eBook - ePub

American Educational History

School, Society, and the Common Good

William H. Jeynes

This is a test

- 496 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

American Educational History

School, Society, and the Common Good

William H. Jeynes

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

American Educational History: School, Society, and the Common Good is an up-to-date, contemporary examination of historical trends that have helped shape schools and education in the United States. Author William H. Jeynes places a strong emphasis on recent history, most notably post-World War II issues such as the role of technology, the standards movement, affirmative action, bilingual education, undocumented immigrants, school choice, and much more!

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que American Educational History est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à American Educational History par William H. Jeynes en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Éducation et Éducation générale. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

CHAPTER 1

The Colonial Experience, 1607–1776

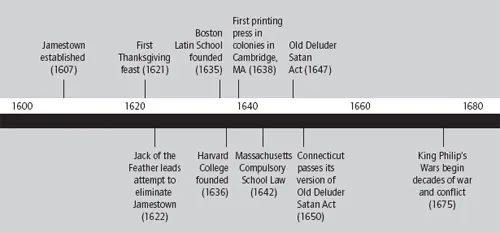

The educational undertaking of the early European settlers who came to the United States was especially important because it established a foundation from which all other Americans built (Bailyn, 1960; Cubberley, 1920, 1934). The contributions that each group made varied, depending largely on the degree of their educational orientation and whether they were able to operate in an atmosphere of peace with the Native American population (Bailyn, 1960; Cubberley, 1920, 1934; Willison, 1945, 1966).

Some of the most salient accomplishments in American educational history were made, in particular, in the first few decades after the arrival of the Pilgrims, in 1620, and the Puritans, in 1630 (Bailyn, 1960; Cubberley, 1920, 1934; Willison, 1945, 1966). Their educational success in establishing Harvard College, the nation’s first secondary school (Boston Latin School), and compulsory education helped launch the nation’s schooling system that would one day become the envy of the world (Jeynes, 2004). Despite these successes, the early settlers also faced challenges in dealing with other cultures, which would spawn a litany of debates that would endure for centuries (Tyack, 1974). Clearly, these debates and successes still live on in American education today.

Although many groups of settlers came to the United States during the 1600s, the Puritans and Pilgrims undoubtedly had the greatest impact on American education (Bailyn, 1960; Cubberley, 1920, 1934). There are two primary reasons for this: First, the Puritans and Pilgrims emphasized education to a considerable degree (Bailyn, 1960; Cubberley, 1920, 1934). Second, for many years, they had a positive relationship with Native Americans that served as a model for other settlers for over half a century (Bailyn, 1960; Cubberley, 1920, 1934; Willison, 1945, 1966). In contrast, many of the other European settlers varied in their academic orientations and the state of their relationships with Native Americans. The importance of an academic emphasis in a community is patent in its impact on the establishment of schools. The state of relations with Native Americans was essential because the presence of peace with one’s neighbors greatly facilitates the starting and operating of schools, especially for the young. In the absence of peace, schools could become easy targets for attack.

In terms of chronology, it is somewhat surprising that the Puritans and Pilgrims had a greater impact on the future of American education than other European groups that preceded them, as well as their contemporaries. However, when one takes a closer look at the Jamestown colonists, who arrived in Virginia in 1607, and the Spanish, who arrived even earlier, in comparison with the Puritans and Pilgrims, one can understand why the latter groups had far greater impact.

THE COLONISTS AT JAMESTOWN

Jamestown was settled by 144 males in April of 1607 (Urban & Wagoner, 2000). The early days at Jamestown were very arduous for the settlers. Within a short time of their arrival, they encountered raids by the Powhatan Native Americans and deleterious diseases, such as malaria and typhoid (Urban & Wagoner, 2000). By the end of 1608, half of the original settlers had died (Johnson, 1997, pp. 24–25). One reason the colony survived despite these calamities was the strong leadership of John Smith. Smith was born in Lincolnshire, England, in 1579. He spent his young adulthood as first a merchant and then a soldier in the Austrian army. Eventually, he was taken prisoner by the Turks and sold as a slave (Stephens, 1872). As a slave, Smith was treated cruelly and later escaped and joined up with the first settlement sent to Jamestown. His difficult experiences taught him how to survive. Consequently, under Smith’s leadership, the emphasis of the Jamestown colony was on survival rather than on education.

