eBook - ePub

A Brief History of the Future of Education

Learning in the Age of Disruption

Ian Jukes, Ryan L. Schaaf

This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

A Brief History of the Future of Education

Learning in the Age of Disruption

Ian Jukes, Ryan L. Schaaf

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

The Future Tense of Teaching in the Digital Age The digital environment has radically changed how and what students need and want to learn, but has educational delivery radically changed? Get ready to be challenged to accommodate today’s learners as opposed to allowing default classroom practices. With its touches of humor and choose-your-own-adventure approach, the book encourages readers to search for interesting, relevant or required material and then jump right in. At its core, readers will:

- Consider predictions about future learning.

- Understand how to leverage nine core learning attributes of digital generations.

- Discover ten critical roles educators can embrace to remain relevant in the digital age.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que A Brief History of the Future of Education est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à A Brief History of the Future of Education par Ian Jukes, Ryan L. Schaaf en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Pedagogía et Política educativa. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

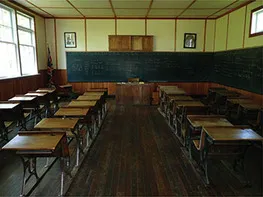

1 Beyond “That’s the Way We’ve Always Done It”

istock.com/Boonyachoat

The reason nothing important changes in education is because if one significant change is made, everything would have to change.—Ted Sizer

It is amazing how often people embrace doing things the way they have always done them without first carefully examining how or why a process came into use in the first place. We often accept a preexisting mindset because it is the path of least resistance. The mindset about the way educators organize schools is based on decisions made at the time of the horse and buggy, oil lamps, and factory production lines (Lapidos, 2007; Wagner & Dintersmith, 2015). Continuing to operate with that mindset is a classic case of that’s the way we’ve always done it (TTWWADI).

Schools haven’t structurally changed that much in a long time. But the world we live in is no longer the stable and predictable place it once was. Disruptive technologies have ignited an engine of change, and that rate of change appears to be accelerating with each passing day. Radical developments hold profound implications for life as we know it. In an environment of constant and disruptive change, it is critical that we begin to question the rationale behind the TTWWADI mentality in our schools.

A Preamble About Five Monkeys

In his research, Gordon R. Stephenson (1967) finds that TTWWADI was evident in our evolutionary cousins—monkeys. Envision that you have an enclosure containing five monkeys. From the top of the enclosure, hang a banana on a string, and place a set of stairs under the banana. Eventually, one of the monkeys will go to the stairs and start to climb toward the bananas. As soon as that monkey touches the bottom stair, you spray all the monkeys in the enclosure with cold water from a fire hose until you drive them away.

After a while, another monkey makes another attempt for the banana with the same results. Again, as soon as that monkey places its foot on the bottom stair, you spray all the monkeys with ice-cold water from the fire hose until it drives them away. Repeat this behavior until when one of the monkeys eventually attempts to climb the stairs to grab a banana, the other monkeys attack and prevent that monkey from climbing the stairs because they don’t want to get sprayed with the cold water from the fire hose. Another attempt, another attack. Another attempt, another attack.

In time, the monkeys all become conditioned, and they understand that if they try to climb the stairs to get the banana, the other monkeys will attack them. Once the monkeys are conditioned, you can put away the cold water and the fire hose. Next, remove one of the original monkeys from the enclosure and replace it with a new one.

Soon, the new monkey will see the banana and try to climb the stairs to get it. To that monkey’s shock and horror, all the other monkeys in the enclosure will attack the newest monkey because they do not want anyone to spray them with cold water. After repeated attempts and attacks, the newest monkey also becomes conditioned. The newcomer understands that if it tries to climb the stairs, the others will attack it.

Next, remove another of the original five monkeys and replace it with a new one. The scene will repeat itself. When the newest monkey tries to climb the stairs to get the banana, all the monkeys, including the first newcomer, attack the newest monkey, punishing it with the greatest of enthusiasm! Likewise, this happens when you replace the third original monkey with a new one and then the fourth and fifth.

