eBook - ePub

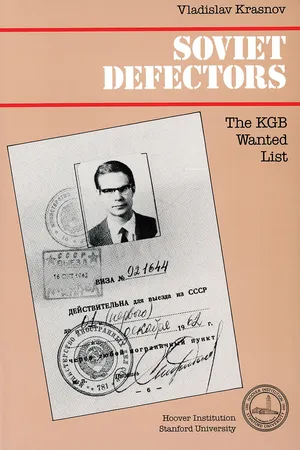

Soviet Defectors

The KGB Wanted List

Vladislav Krasnov

This is a test

- 288 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Soviet Defectors

The KGB Wanted List

Vladislav Krasnov

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

The topic of defection is taboo in the USSR, and the Soviets, are anxious to silence, downplay, or distort every case of defection. Surprisingly, Vladislav Krasnov reports, the free world has often played along with these Soviet efforts by treating defection primarily as a secretive matter best left to bureaucrats. As a result, defectors' human rights have sometimes been violated, and U.S. national security interests have been poorly served.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Soviet Defectors un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Soviet Defectors de Vladislav Krasnov en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Politics & International Relations y Intelligence & Espionage. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

I

SOVIET DEFECTORS IN THE PUBLIC RECORD

1

WHAT HAS BEEN WRITTEN ABOUT SOVIET DEFECTORS?

GORDON BROOK-SHEPHERD’S THE STORM PETRELS

Precious little has been written about Soviet defectors. As far as the defectors of the period prior to World War II are concerned, the first and only book I am aware of was published in 1977 in England. Titled The Storm Petrels: The Flight of the First Soviet Defectors, it was authored by Gordon Brook-Shepherd, a British journalist.1 It relates the stories of five select trailblazers of that long line of Communists who chose freedom: Boris Bazhanov, Stalin’s one-time personal secretary, who crossed the border to Iran on New Year’s Day of 1928; Georges Agabekov (actually Arutyunov), the chief Soviet spy in the Middle East, who led the manhunt for Bazhanov before he himself defected in France in June 1930; Grigory Besedovsky, the acting Soviet ambassador to Paris, who escaped from the embassy in October 1929; Walter Krivitsky, the illegal resident in Holland in charge of Soviet agents in several European countries, who defected in October 1937; and Alexander Orlov, a secret service chief, who had presented Stalin with the entire gold reserves of Spain, 600 tons (still in the USSR), only to run for his life in July 1938.

Although all five had told their stories in their own books, Brook-Shepherd’s volume is more than a simple recapitulation of their memoirs. Drawing, in his words, “from a wide range of Western official sources” and from interviews with some of those storm petrels who were still alive “on both sides of the Atlantic,” most notably Bazhanov, he created his own picture of prewar defection. (Bazhanov died in France in January 1983.)

Brook-Shepherd realizes that these five were not the only defectors of the period and, in fact, he refers to a half-dozen other defectors in his book. Still, his book gives no idea of either the history or the scope of the prewar defections. Moreover, though indexed, his book lacks a bibliography and is poorly footnoted, and therefore is ill-adapted for scholarly use. However, he has turned a sympathetic ear to his defectors, and the book is animated by his awareness of their historical significance and relevance to the present day. “They were not only the political heralds of the Cold War,” writes Brook-Shepherd. “By what they revealed and what they did in exile, this handful of forgotten men helped to shape the course of that great East-West conflict which is still with us.”2

Even though the author himself “devoted hardly any space to drawing morals from these stories,” he concludes his book rather effectively by letting Bazhanov speak for all the storm petrels by quoting from his personal letter:

You know, as I do, that our civilization stands on the edge of an abyss… Those who seek to destroy it put forward an ideal. This ideal [of communism] has been proven false by the experience of the last sixty years… the problem of bringing freedom back to Russia is not insoluble… the youth of Russia no longer believe in the system, despite the fact that they have known nothing else. If the West [develops its] confidence and unity, [it] can win the battle for our civilization and set humanity on the true path to progress, not the twisted path of Marxism.3

This will be so only if the message of the defectors is listened to more attentively than it was before World War II.

COLONEL HINCHLEY’S THE DEFECTORS

Only a little more attention has been paid to postwar defectors. In 1967, Vernon Hinchley, a colonel of British intelligence, published The Defectors.4 Although he does not directly say so, he seems to have an insider’s view on some defections, and he has accumulated a considerable amount of information. Nonetheless, his book is of little use to scholars and not easy reading for anyone because it is poorly organized, makes no reference to sources, and lacks an index.