The settlers who arrived at Jamestown were sponsored by investors who desired that the settlement be profitable. As a result, the settlers were sometimes greedy, and that was reflected in their treatment of the Native Americans living around them. In the worst episode, Thomas Hunt sailed up the East Coast and captured and enslaved a group of Native Americans. It is also true that the Native American inhabitants in the area around Jamestown were not especially friendly; they were divided regarding whether they should be aggressive or peaceable toward the people of the Jamestown. A Native American whom the settlers called “Jack of the Feather” was one who wanted war with the settlers. He killed a resident, but when a settler’s servant attempted to bring Jack of the Feather to the governor, a struggle resulted and the servant shot him (Eggleston, 1998).

As a result of Jack of the Feather’s death, the local Native American population determined that they would wipe out the population of Jamestown, which had by then grown to 900 or so inhabitants (Eggleston, 1998). They might have succeeded were it not for a Native American boy who lived in a White man’s house and heard of the plot and warned the settlers. As a result, the settlers were able to either flee or defend themselves. Nevertheless, the Native Americans were successful in slaying a large percentage of the Jamestown colonists, killing nearly 350 individuals (Eggleston, 1998). Amongst this kind of hostility, a system of education could not flourish in Jamestown (Marshall & Manuel, 1977).

THE SPANISH COLONISTS IN FLORIDA

The Spanish arrived in what is now Florida in August of 1565, well before the arrival of the English in Jamestown and New England (Milanich & Milbrath, 1989). Initially, 600 Spanish settlers arrived in what became St. Augustine, in the eastern part of the region, on the Atlantic coast. The Spanish colonists arriving there, and later in areas of the Southwest, were looking to profit from the wealth of the area (Blackmar, 1890; Zavala, 1968). The Native Americans throughout Florida, and later other areas that the Spanish settled, did not especially appreciate this emphasis and viewed the Spanish as materialistic and focused on gold (Blackmar, 1890; Zavala, 1968). Primarily because of their focus on profit, the Spanish often mistreated the Native Americans in Florida (Zavala, 1968).

One of the primary reasons that the Spanish did not emphasize education that much is that their goals in colonization were different than those of the English. First, there was generally a much closer connection between the motherland and the “New World” colony in the case of the Spanish than with the English (Landers, 2005; Super, 1988). In the case of the Pilgrims and the Puritans, in particular, these groups fled the religious persecution that they had faced in England (Bailyn, 1960; Cubberley, 1920, 1934). As a result, Spain possessed a more meticulous strategy for their colonies than did the English (Cubberley, 1920; Landers, 2005; Super, 1988). For example, Spain had a detailed plan of how to provide food for their settlements, both via shipping and the self-support of a given colony (Super, 1988). Second, partially because of the close relationship between Spanish colonies and the motherland, the Spanish in Florida and other areas desired to govern the Native Americans under the auspices of the Spanish government (Blackmar, 1890; Landers, 2005; Zavala, 1968). In contrast, the English desired to establish settlements that were distinct and separate from the Native American tribes (Cubberley, 1920, 1934; Landers, 2005). As Landers (2005, p. 28) notes, this attempt at governance caused a series of Native American revolts against Spanish law, and Florida was strung together “by small forts” in order to help enforce Spanish governance. Sporadic attacks by Native Americans continued throughout the 1600s, especially as the Spanish continued to expand their influence throughout much of Florida. This fact caused the Spanish to focus on a military strategy more than an educational one (Blackmar, 1890; Landers, 2005; Zavala, 1968).

Although the Spanish did make incipient attempts to educate both their people and Native Americans by what Landers (2005) calls “rudimentary missions” (p. 28), education was not a primary Spanish focus. However, the Spanish thought that the most exigent problem facing the settlers was to govern successfully and fabricate an affluent economy (Landers, 2005). Therefore, the Spanish settlers concentrated their efforts on the colonists and their Native American subjects, using their skills to produce a healthy economy rather than educate the community (Landers, 2005).