Every time the newest monkey tries to climb the stairs, the others attack it. Interestingly, the monkeys that are beating the newest monkey have no idea why they are not permitted to climb the stairs to get a banana, nor why they are beating the newest monkey.

After replacing all the original monkeys, none of the remaining monkeys in the enclosure have ever been sprayed with ice-cold water from the fire hose. Nevertheless, no monkey will ever again attempt to approach the stairs to try to get a banana.

At this juncture, the critical question to ask is, “Why not?” The answer is, because as far as all the monkeys in the enclosure are concerned—that’s just the way they’ve always done it. This is the essence of TTWWADI, and our superior human brains do no more to insulate us from this behavior than do the brains of monkeys. (Authors’ note: No monkeys were harmed in the writing of this book!)

Why We Do the Things We Do

Do you have unconscious habits in your teaching practices? Do you ever stop to think about why you use a particular instructional pedagogy? Do you have the same rituals when you attempt to engage students in their learning? Do you have a routine as to how you start or end your class?

It is astonishing how easy it is for us to embrace doing things the way we’ve always done them without stopping to ask, “Why?” Often, this happens because it is much easier to continue going in the same direction than it is to reexamine the situation and reevaluate a decision or process. With all the effort required to think through an issue, it is all too easy to slip into a preexisting, fixed mindset. We choose to accept things as they are because it is the path of least resistance. In this section, we examine the true story of how Roman chariots dictated the dimensions of our modern railways and even influenced America’s space program. This exploration does not specifically relate to education and instruction, but it does crystallize our collective human tendency to live with established practices because it’s easier than changing them.

The Mindset of Railways

Before we reach back to Roman times, let’s start in the middle of the story. In the United States and many other parts of the world, the spacing between the rails on railroad tracks is a set standard—it is exactly 4 feet, 8½ inches (1.4351 meters). Now, some people might say 4 feet, 8½ inches seems to be a rather odd and seemingly arbitrary number. Why is it 4 feet, 8½ inches and not 4 feet, 6 inches or 5 feet, or some other random number? There are many theories, stories, and urban legends about this width, but the story that we like the best (whether it is true or not) is that 4 feet, 8½ inches was the track spacing that engineers in England used to build many of the first railroads, and it turns out that it was English expatriates who built most of the first U.S. railroads (Bianculli, 2001).

The reason England used a rail spacing of 4 feet, 8½ inches is that the same guild that had been building the horse-drawn wagons and handcarts in the prerailroad era in England also built the first English railways. It turns out that 4 feet, 8½ inches is the axle width the English wagon makers used to build the first railroad cars (Bianculli, 2003).

So, a question you might ask is, “Why did the wagon makers use that particular axle width of 4 feet, 8½ inches?” It turns out that they did this because they had to. If they used any axle spacing other than 4 feet, 8½ inches, the wagon wheels would almost immediately break on the sides of the established wheel ruts throughout England, which coincidentally also happened to be 4 feet, 8½ inches.

This begs the question, “Where did those old rutted roads in England originate?” It turns out that Imperial Rome made the first long-distance roads in Britain—and most of Western Europe, for that matter—more than two thousand years ago. They built these roads for their Roman military, and the roads have been in steady use ever since (Bianculli, 2003).

In fact, it turns out that Roman war chariots formed the initial ruts in these first roads; and it also turns out that the axle spacing of these chariots was 4 feet, 8½ inches. So, everyone ever since has had to adapt to those ruts to avoid destroying their wheels. Thus, it turns out the United States’ standard railroad track spacing of 4 feet, 8½ inches actually derives (this is a fact!) from the original specifications for an Imperial Roman war chariot from more than two thousand years ago (Bianculli, 2003).

