![]()

Part I

Rethinking the garden

![]()

1 Hygiene, education and art

Roberto Burle Marx’s 1930s modern gardens in Brazil

Aline de Figueirôa Silva

Introduction

The Brazilian artist Roberto Burle Marx (1909–1994) is considered to be one of the leading landscapers of the twentieth century. His vast work ranges from squares to large-scale parks, public and private gardens, paintings, tapestries, crystals, jewels and other artefacts. During a period of intense cultural debate, renewal of the arts and construction of Brazil’s national identity, Burle Marx conceived, based on principles of painting, botany and ecology, his concept of the modern garden by using native vegetation as a means for enhancing Brazilian roots.

His main principles were already in place when he designed his first public gardens (Recife in the 1930s), which according to Burle Marx himself “was fundamental to the course that my professional activity took on” (Marx 1985, 70). In addition, and in what concerns the use of native plants, one of his main sources of inspiration was the work of Auguste François Marie Glaziou, the French landscaper at the service of the Portuguese Royal Court in Brazil, author of the main nineteenth-century gardens in Rio de Janeiro, and “precursor of the botanical travels that explored the inland of Brazil” (Sá Carneiro 2017, 82).

Roberto Burle Marx was born in São Paulo in 1909. He was the son of Cecília Burle, a member of a traditional family of French ancestry, and Wilhelm Marx, a German Jew from Stuttgart. The family moved to Rio de Janeiro in 1913. Even as a child, he nurtured an uncommon interest in plants and came to develop his taste of botany by observing the species in the garden of his parents’ home and by reading the German journal Gartenschönheit, brought from Europe by his father, and which allowed him to get in touch with parks and gardens in other countries, as well as with Brazilian plants that revealed to him “a world hardly known” (Marx 1985, 71).

In 1928, Burle Marx travelled to Germany for medical treatment for eye problems. In Europe, he went to concerts, visited exhibitions, and attended music and painting classes. In Berlin, he visited the greenhouses of the Botanical Garden of Dahlem, where he first became acquainted with the Brazilian native flora, gazing at its incredible potential. It was then, “before a greenhouse of Brazilian tropical plants”, that he took “the decision to build, with the native flora, a whole new order of plastic composition, for drawing, for painting, and even reaching the landscape and the garden” (Marx 1954, 18). Upon returning to Brazil in 1930, he attended a course on painting at the Escola Nacional de Belas Artes (National School of Fine Arts) in Rio, directed by the architect Lucio Costa. Two years later, he designed his first garden for a private residence – the Schwartz house – by the architects Lucio Costa and Gregori Warchavchik.

However, it was in the city of Recife, the capital of the northeastern Brazilian state of Pernambuco, that he designed and created his first public gardens.1 Appointed as Head of the Department of Parks and Gardens of the Architecture and Building Department (DAC) of the Government of Pernambuco upon Lucio Costa’s suggestion, Burle Marx was in charge of designing and remodelling several public gardens in Recife. In total, between 1935 and 1990, he submitted 58 projects in Pernambuco, at least 21 of which – 17 public and 4 private gardens – dated from the period between 1935 and 1937 (Sá Carneiro, Silva and Silva 2013, 243–245).2 Out of the 17 public gardens, 8 were in fact built or remodelled, 3 never came to life, and it is unclear what happened to the remaining 6 (Sá Carneiro, Silva and Silva 2013, 243–245). Burle Marx’s plan for public gardens in Pernambuco included 15 squares, a zoological and botanical garden, and a public park. These new public gardens – both new projects in suburban neighbourhoods and remodelled pre-existing gardens located in the historic centre of the city – used open spaces already laid out in the urban fabric.