In addition, the Spanish colonists in Florida and the Caribbean lived in a very hostile environment (Marshall & Manuel, 1977). Some Native American tribes practiced cannibalism, and those that did not made the sacrifice of the flesh of the colonists an integral part of their religious rituals (Marshall & Manuel, 1977). Even before the Spanish arrived, numerous Native American groups practiced human sacrifices of their own (Marshall & Manuel, 1977). Surely, a system of education could not exist in the presence of such a threat.

THE PILGRIMS AND PURITANS

The Pilgrims and Puritans arrived in the New World in 1620 and 1630, respectively. Although they were technically two distinct groups, the fact that they both arrived in Massachusetts caused them to eventually function with much the same goals and priorities (Bailyn, 1960). The religious beliefs of the two groups were somewhat different, but they both believed in the need to establish a more pure church. As time passed, the Puritans would far outnumber the Pilgrims, and the two groups tended to increasingly merge in their political and religious beliefs. Given that the similarities of these two groups far outnumbered their differences, many historians treat them accordingly as one societal entity, and that will often be the approach of this author as well.

Puritan Educational Emphasis and Educational Philosophy

Most of the Puritan ministers who first came over to America graduated from Oxford and Cambridge universities (Marshall & Manuel, 1977). At this time, Oxford and Cambridge were considered the finest colleges in England and perhaps in the world (Brooke, Highfield, & Swaan, 1988). Therefore, Puritan leaders were accustomed to the highest educational standards and maintained that the Puritans needed to establish similar standards in New England. They quickly realized the necessity of training ministers born in America to be as educated as possible (Pulliam & Van Patten, 1991). To the Puritans, serving God was of utmost importance, and education was a means to that end.

The Puritans were conservative in their philosophy of education. Cotton Mather and John Cotten were among those Puritan leaders who gave a written detailed description of this philosophy. They believed that both parents and children had certain responsibilities when it came to education (Pulliam & Van Patten, 1991) and promoted what might be called a “holy triad” in education, consisting of the home, the church, and the school.

The Home

The Puritans, as a whole, believed that the home was the central place of education (McClellan & Reese, 1988). They surmised that if the home environment were not right, even if the child attended the best church and the best school, the child would not grow up to be properly educated. The colonists asserted that the home was where the spiritual training given at church and the academic training given at school were applied to everyday living (McClellan & Reese, 1988). The child’s experience at home was therefore to be a type of spiritual, academic, and job-related apprenticeship. To the extent that this was true, the educational training that a child received at home was very child centered.

In colonial days, particularly among the Puritans, the father was much more involved in the raising of the children than we commonly see today (McClellan & Reese, 1988). Part of this paternal involvement resulted from the Christian concept of the Trinity: the Heavenly Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Many colonists believed that children form an image of the Heavenly Father based on their relationships with their own fathers. Therefore, they concluded that the father had a very special role in raising the children. The Puritans inferred a child could gain a sense of the love and holiness of the Heavenly Father only by examining the life of his or her earthly father. This noteworthy role was especially prominent in raising boys. The colonists understood that boys obtain a true concept of what it meant to be a godly man from their fathers. In the eyes of the colonists, therefore, the more time a boy spent with his father, the better off he would be (Eavey, 1964; McClellan & Reese, 1988; Willison, 1966).

When a Puritan boy reached school age, when he was not in school, he often followed his father like a shadow. If the father worked in the fields, the boy worked there with him. If the father owned a shop, the boy often worked with him there as well. Similarly, the girls generally followed their mothers in much the same way. The girls, thereby, learned cooking skills, sewing skills, and the fine points of what it means to be a godly woman (McClellan & Reese, 1988). If the mother ran the village market, her daughter learned how to do this job by her mother’s example.

Most colonial families had what they called “family devotionals,” in which they studied the Bible and prayed together as a family. This family time served the purposes of fostering spiritual growth and family unity, increasing the children’s reading skills, and implanting seeds of spiritual wisdom within the children (Hiner, 1988). During the family time, the Puritans also read the classics of literature and the newspaper together (Hiner, 1988). To the colonists, increasing one’s knowledge was important. Nevertheless, they surmised that unless an individual was grounded in spiritual wisdom, the increased knowledge could be used indiscreetly and could create much harm.

