eBook - ePub

Textbook of Geriatric Dentistry

Poul Holm-Pedersen, Angus W. G. Walls, Jonathan A. Ship, Poul Holm-Pedersen, Angus W. G. Walls, Jonathan A. Ship

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Textbook of Geriatric Dentistry

Poul Holm-Pedersen, Angus W. G. Walls, Jonathan A. Ship, Poul Holm-Pedersen, Angus W. G. Walls, Jonathan A. Ship

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Textbook of Geriatric Dentistry, Third Edition provides a comprehensive review of the aging process and its relevance to oral health and dentistry. Now in full colour, this third edition has been fully revised and updated with new material encompassing recent research and clinical developments within geriatric dentistry. Written in a clear and accessible style, this is an essential guide to geriatric dental practice for undergraduate and postgraduate dentistry students and practicing clinicians alike.

Key features include:

- Contributions from an international group of expert authors

- Comprehensive coverage of oral healthcare issues in the older adult, from demographics and physiology through to nutrition and pharmacology

- Provides both foundational knowledge and a guide to clinical management

- New chapters including material on orofacial pain, quality of life and treatment planning

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Textbook of Geriatric Dentistry est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Textbook of Geriatric Dentistry par Poul Holm-Pedersen, Angus W. G. Walls, Jonathan A. Ship, Poul Holm-Pedersen, Angus W. G. Walls, Jonathan A. Ship en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Medicina et Odontología. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Chapter 1

Demography – impact of an expanding elderly population

S. Jay Olshansky

School of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

Introduction

Scientists who study the demography of aging investigate trends in, and characteristics of, fertility, mortality and migration and how these components of population change influence, and are influenced by, the environments in which people live. This is a new area of scientific inquiry because aging, as a uniquely demographic phenomenon of populations, has been experienced on a large scale by only one species – humans – and even then only for the last century. Among the many social and economic changes that population aging has brought forth, one of the most important has been dramatic increases in the absolute number of people who live into older regions of the lifespan – a phenomenon that will accelerate in the coming decades.

It is important to understand the difference between population aging and individual aging. Individual aging refers to the biological changes that occur in our cells, tissues and organs with the passage of time, and it is measured demographically at the level of the individual by the duration of our lives. By contrast, population aging is characterized by shifts in the age structure of groups of people such that the relative proportion of older persons (often defined by those aged 65 and older) increases in relation to the number of people under the age of 65. The most common measures that are used to track changes in population aging across time or between population subgroups include the median age, expected remaining years of life (i.e. life expectancy) at middle and older ages and the percentage of the total population aged 65 and older.

Causes and consequences of population aging

For most of recorded history there has been a consistent (stable) pattern of fluctuating birth rates and death rates. Until about the middle of the 19th century, death rates had consistently fluctuated between peaks and troughs as a result of communicable diseases that periodically decimated populations, followed by times of relative stasis. Birth rates were extremely high during most of human history. On average, women gave birth to about seven babies during their reproductive years. Many of the children died in their first year of life from communicable diseases, but death rates were also extremely high throughout the age structure. In fact, the risk of death was so high at middle and younger ages that survival into older ages (beyond age 65) was a rare event by comparison to survival patterns observed today. Living into extreme old ages (ages 85 and older) was an extremely rare occurrence. Since birth rates have almost always exceeded death rates by a small margin throughout most of our history, the size of the human population has grown steadily for thousands of years.

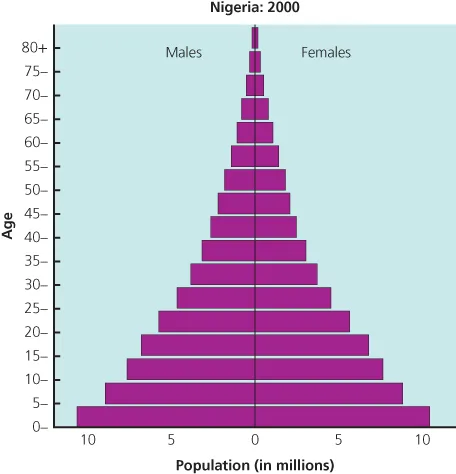

If you were to count the number of people alive at all ages in a given year and plot them on a graph, what you would see is a characteristic age distribution that resembles the shape of a pyramid (see Figure 1.1). This is a common age pattern among humans and many other forms of life where there are a large number of young followed by progressively fewer middle aged and older members of the population. In a hypothetically closed population with no migration, the horizontal bars in the age pyramid reflect the number of people surviving to each age range from an original birth cohort based on prevailing death rates. However, in an open population with migration and changing vital rates (which reflect the true nature of living conditions), the age pyramid reflects historical patterns of fertility, mortality and migration. The age pyramid is what characterized the human age distribution throughout most of our history, but this changed rapidly during the 20th century.

Figure 1.1 Age pyramid for humans in Nigeria in the year 2000.

Source: United Nations, 2001.

