly. Underlying them are bigger shifts in the way this country works. Chief among these is the interaction between immigration policy and education. We are selling not only degrees and qualifications, but also access to the Australian labour market and insights into our way of life. The boom in international students is part of a fundamental change in Australian immigration – from an entirely controlled, capped system of permanent migration to an intake that includes a largely uncapped intake of temporary migrants. These temporary migrants include backpackers and overseas workers, but students make up a large cohort and are driving the increase. They are likely to stay longer – a significant proportion gain permanent residency.

So, almost without public controversy, or even public awareness, universities rather than the federal government are determining, to quote former prime minister John Howard, a large proportion of “who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come”.

The students are not the same as truckloads of ore. They are of course changed by their Australian education, as we would hope. But perhaps they are not changed as much as they change us.

The rankings cycle

Chinese students have altered the dynamics of our top universities, which are now largely dependent on this single market – particularly to foster the research effort that has propelled them up the world rankings.

International rankings of tertiary institutions – the Times Higher Education list and the Shanghai Jiao Tong list are probably the best known – are increasingly important to universities. They are, rightly or wrongly, taken as markers of success. They are also what draw prestige-conscious students, such as the Chinese. Those rankings are mostly determined by research, as measured by publication in prestigious international journals.

It’s one of the unfailing rules of human institutions that if you introduce a measurement, the system changes to meet it, like the leaves of a plant turning to face the sun. So it is that the research output the international rankings measure grows lush at universities, and those sides of academia not rewarded can dwindle in the shade. One of those things can be teaching. Another is the kind of industry-connected research that can be useful, but doesn’t reach the international journals.

The students lured to our leading universities may never encounter the academics behind the research that attracted the ranking. Instead, they are often taught by sessional staff and those on short-term contracts. According to the National Tertiary Education Union, only one-third of Australian university staff have secure employment, or tenure. Forty-three per cent are casuals – their contracts end at the end of each semester. Twenty-two per cent are on fixed-term contracts, typically between one and two years in length. So, universities have become big employers, but not particularly good employers.

Chinese students make up 60 per cent of all foreign student enrolments

Meanwhile, according to researcher Andrew Norton, who was until recently based at the Grattan Institute, major universities are pumping out more research, leading to rising rankings, leading to more international students, who subsidise more research.

To Norton, the increasing casualisation of the academic work-force is a de-facto risk management strategy. If the boom in international students stopped, universities could downsize much more easily. But the same equation applies: less teaching, less research, a lower position in the rankings.

The money from international students has allowed our universities to do well through a period in which government funding, for both teaching and research, has been cut. It is hardly reasonable to expect them to turn the business away. Yet they are living through a boom. Perhaps the landing will be hard, perhaps it will be soft. What are our best universities doing to manage the risk? What’s the plan for the future? It’s not easy to get satisfactory answers.

China and prestige

The export industry for international education involves five sectors, including school and vocational education and training. Higher education – universities – is by far the largest sector. Chinese students are the largest cohort: 30 per cent of the 595,363 international students currently in Australia. The next largest cohorts are from India, at 15 per cent; Nepal, at 7 per cent; and Vietnam and Malaysia, at 4 per cent each.

As a group, the Chinese often behave differently from students of other nationalities. Most are only children, the legacy of China’s one-child policy. They are the focus of the ambitions and financial resources of both parents and two sets of grandparents. For these families, the prestige bestowed by a top university is important. Meanwhile, students from India and the other developing countries are more likely to be from larger, poorer families. They generally attend vocational colleges and second-tier universities, where the fees are lower, and many hope to use their time in Australia as a stepping-stone to permanent residency and, eventually, citizenship.

The story of Chinese students is mainly about Australia’s top institutions of research and higher learning – the so-called Group of Eight (Go8). They are the Australian National University, Monash University, the University of Melbourne, the University of New South Wales, the University of Queensland, the University of Sydney, the University of Western Australia and the University of Adelaide. Seven are ranked in the top 100 in the world, and all are in the top 150. Since the Chinese student boom began, most of them have risen in those rankings. These universities charge around A$40,000 a year for courses, compared to around A$25,000 a year by the non-Go8 universities.