Above all, the book suffers from lack of understanding of defection as a phenomenon characteristic of totalitarian communist regimes. Hinchley paradoxically defines a defector as someone “who changes sides legally” and who finds his closest kin in a traitor “who changes sides illegally.”5 Treating defection as a “two-way traffic,” East-to-West and West-to-East, Hinchley illustrates his point by citing a few examples of both. In the West-to-East traffic he includes such British agents of the KGB as Guy Burgess, Donald MacLean, and Kim Philby, as well as the nuclear physicist Bruno Pontecorvo, whom he defines as a “nonpolitical” defector “who left Harwell for Moscow for the very sensible reason that he was offered a better job.”6 He also includes in this category three Americans: William H. Martin and Bernon F. Mitchell, both of whom fled to the USSR in 1960, and Sergeant Glen Rohrer, who escaped from Camp King, West Germany, in 1965. The East-to-West traffic he exemplifies with Viktor Kravchenko, Igor Gouzenko, Oksana Kasenkina, Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov, Oleg Lenchevsky, Nikolai Khokhlov, Bogdan Stashinsky (whose name he misspells as Starkinsky), and Aleksandr Kaznacheev.

Hinchley apparently sees no difference between the two groups. It does not occur to him that whereas the West-to-East group chiefly consists of KGB agents who were recruited in the West and escaped to the USSR when their spying activities were about to be exposed, the East-to-West group consists of people who never were pro-Western spies but decided to defect to the West more for reasons of conscience than anything else. Strictly speaking, Hinchley’s use of the term “defectors” for the West-to-East traffic is inappropriate because those Westerners who cannot stand “capitalism,” for whatever reason, do not need to defect at all: they can simply buy a one-way ticket to any Soviet bloc country.

Toward the end of his book, Hinchley expands on his initial definition thus: “The defector is an individual, usually mature, talented and above average in intelligence, who for years has worked honestly and approvingly for his native country” and then happens to “decide that he would be better off, either intellectually or economically” in some other country, and so “he changes sides.” This may be taken as a compliment by some, but I doubt whether any Soviet defector would wish to be interrogated, and have his fate decided, by a professional intelligence officer such as Hinchley. I think a defector would rather entrust his or her fate to any Englishman on the street, who would certainly show more understanding and sympathy.

In fact, Hinchley admits that he has little sympathy for those to whom he devoted his book. Drawing the bottom line under his West-East potpourri of defectors, he puts them down as “mentally tough introverts to whom natural loyalties mean little.” Not believing them capable of being “the life and soul of a cocktail party,” Hinchley concludes: “All I have against the average defector is that I could never like him very much.”7 Of course, he is free to dislike anyone, but he should not have written his book at the level of cocktail party banter. After reading it, one wonders whether, for Hinchley, Russia’s communist revolution took place at all.

JOHN BARRON’S KGB: THE SECRET WORK OF SOVIET SECRET AGENTS

Incomparably more valuable, and more sympathetic toward defectors, is John Barron’s KGB: The Secret Work of Soviet Secret Agents, published in 1974.8 Although it is not a book about defectors per se, it tells more about them than any other book. Conversely, without the information provided by defectors, Barron could not have revealed so much about the secret work of the KGB. Barron readily acknowledged his indebtedness to a number of defectors “without whose trust, courage, and intelligence the work never could have been accomplished.”

Vividly narrated by a seasoned journalist, Barron’s book is good reading for the general public. At the same time, it has all the merits usually associated with scholarly studies: it is thoroughly researched and footnoted; sources and bibliography are listed; and relevant appendixes, an index, charts, and photographs are provided. Moreover, throughout the book Barron usually corroborates the evidence from any particular source with that from other sources, and he convincingly argues his points. I find his book actually superior to many academic products in that he suggests some lessons to be learned. One of them has direct bearing on the present study:

deferential silence about KGB oppressions and depredations must be shattered. Soviet propagandists and apologists have succeeded remarkably in establishing the proposition that to condemn even the most egregious Soviet affront or injustice is somehow to “fan the flames of the cold war.” The reverse is true. Silent acquiescence positively encourages the kind of KGB actions that are the essence of the cold war by suggesting to Soviet rulers that these actions have no deleterious consequences.9

Insofar as the majority of defectors are both victims and prey of the KGB (even though only a small number of them were actually former KGB agents), Barron’s advice was an inspiration for the present study.

THE HARVARD PROJECT

Unfortunately, scholars, including Sovietologists, have paid very little attention to the study of defectors. This was apparently due to the fact that, at least since the establishment of the official USA-USSR exchange of scholars at the end of the 1950s, it has been somehow thought that work about defectors would fan the flames of the cold war. So, whatever scholarly work on defectors was undertaken was done mostly before the onset of peaceful coexistence (later named détente) at the end of the 1950s. Most notable is the Harvard Research Project on the Soviet Social System, which was put together in 1950 and was initially underwritten by the U.S. Air Force.