Some people have inaccurate stereotypes of the way Puritans viewed children, believing that Puritans viewed children as “little adults,” though this was actually not the case (Smith, 1973). The Puritans did maintain higher expectations of children than is present in contemporary American society, but this was largely due to necessity (Smith, 1973). The life spans of people were shorter than they are today, and the agriculturally based society meant that work participation depended on one’s physical size more than on one’s age. The larger families of the day also meant that parents needed the help of their older children to care adequately for the young. The Puritans practiced a balance between discipline and encouragement when they raised their children. Cotton Mather (1708) said, “We are not wise for our children, if we do not greatly encourage them.”

The Church

Regarding life as whole, the Puritans regarded the church as the most important member of the triad. However, they believed that the family had more of a salient role than the church in educating children. The church’s purpose in education was to educate the colonists regarding the teachings of the Bible and how to be loving and godly people. People came to church to obtain wisdom. The church was also the educational administration center for the vast majority of educational undertakings and generally operated the elementary and secondary schools, worked together with other churches to develop colleges, and instructed members of their congregations regarding how they should edify their families at home (Hiner, 1988).

Given that the church emphasized knowing the Bible, teaching children to read was considered essential. The Puritans and Pilgrims placed an emphasis on reading the Bible in both American and European schools, where they resided at this time as well.

The School

In Puritan/Pilgrim culture, the school was responsible for fostering the academic development of the child. The Puritans maintained that the most important function of the school was to help produce virtuous individuals. John Clarke, a leading educator, expressed views that were quite representative of New England educators at the time. He believed that a schoolmaster must, “in the first place be a man of virtue. For . . . it be the main end of education to make virtuous men” (Clarke, 1730).

Academically, the greatest emphasis was placed on reading, so that children could read the Bible as soon as possible. The colonial school itself was not child centered. The colonists believed that the children were to listen closely to instruction at school and then apply the lessons at home. The Puritans viewed schools as having a stabilizing influence on society via drawing children closer to God (Pulliam & Van Patten, 1991). In one respect, however, the Puritan/Pilgrim education was more child centered than the schools of the 1800s. With the onset of increased division of labor, industrialization, and urbanization, the role of the home in education decreased considerably over time. As a result, most American homes were less child centered in the 1800s than they were in colonial times (Hiner, 1988; McClellan & Reese, 1988). Men...

Table des matières

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Brief Table of Contents

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 The Colonial Experience, 1607–1776

- 2 The Effects of the Revolutionary War Era on American Education

- 3 Early Political Debates and Their Effect on the American Education System

- 4 Education, African Americans, and Slavery

- 5 The Education of Women, Native Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans

- 6 The Widespread Growth of the Common School and Higher Education

- 7 The Effects of the Events During and Between the Civil War and World War I

- 8 The Liberal Philosophy of Education as Distinguished From Conservatism

- 9 The Great Depression and the Long-Term Effects of World War II and the Cold War on American Education

- 10 The Civil Rights Movement and Federal Involvement in Educational Policy

- 11 The Turbulence of the 1960s

- 12 The Rise of Public Criticism of Education

- 13 The Rise of Multiculturalism and Other Issues

- 14 Educational Reform Under Republicans and Democrats

- 15 Other Recent Educational Issues and Reforms

- Index

- About the Author

Normes de citation pour American Educational History

APA 6 Citation

Jeynes, W. (2007). American Educational History (1st ed.). SAGE Publications. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1004331/american-educational-history-school-society-and-the-common-good-pdf (Original work published 2007)

Chicago Citation

Jeynes, William. (2007) 2007. American Educational History. 1st ed. SAGE Publications. https://www.perlego.com/book/1004331/american-educational-history-school-society-and-the-common-good-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Jeynes, W. (2007) American Educational History. 1st edn. SAGE Publications. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1004331/american-educational-history-school-society-and-the-common-good-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Jeynes, William. American Educational History. 1st ed. SAGE Publications, 2007. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.