At the Go8, Chinese students make up 60 per cent of all foreign student enrolments. According to analysis published earlier this year in the Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, the Go8 now earn more from Chinese students than they do from the Commonwealth Grant Scheme, the basic teaching grant that the government pays for the education of domestic students. In 2017, 43 per cent of commencing students at the Australian National University and the University of Sydney were from overseas, as well as 40 per cent of commencing students at Monash. In 2012, it was 23 per cent at the University of Sydney and 24 per cent at Monash. Similar rapid rises have occurred at most Go8 universities.

Australia is the most common destination for students from China after the United States, and the third-largest player in the international student market, after the United States and the United Kingdom. The market in Australia is segmented, with universities tending to be dominated by particular ethnic groups. Andrew Norton notes that this increases the risk for individual institutions. A downturn in the flow of students from Vietnam, for example, would have a significant impact at a university such as Melbourne’s RMIT, but leave others relatively untouched. A downturn in students from China would hit the Go8 very hard indeed.

The Chinese student experience

Time to declare my position in this story. I work at Monash University, one of the Go8, teaching journalism subjects. Before that, I headed the Master of Journalism at another Go8 member, the University of Melbourne. I teach Chinese students. The journalism-focused subjects don’t draw these students in large numbers. Partly, this is because a Western-oriented journalism education is of limited use in China. Partly it is because we demand higher English language skills. But I have also taught into broader media and communications degrees, where it is common for lectures to contain up to 80 per cent Chinese students.

Chinese students have been among my best and worst pupils. The obvious differences – English language capabilities chief among them – obscure the many ways in which they mirror any other cohort. Some students are diligent; others are clearly satisfying parental ambitions rather than pursuing their own. They are often away from parental control and day-to-day support for the first time, with all that implies for fun, personal growth and stress.

In practical journalism assignments, Chinese students naturally gravitate to reporting on their own community. So it is that I have learned, from them, about students who support themselves by smuggling illicit tobacco from China to Australia. I have seen many reports about the Daigou – students and others who buy goods for customers back home concerned about food safety and purity.

My top student last year was Chinese. I will call her Mary, rather than using her real name, for reasons that will become clear. She completed, to high distinction standard, an investigative report on the contract cheating business.

Australian universities are depriving both their international customers and domestic students

Websites that sell essays are marketed to Chinese students in English language countries worldwide. My student interviewed some of those who write the essays. They charge $150 per 1000 words for an assignment designed to attract a pass mark, or more for a credit or a distinction. This is not plagiarism. These are real, original assignments – just not written by the enrolled student. I’d be lying if I said I was confident in spotting them when they cross my desk.

Thanks to Mary’s work, I know that one of the biggest agencies, Meeloun Education, claims to have over 450 writers, more than half with master’s degrees from outside China. They spruik that they can handle assignments in all the major Australian universities, specifically mentioning the University of Sydney, the University of Melbourne, the University of Adelaide and Monash University.

On the strength of this work, Mary got an internship at the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, which has since published its own stories on the contract cheating business. There is now legislation planned to outlaw these websites. Meanwhile, Mary has graduated and secured work helping Australian journalists who are investigating Chinese influence in Australia. She never gets a byline – that would be dangerous – and she doesn’t tell her Chinese friends what she is doing.

I meet Mary in Federation Square, central Melbourne, after asking if she will talk to me for this article. She is thrilled. She tells me she has mentioned our meeting to her mother. Such contact is rare enough to be significant news. This, she says, is the hardest thing for Chinese students. Australians are friendly to them on a superficial basis, but “this notion of personal space, that is very strange and very hard”. Many Chinese students find it hard to penetrate, or even understand, the reserve that surrounds our intimate lives. How can we be so affable, yet back away so fast when a Chinese student responds with an expectation of greater intimacy?