The admirable idea of the project was to tap a new and abundant source of information about the secretive communist state, namely, the thousands of refugees from the USSR, some of whom were still crowding transit camps in West Germany while others had already resettled in the United States. On the basis of data gathered by this project, a number of books were written by American scholars, including How the Soviet System Works, by Raymond A. Bauer, Alex Inkeles, and Clyde Kluckhohn, and The Soviet Citizen: Daily Life in a Totalitarian Society, by Inkeles and Bauer. The latter, not published until 1959, contains the main body of statistical data from the project. That body of data was collected with the help of a detailed questionnaire, to which there were about three thousand respondents, and 329 “extended life-history interviews.” The main thrust of the questions was to establish a statistical basis for learning about the prevailing attitudes of Soviet citizens to various aspects of Soviet political, cultural, social, ethnic, and economic life.

Although the majority of the respondents belonged to the category of the so-called Displaced Persons (DPs)—that is, those who during the war were either forcibly brought to Germany by the Nazis or fled the USSR of their own free will—there were among them some postwar defectors. As the authors acknowledge, the DP group “was supplemented by an appreciable but generally decreasing flow of persons fleeing from the Soviet occupation forces, from Soviet missions in western countries, and by an occasional person who fled directly from the Soviet Union, crossing through the intervening Iron Curtain territories in the course of his flight.”10

It is not clear how many defectors there were among the three thousand questionnaire respondents. However, among the 329 extended interviews, 91 were conducted “with postwar refugees,” that is, defectors. It is significant that the Harvard Project did not shun the defectors and appreciated their information. That information certainly contributed to the insights into the Soviet system that were gained as a result of the project. In the conclusion to The Soviet Citizen, Alex Inkeles sums up one of those insights:

In the balance hangs the decision as to what the dominant cultural and political forms of human endeavor will be for the remainder of this century and perhaps beyond. It is perhaps only a little thing that separates the Soviet world from the West—freedom. Inside the Soviet Union there are some who ultimately are on our side. But they are a minority, perhaps a small one. Their ranks were first decimated by Stalin and later thinned by the refugee exodus. We had therefore better turn our face elsewhere, rest our hopes on other foundations than on the belief that the Soviet system will mellow and abandon its long range goals of world domination… If we are not equal to the task, we will leave it to the Soviet Union to set a pattern of human existence for the next half-century.11

This was written more than two decades ago. In the years since, in spite of the rise of the dissident and human rights movement in the USSR, Soviet leaders have been successful in setting “the pattern of human existence” for many more millions of people throughout the world, thus proving the West not quite equal to the task of preserving freedom. Among several reasons for this failure of the West, one, not the least important, must be that the West has been putting more trust in the promises of the Soviet leaders than in the warnings of the defectors.12

2

WHAT HAVE DEFECTORS WRITTEN ABOUT THEMSELVES?

Now we shall review a selection of thirteen major books produced by defectors themselves. The first six books—those by Viktor Kravchenko, Igor Gouzenko, Oksana Kasenkina, Grigory Klimov, Grigory Tokaev, and Peter Pirogov—focus on the Stalin era. The next five—written by Peter Deriabin, Nikolai Khokhlov, Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov, Aleksandr Kaznacheev, and Yury Krotkov—shed light on the USSR under Stalin and Khrushchev. The last two books—those by Leonid Vladimirov and Aleksey Myagkov—spotlight the USSR under Brezhnev.

In selecting these authors and books from a larger pool of literature produced by defectors, primary consideration was given to the ones whos...

Índice

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Transliteration

- Introduction

- Part I Soviet Defectors in the Public Record

- Part II The KGB Wanted List: 1945-1969

- Part III Defections from 1969 to the Present

- Conclusion

- Appendixes

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Questionnaire for Defectors

Estilos de citas para Soviet Defectors

APA 6 Citation

Krasnov, V. (2018). Soviet Defectors (1st ed.). Hoover Institution Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/971437/soviet-defectors-the-kgb-wanted-list-pdf (Original work published 2018)

Chicago Citation

Krasnov, Vladislav. (2018) 2018. Soviet Defectors. 1st ed. Hoover Institution Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/971437/soviet-defectors-the-kgb-wanted-list-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Krasnov, V. (2018) Soviet Defectors. 1st edn. Hoover Institution Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/971437/soviet-defectors-the-kgb-wanted-list-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Krasnov, Vladislav. Soviet Defectors. 1st ed. Hoover Institution Press, 2018. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.