Now some of you might be thinking, But that’s stupid, that’s ridiculous, that’s absurd, and you may be right. But here’s the thing—specifications, bureaucracies, institutions, and systems have a natural tendency to solidify in their ways of doing things. Often, they may require people to do things in the same way their predecessors have traditionally done them, despite the fact the world continues to change all around them.

So, in this situation, a question you might find yourself thinking is, What fool—what horse’s backside—came up with this way of doing things? In the case of the American railways, you’d actually be a lot closer to the truth than you could have ever imagined. Here’s why—it turns out Imperial Rome designed its war chariots to be just wide enough to accommodate the width of two horses’ backsides (Bianculli, 2003).

Indeed, it was a horse’s backside that originally determined the way we continue to do things more than two millennia later. So, now we finally have the answer to the original question—TTWWADI! That’s the way we’ve always done it!

Space Travel and Horses’ Backsides

The story doesn’t end with railroad track spacing and horses’ backsides. Although NASA has retired the space shuttle program, when we used to watch space shuttles rocketing off their launch pad, there were two big booster rockets attached to the sides of the main fuel cell. These were solid rocket boosters, which NASA had made at the ATK Thiokol Propulsion factory in Utah (Bianculli, 2003). If you had talked to the engineers who originally designed the solid rocket boosters many years back, they would have told you quite categorically that they wanted to make those solid rocket boosters a bit larger to get more thrust and, therefore, more lift at launch. The problem was that they had to ship the solid rocket boosters by train, 2,362 miles (3,801 km) from the factory in Utah to the launch site in Florida.

The railroad line from the factory to the launch site ran through various tunnels in the mountains. The tunnels were only slightly wider than the railroad tracks, and, of course, as we already know, those railroad tracks were only as wide as two horses’ behinds (Bianculli, 2003).

So, what was obviously a major design feature to what was and continues to be one of the world’s most advanced, sophisticated transportation systems—with more than a million moving parts at launch—was actually influenced more than two thousand years ago by the width of two horses’ asses.

TTWWADI and School Mindsets

In 1894, The Committee of Ten, a working group of primarily postsecondary educators from the eastern United States, recommended the standardization of the American high school curriculum (National Education Association of the United States, 1894). More than a century on, their recommendations continue to be the foundational principles upon which America’s public education system rests (Wagner & Dintersmith, 2015).

At the beginning of the 20th century, agricultural-age thinking gave way to industrial-age thinking. Frederick Winslow Taylor’s (1910) The Principles of Scientific Management became the basis for the modern assembly line. The employers of the time considered the factory model the most advanced form of organizational productivity possible. Not surprising...

Table des matières

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Introduction

- 1 Beyond “That’s the Way We’ve Always Done It”

- 2 What the Future Holds for Our Students

- 3 Life in the Age of Disruptive Innovation

- 4 The Nine Core Learning Attributes of Digital Generations

- 5 How to Look Back to Move Forward

- 6 Learning in the Year 2038

- 7 New Skills for Modern Times

- 8 New Roles for Educators

- Epilogue

- References and Resources

- Index

- Publisher Note

Normes de citation pour A Brief History of the Future of Education

APA 6 Citation

Jukes, I., & Schaaf, R. (2018). A Brief History of the Future of Education (1st ed.). SAGE Publications. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1485081/a-brief-history-of-the-future-of-education-learning-in-the-age-of-disruption-pdf (Original work published 2018)

Chicago Citation

Jukes, Ian, and Ryan Schaaf. (2018) 2018. A Brief History of the Future of Education. 1st ed. SAGE Publications. https://www.perlego.com/book/1485081/a-brief-history-of-the-future-of-education-learning-in-the-age-of-disruption-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Jukes, I. and Schaaf, R. (2018) A Brief History of the Future of Education. 1st edn. SAGE Publications. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1485081/a-brief-history-of-the-future-of-education-learning-in-the-age-of-disruption-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Jukes, Ian, and Ryan Schaaf. A Brief History of the Future of Education. 1st ed. SAGE Publications, 2018. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.