Mary is unusual. Her encounters with Australian journalists mean she absorbs local news and views, and her English is flawless. Yet she still struggles to engage with Australians. Most of her Chinese student friends, meanwhile, move through Australian society in a bubble. They speak English only in class. They consume little Australian media, instead relying heavily on Chinese language social media news services, targeted to Chinese students in Australia.

Associate professor Fran Martin at the University of Melbourne has been conducting a five-year study of Chinese international students. Her subjects are all women – partly due to her research speciality in gender studies, but also because 60 per cent of all Chinese students overseas are female. This imbalance is even more striking given that women comprise fewer than 50 per cent of the Chinese population, thanks to a skewed birth ratio under the one-child policy.

Martin found that the failure to make Australian friends is a major disappointment for Chinese students. Making friends from other countries is one of their main motivations for coming to Australia. They blame their failure on poor English language skills, but Martin sees this as a symptom, not a cause. Australian universities aren’t doing enough to provide them with the experience they seek. The best way to learn a language is to use it – and Chinese students don’t get those opportunities. She tells me, “It’s an indictment on the universities that they don’t do more to break up the cliques, to force interaction.” Teaching staff aren’t trained in the kind of cross-cultural skills needed. They should be doing more to encourage student interaction, she says, and this in turn would help international students improve their English. By failing to do this, Australian universities are depriving both their international customers and the domestic students, who could benefit from such interaction. Despite the numbers of international students, we are not running a genuinely international system of education.

Professor Sue Elliott, deputy vice-chancellor at Monash University, told me that universities are investing in support such as English language assistance and Mandarin-speaking mental health services. How much of the revenue raised by Chinese students is spent on such services? I could not find a single university that releases those figures, though all of those I spoke to nominate the failure to integrate Chinese students as a major risk to the goose that lays those golden eggs.

The experience of being in Australia changes female Chinese students, says Martin, but perhaps not in the ways we might expect. The women return home with a greater sense of independence and are more likely to resist state and family pressure to marry early and have children. But when asked if this is because of their contact with Australian values, they are likely to dismiss the idea. Rather, it was the experience of being away from family that formed them, together with an awareness of the time and money spent on their education.

Australian politics can also be puzzling for Chinese students. Living in the city, they see every demonstration that brings the streets to a halt. Martin says many are intrigued: why are people bothering? When it is explained that enough public attention might change votes, and that might change the government, they understand – but are unlikely to change their view.

This mirrors my experiences in the classroom. In my subjects, Chinese students are often openly critical of their own government, but when China is criticised by others, they can be defensive. Even the journalism students, who crave more media freedom at home, will argue that China’s large population and many challenges necessitate strong party rule. It is rare for a student from China to advocate a Western system of media freedom. And most resent the way in which the Australian media depicts China – and their presence on campus – as a threat.

For Chinese s...

Índice

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Editor’s Note

- Allan Gyngell: History Hasn’t Ended

- Margaret Simons: High Price

- Richard McGregor: Trade Deficits

- David Uren: Hostile Takeover

- Special Report

- The Fix

- Reviews

- Correspondence

- The Back Page by Richard Cooke

- Back Cover

Estilos de citas para AFA7 China Dependence

APA 6 Citation

Pearlman, J. (2019). AFA7 China Dependence ([edition unavailable]). Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/954433/afa7-china-dependence-australian-foreign-affairs-issue-7-pdf (Original work published 2019)

Chicago Citation

Pearlman, Jonathan. (2019) 2019. AFA7 China Dependence. [Edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. https://www.perlego.com/book/954433/afa7-china-dependence-australian-foreign-affairs-issue-7-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Pearlman, J. (2019) AFA7 China Dependence. [edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/954433/afa7-china-dependence-australian-foreign-affairs-issue-7-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Pearlman, Jonathan. AFA7 China Dependence. [edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd, 2019. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.