During the last 100 years a combination of events led to dramatic changes in the stable patterns of birth rates and death rates that had likely existed for thousands of years. Advances in public health led to the availability of clean water and refrigeration, sewage disposal and improved living and working environments. These developments combined with modern medicine to significantly reduce the transmission of, and death rate from, air- and water-borne infectious diseases. Within a single generation the environmental conditions that permitted the easy transmission of diseases that killed infants and children and women during childbirth were profoundly altered. From a biological perspective, modifications of this magnitude and importance suggest that fundamental changes in the forces of natural selection operating on the human species had occurred.

As the risk of death at younger ages declined rapidly, the high birth rates that were needed to replace the children who died from infectious diseases began to subside. Since the decline in birth rates lagged behind the decline in death rates, the result was rapid population growth during the 20th century – from one billion in 1900 to more than 6.5 billion by the turn of the 21st century. The eventual transformation of birth rates and death rates to the lower levels now observed in most developed nations is what set the stage for the demographic phenomenon of population aging.

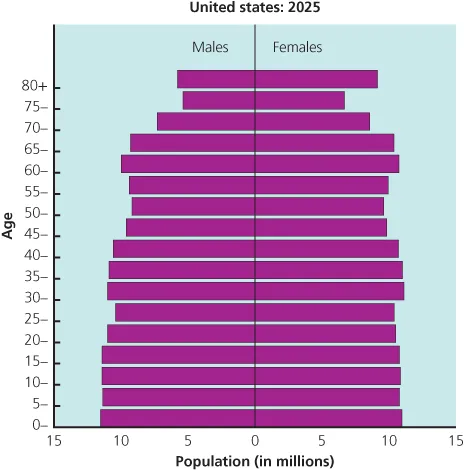

When death rates declined at younger ages, the base of the age pyramid expanded and its apex became smaller by comparison. When the apex of an age pyramid decreases relative to its base, it may be said that a population is becoming younger. Thus, the first demographic consequence of declining early-age mortality was a younger population. However, within a single generation those saved from dying at younger ages began to reach middle and older ages, thereby altering the population's age composition by increasing the size of the middle and apex of the age pyramid relative to its base (see Figure 1.2). When death rates at younger ages stabilize at extremely low levels, as they have in all countries with high life expectancies, the base of the age pyramid then becomes sensitive only to changes in birth rates. With a stable base and a growing middle and apex, a permanent shift in the age structure occurrs from its historical pyramid shape to that of a square-like or rectilinear form. Although temporary increases in birth rates (like those observed in the post-World War II era) can slow population aging and even temporarily reverse it, the new rectilinear age structure will eventually reassert itself as the children from the larger birth cohorts survive to older ages. The transformation from stable high birth and death rates to stable low birth and death rates has led to permanent changes in the age structure of the human species.

Figure 1.2 Age pyramid of the future with a shift in the historical pyramidal shape to that of a square-like or rectilinear form.

Source: United Nations, 2001.

The social, economic and health implications associated with population aging are profound. Consider an ongoing debate in the health and demographic sciences known as the compression versus expansion of morbidity hypotheses. When death rates decline at younger ages the proportion of each birth cohort surviving past ages 65 and 85 increases rapidly. By way of example, in France the proportion of the female birth cohort of 1900 that was expected to survive to ages 65 and 85 based on death rates in that year was 39% and 3.5%, respectively. By comparison, the female birth cohort of 2000 is expected to have 90% and 50% survive past ages 65 and 85, respectively. These unprecedented patterns of survival into older ages are now common throughout the nations of the developed world, and they have led scientists to track the health of these aging pioneers and how prospective changes in death rates at older ages might influence the future health of the older population.

One school of thought argues for what has come to be known as the compression of morbidity hypothesis. With this hypothesis it is suggested that lifestyle changes and advances in medicine will continue to reduce the risk of death from fatal diseases and simultaneously lead to a postponement in the onset and age progression of the nonfatal disabling diseases. The premise of this theory is that there is a fixed biological limit to life towards which populations are headed, and as improved lifestyles successfully postpone the onset and expression of fatal diseases and nonfatal but highly disabling diseases and disorders, more people will be pushed towards their biological ‘limit’ to life, and morbidity and disability will be compressed into a shorter duration of time before death.

A second school of thought proposes what has come to be known as the expansion of morbidity hypothesis. The proponents of this hypothesis maintain that the forces influencing the onset and age progression of nonfatal diseases associated with senescence are mostly independent of the forces influencing the risk of death from fatal diseases. If death rates from fatal diseases continue to decline, it is hypothesized that the saved population will be exposed to a longer duration of time during which the nonfatal but highly disabling diseases and disorders of senescence have the opportunity to be expressed. In other words, the extension of life resulting from continued progress made against fatal diseases is hypothesized to eventually prolong the period of disability in old age among future cohorts of older persons.

A debate has taken place in the scientific literature regarding these two important hypotheses. Although the evidence suggests that in the 1980s several countries were experiencing an expansion of morbidity, since then there is evidence to suggest that some compression has been occurring. However, research in this area should be interpreted with caution because empirical studies addressed to this debate have focused on health transitions observed only during the recent ...