![]()

PART I

OVERVIEW

Portuguese warfare in Africa revealed the limitations of the European state and its technological approach to warfare. Unlike Europe, Africa had almost limitless land and few easily identifiable strategic targets for the control of its wealth. Military objectives – as European strategists understood them – were hard to identify. Consequently, the rewards of campaigning for European troops were slight and the logistical problems often insuperable. The Afro-Portuguese therefore, not only learned to fight their wars in the only manner possible in Africa, but these wars came to have objectives which were only understandable and therefore achievable in an African context.

With apologies, source unknown

In contrast, Portugal did pretty damn well dominating its African dominions for five centuries. The last time anything like that was achieved was by Rome. Britain’s expansive fiefdoms across the globe lasted only a couple of centuries…

The author

I began my history at the very outbreak of the war, in the belief that it was going to be a great war …

Thucydides

![]()

1

Angola’s War Against the Rebels – The Beginning of the End

Private armies are a far cry from the Sixties dogs of war.

John Keegan, Former Defence Correspondent, Daily Telegraph, London.

Very few military histories start halfway through the campaigns on which they are focussed. This book does exactly that, and for good reason. By capturing Jonas Savimbi’s diamond fields at Cafunfo (near the border with the Congo), a small group of South African mercenaries involved in Angola’s insurgent war effectively severed rebel access to the world outside. Once they had removed diamonds from the battlefield equation almost all UNITA’s external bank balances were effectively ‘frozen’. No sales of precious stones were being generated and that meant no money for weapons…

The great battle of Cafunfo lasted several weeks, though if you include the planning stages and movement of assets needed for such a military adventure, it took months.

The process involved a mechanized strike force that covered hundreds of kilometres in a distant corner of Africa that few of us had heard about, never mind visited. Throughout, the attackers consistently came under fire from an extremely determined adversary, many of whom were not afraid to die for a real or imagined ideal.

These battles – short, sharp and brutal – were fundamental to the kind of conventional onslaughts launched by both sides, the likes of which are rarely taught in such august establishments as West Point, Sandhurst or France’s elite École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr.

At the end of it, the consequences of government forces – sternly backed by a modest group of freelance fighters – taking the diamond fields after the Cafunfo battle were long term. In turn, the rebels had blown it.

Though hostilities would continue for a good while longer, UNITA – a political and guerrilla movement founded, nurtured and commanded by maverick insurgent leader Dr Jonas Savimbi – appeared to lose both the initiative and the momentum linked to the struggle, which had always been a hallmark of this rebel force.

Without the $200 million delivered annually by Cafunfo’s and Catoca’s alluvial diamond diggings, the rebels were deprived of a hefty proportion of the wherewithal they needed to fight their war. In contrast, the Luanda government was coining billions from oil, supplemented by the comparative ‘small change’ it got from diamonds.

In reality, the mechanized assault in Angola’s remote Lunda Norte Province in July 1994 should never have happened. The target lay at the far end of a virtually non-existent road in the middle of nowhere. Throughout, while moving towards its objective, the strike force was exposed in a region that had little cover and almost no prospect for back-up should things go wrong.

Air cover from several Mi-17s operating out of Saurimo – the city lies 300 kilometres to the east of Cafunfo (or roughly three hours flying time there and back) – and almost the entire area in-between was hostile. Should one of the helicopters be forced down, it would have been difficult for help to arrive in time. That did happen, several times in fact, but the saving grace was that South African mercenary aviators always insisted on two-ship operations. If one helicopter went down, the other would land and rescue passengers and crew.

In one such incident, where a Mi-17 Hip was forced down by ground fire, the second helicopter landed and loaded everybody onboard. It was a remarkable achievement: the handbook of the older version of that former Soviet helicopter suggests a maximum load of about 20 troops. By the time everybody had clambered onboard and was ready to head towards Saurimo this time round, the total had upped to 40.

For all that, South African mercenary pilots operating under Angolan Government auspices did what was expected of them and were able to provide several hours of top cover when weather allowed, and sometimes when it did not. It did not help that UNITA had acquired SAMs, and these were used several times against the Hips: mostly Stinger missiles provided some years earlier by the CIA for use against pro-Soviet government forces.

Having given this sophisticated equipment to Savimbi to fight his war against the Marxist Luanda government – quite a few Angolan Air Force jets and helicopters were downed with them – there was no way that Washington could take them back after Soviet influence in Africa had waned.

Still, the missile threat did not deter the South African-backed mercenary force from moving onto Cafunfo and throughout, the Angolan Hips were an invaluable asset. But Angola’s main operational base at Saurimo in the diamond-rich north-east of the country was a long way from the diggings. That meant that quite a few improvisations needed to be implemented, fuel being the main concern.