During his time in Pernambuco, Burle Marx grew close to other young artists and intellectuals such as the architect Luiz Nunes, the engineers Antônio Bezerra Baltar, Attilio Corrêa Lima, Ayrton de Carvalho and Joaquim Cardozo (also a poet), the writer Clarival do Prado Valladares, and the sociologist Gilberto Freyre. In Recife, he wrote articles, gave interviews, attended parties and got in touch with local traditions. The landscape of Recife and the profile and functions of gardens in human history as a sign of human agency were the main topics of his articles. In “Jardins para o Recife” (“Gardens for Recife”), published in the Boletim de Engenharia (Engineering Bulletin) in March 1935, the landscaper stated:3

A garden is in its essence organized nature, subordinated to architectural laws. […] Gardens across all times and among all peoples, emerged at the omega of their respective civilizations. […] All relevant cities have gardens. Thus, one may conclude that gardens are rather a conscious necessity than simply an accidental creation of superfluous luxury in our civilization. In every garden there is always a plan for ordering nature. What changes across time is just its spirit. […] The modern garden does not escape this logic. This is why it encompasses several objectives: hygiene, education and art.

(Marx 1935a, n.p.)

As such, Burle Marx envisaged gardens as architectural creations, emphasizing the historical dimension of their uses and stressing that modern gardens were part of this long tradition by fulfilling specific functions related to hygiene, education and art.

Hygiene, education and art: Roberto Burle Marx’s modern garden foundations

By anchoring his understanding of the modern garden on the trio hygiene-education-art, Burle Marx emphasized vegetation as one of its main protagonists. Plants were the main actors both for conveying the artistic and cultural messages underlying the landscape arrangement and for structuring outdoor urban leisure spaces in a tropical country such as Brazil, and particularly in a hot and humid city such as Recife.

Hygiene-wise, the modern garden stood for “a true collective lung” for the working class, as well as for the less well-off children. It was a space where “the urban inhabitant came to breathe a little fresh air, tired of the daily struggle in small offices, paved streets and factory environments”, and where “children living in perched apartments, small yard houses or collective dwellings” could enjoy their toys and breathe “an air free of contamination”. To achieve these goals “in tropical climates” it was “indispensable” to introduce into gardens “trees able to cast huge shadows” (Marx 1935a, n.p.). From an educational point of view gardens were tools for botanical instruction, as well as spaces for nourishing a balanced relationship between city dwellers and nature. In Burle Marx’s words, they should awake in the “inhabitant of the city a little love for nature and provide him with the means to distinguish local plants from exotic flora” (Marx 1935a, n.p.). Finally, concerning art, the modern garden “should comply with a basic idea and all parts should be subordinated to a coherent ensemble […]. This harmony of the whole garden is deemed vital to human well-being” (Marx 1935a, n.p.).

Burle Marx reasserted these three principles in his 1935 article “Jardins e Parques do Recife” (“Gardens and Parks of Recife”), published in the newspaper Diario da Tarde, stating that an “integral part” of the city gardens “should fulfill a function, or to be more precise, many functions: hygienic, educational and artistic. When a garden achieves these goals, it showcases the level of culture of a people” (Marx 1935b, 1). In interpreting these three propositions, Sá Carneiro (2017, 84) synthesized Burle Marx’s gardens as “a human intervention in nature, which manipulates the existing living elements, such as vegetation, water, and soil, as well as the few built elements”.

Bearing in mind the trio hygiene, education and art, two premises underlie the role of plants as main actors in Burle Marx’s modern garden. The first refers to plants as part of a whole; that is, their mutual relationships and the principles that rule their selection and organization in situ. The second concerns plants and their relationships with human beings; that is, the way users appropriate the garden.

According to the first premise, gardens should obey the laws of composition of architecture and painting – relationships of symmetry, contrasts between light and shadow, interaction among the different volumes of trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants, textures formed by canopies, trunks, foliage and flowers – and of botany and ecology – the observation of plants in their natural habitats, associations of species, compatibility between vegetation and environment, and its adaptation conditions. According to the second premise, gardens should respond to the recreational needs of urban populations and to reduce heat in tropical cities. Burle Marx conceived of gardens as privileged public spaces where city dwellers could find shelter and fresh spots to escape the hot tropical climate and, at the same time, become knowledgeable about the native flora of several Brazilian regions and, in particular, of the region where they lived.

Local landscapes and their physical, biotic and anthropic attributes (rivers, soil, relief, climate, fauna and flora, adjacent buildings, customs and cultural practices, etc.) are at the core of both premises: vegetation as an essential attribute both for the composition of gardens and their uses. These ideas were already present in the first two gardens designed in Recife in 1935: the Praça de Casa Forte (Casa Forte Square) and the Praça Euclides da Cunha (Euclides da Cunha Square).