Since the average Mi-17 has a flying time of about 150 minutes, getting adequate supplies of avgas to intermediate points along the way was a priority, though the mobile column heading towards Cafunfo did provide some fuel, carried onboard trucks in the two-kilometre-long convoy. Additionally, a refuelling point was established at a small town that had been militarily secured on the main east-west road that snaked through the heavily foliaged region some distance south of Cafunfo.

There were many ancillary problems linked to the onslaught. To avoid landmines and ambushes (which took place anyway, two, three and sometimes four times a day) the column had to cut or plough its own route across some of the most difficult bush and jungle terrain on the African continent.

There were several rivers that needed to be crossed, Savimbi having blown the bridges over most of them as soon as he realised in which direction the column was heading. This the South African commanders did with great difficulty even though their column included several Soviet armoured vehicle-launched bridges (AVLBs). Like much else in this improvised strike force, just about everything in the column moving towards the ultimate objective was ‘make-do’.

In the end, having fought the rebels off more times than anybody could recall, the mercenary-led attack group – headed by former Reconnaissance Regiment commander Colonel Hennie Blaauw – managed to reach the diggings, though it took twice as long as they initially expected. Once in Cafunfo and the enemy forced back into the jungle, more Angolan Army troops were airlifted into the area and the combined force set about driving the guerrillas further into the interior.

A difficult process of holding onto their gains followed, which, even with helicopter gunship support, was always tenuous; nobody ever knew if Savimbi had sent for reinforcements and whether another 10,000 guerrillas would suddenly descend on the occupiers. Also, the region was remote from any large or small government post and re-supply was always a problem.

Though the attack force was eventually joined by a second large force of government troops who were brought in overland and who set about consolidating the defences of the Forças Armadas Angolanas (FAA, the successors to FAPLA), the process remained touch-and-go. Ambushes, landmines and booby traps were a constant threat, in large part because the rebel force had originally been trained by the South African Army.

The battle for Cafunfo was to become one of Africa’s classic examples of contemporary insurgency bush warfare.

With Angola’s armour, ground and air assets preparing for battle, Cafunfo almost overnight became the magic word. Nobody had any doubt that the rebels would eventually be dislodged: especially since a new bunch of toughies on the block was involved and Luanda was confident that, as with Soyo, the newly-recruited bunch of mercenaries would do the trick.

Colonel Blaauw knew from the start that the task was daunting. There were innumerable delays, false starts and cancellations, coupled to some Angolan commanders playing mind games in their bids to either enhance their influence or start their own not-so-little diamond-buying cartels. Much of this obfuscation could be sourced to Luanda’s mind-blowing bureaucracy.

At one stage a group of MPLA political commissars arrived at Saurimo. Like a gaggle of Auschwitz oberleutnants, they jackbooted about the base and demanded to know about things that were not only of no concern to them, but had nothing at all to do with the campaign ahead. A quick radio call to Luanda got them all back on their plane.

In Saurimo, during the preparatory stages, there were endless messages, contradictions, debates, not a few heated arguments about who was in charge of what, as well as questions that sometimes made little sense. Forms had to be completed (sometimes in quintuplicate), much of it linked to order groups or staff meetings, though Blaauw and his associates believed that very little of what they wrote or reported in these missives to Luanda were ever read or passed down the line. Additionally, strings of military brass would flip in and out of Luanda and head east towards the diamond fields.

Kafka would have loved the place, especially since most of the senior Angolan commanders had been put through their paces in the Soviet Union. Almost to a man, they tended to do things by the book. The South Africans did not, which was the prime reason these former Special Forces operators were hired to fight Angola’s civil war in the first place: they were totally unconventional in their approach.

That, in essence, was the start of it. Issues were further compounded by delays in the supply of men, equipment and machines, none of which was helped by the fact that Luanda lay on the far side of the country. The distance between the capital and Saurimo – heart of Angola’s diamond industry in the east – is about 1,000 kilometres by road.

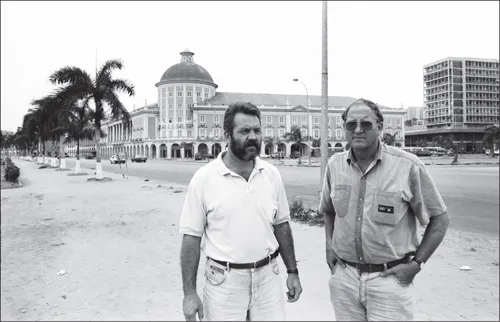

Recruited by the mercenary organisation Executive Outcomes, former Reconnaissance Regiment Colonels Duncan Rykaart (left) and Hennie Blaauw h...