New garden projects: the enhancement of the indigenous flora of Brazil

A Praça de Casa Forte (Casa Forte Square)

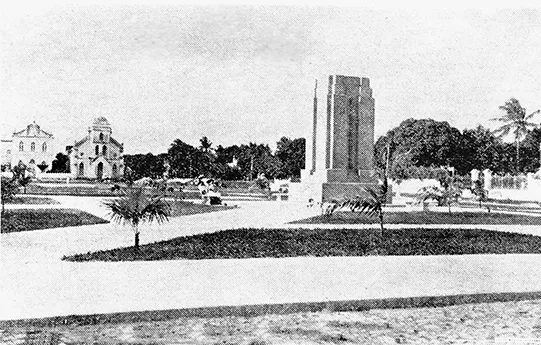

The Casa Forte Square was Burle Marx’s first project for a public garden. The garden was designed to occupy a space known as Campina da Casa Forte (campina is an area with no trees), delimited by an area of residential buildings constructed following the deactivation of an old sugar mill. The so-called Engenho da Casa Forte (Casa Forte Sugar Mill) was built in the mid-sixteenth century, and as early as 1645 the whole area was considered to be one of the best agricultural properties in Pernambuco (Costa 2001, 61). The Battle of Casa Forte took place at the Campina da Casa Forte during the same year, culminating in the expulsion of the Dutch from Pernambuco following the Portuguese colonization of Brazil. Later on, the plantation heirs handed over the area to the municipality to embellish the local church, to serve as a space for commercial fairs, and to perpetuate the memory of the Brazilian victory against the Dutch (Costa 2001, 65). In the early twentieth century, the place was used for local religious events and profane celebrations. It received a memorial plaque in 1918 and a monument in the 1930s, both upon the recommendation of the journalist and cultural activist Mario Melo (Melo 1935, 6, Silva 2010, 142) in order to pay tribute to those who lost their lives on the battlefield.

In the early 1930s, the Campina da Casa Forte comprised a narrow and long terrain, bordered by residential buildings, with a church in one of the extremities, and was already divided into three parts, as seen in the 1932 Planta da Cidade do Recife e Arredores (Plan of the City of Recife and its Surroundings). During the administration of the mayor Antônio de Góis (1931–1934), the area received the aforementioned commemorative monument in art deco style, art nouveau cement banks, and some garden works which included the plantation of at least two species of palm trees, coconut (Cocus nucifera) and Chinese palm tree (Livistona chinensis) (Silva 2017, 129).

Figure 1.1 Praça de Casa Forte (Casa Forte Square): monument erected in the 1930s to pay tribute to Brazilian soldiers killed on the battlefield in 1645, the church, flower beds, benches and palm trees.

Source: Annuario de Pernambuco para 1935, published in Silva (2010, 143).

In 1935, Burle Marx began to remodel the Campina da Casa Forte space. The Casa Forte Square, also called Casa Forte Park, was inspired, as the landscaper often mentioned, by the Botanical Garden of Berlin, photographs of Kew Gardens in London and by the Parque de Dois Irmãos (Park of Two Brothers) in Recife (Marx 1935c, 12, Marx 1985, 71, Hamerman 1995, 167). He conceived of three lakes, one in each section of the square, “subordinated, however, to a coherent ensemble” (Marx 1935c, 12). Each of the lakes per se performed a specific “educational function”, since they represented “an isolated group, based on the geographical origin of their elements”, as explained by Marx in his article “O Jardim da Casa Forte” (“The Casa Forte Garden”) published in Diario da Manhã (Marx 1935c, 12).

In the same text, Burle Marx mentioned that water – another of the main elements of his project – was an overarching element in the history of gardens and had never ceased to be used in Spain, France, Germany and Italy, adding that it was André Le Nôtre, the famous French landscaper, principal gardener of King Louis XIV and author of the Versailles Gardens, who had created for the first time large water surfaces which replaced “the parterre de broderie by the parterre-d’eau with the purpose of creating calm areas, new light and reflection perspectives and contrasts”(Marx 1935c, ...