![]()

1 History’s fragments

The twenty-first century has signalled the explosion of documentary film practices in India. The rapid growth of film festivals across the country is one manifestation of this, with locations ranging from small urban centres to metropolitan cities, and from South to North India. With a special focus on documentary film, these festivals overlap in time with each other and attract multiple audiences. Whether funded by local non-governmental organisations, international aid agencies, universities, film societies, collectives of friends or local or national governments, film festivals have become the sites of interaction for filmmakers and a diverse Indian audience. They are new public fora in which to engage with social issues, organise political actions or simply be entertained against a backdrop of issues of social relevance. Special seminars and post-screening discussions feature at most of the festivals. Stands selling books and DVDs, together with food and tea stalls, act as arenas of interaction between screenings for both audiences and filmmakers. Filmmakers create the dynamics of the festivals by talking about their films both after the screenings and during breaks and seminars. They connect with each other through discussions about other films and filmmakers, and also by answering questions from the public and creating a dialogue with interested participants. On these occasions, filmmakers’ concerns are often about whether the festival has a good crowd, whether the public has responded with interesting questions and/or whether their films have opened up an enriching audience discussion. In contrast, audiences’ concerns are about whether the films were of social relevance and whether they were interestingly made. Indeed, film festivals in India are the places through which documentary film enters Indian public debate and sets up a ‘dialogue’ with the audiences through its form and content. They are the places in which filmmakers witness, mediate and endorse this dialogue. In short, they are the ‘concrete’ sites wherein we can recognise the existence of a well-established film practice in constant dialogue with its active audience.

This might be a familiar scene and an easily convincing argument for all those who have participated at least once in a contemporary documentary film festival somewhere in India. Yet, to understand the scale and complexities of contemporary documentary practices it is necessary to look back at the past and with contemporary eyes try to identify the historical legacies that, even if often neglected, persist in the present day. Indeed, how did it all begin? In order to address this question, this chapter explores the colonial period as one of the key moments in the development of documentary film practices in India, but also as the most neglected moment in terms of finding connections with contemporary practices.

During my 2007–2009 stay in India, many of my interlocutors refused to recognise any possible association between contemporary documentary practices and the colonial period. They identified the beginning of contemporary independent filmmaking as being as recent as the late 1970s and early 1980s – when individuals such as Anand Patwardhan began making state-independent films and screening them for an Indian public, and when video technology was enabling documentary films to circulate more freely across the country (cf. Chapter 4). The extensive colonial period of approximately 50 years of filmmaking has never been considered part of the history of contemporary documentary practices. By and large, it has been seen as a period of neither creativity nor self-determined politics; rather, according to my interlocutors, this ‘moment’ of history was simply synonymous with ‘war’ and ‘propaganda’. Why was this the case?

In the early 1980s, the Subaltern Studies Group came together to criticise the elitism of the historiography of colonial India and to provide ‘other historiographical points of view and practices’ (Guha 1988: 43). This chapter (and the one that follows) aims to do something similar in relation to what I shall call ‘the nationalist historiography of documentary films’. While searching in a number of different archives for scattered and patchy documentation of this historical period, I came across a series of accounts which, while talking about the documentary productions of Independent India (cf. Chapter 2), also contributed to what, at the time of their writing, was for them the development of documentary film productions during colonial India, thus influencing the contemporary perception of this historical moment.1 These accounts consider Indian documentary as a ‘war baby, conceived by the British and nurtured by the Indians’ (Garga 1987a: 25), leaving out of their discussions other elements that today are considered useful for a better understanding of the genealogy of a variegated scene of contemporary documentary practices. Among these accounts, I shall single out those of B.D. Garga, Jag Mohan and Sanjit Narwekar, whose writing on this subject has been extensive.

Arguably, B.D. Garga’s contribution has been the most detailed. In several 1987–1988 articles for the film quarterly Cinema in India, and in his more recent book, From Raj to Swaraj (2007), he has presented a thorough history of film institutions during World Wars I and II (henceforth WWI and WWII). Garga was able to do this thanks to the help of an individual who was influential in the late 1930s and 1940s, J.B.H. Wadia. During WWII, Wadia worked as the chairman of a film institution called the Film Advisory Board, set up by the British government of India. In 1980, Wadia donated to Garga ‘three thick files neatly marked “Film Advisory Board 1940–41–42”’ (Garga 2007: ix). As Garga himself states, these files comprised ‘official correspondence, minutes of meetings, the yearly programme, and notes on films and persons’ (ibid.) and they became the central unit of his historical analysis. Garga’s contribution thus provides a unique view of the history of documentary film in colonial India. However, his approach does not critically interrogate the collected data nor does it consider wider sources beyond the donated files.

Similarly, Jag Mohan neglected to explore, or compare his findings with, other historical sources. He entered the documentary scene in India, thanks to the influential personality of Dr P.V. Pathy, who convinced him to move from Madras to Bombay and participate in the emerging documentary scene. Mohan never became a filmmaker; however, he worked as a scriptwriter and a film critic in close contact with filmmakers. From the late 1940s, Mohan wrote about documentary film in India, relying exclusively on his own first-hand experience of the filmmaking scene and hence making the activities of Independent India more central in his analyses than those undertaken in colonial India. In other words, his account provides a history similar to that presented by Garga – that is, written from a ‘nationalist’ perspective and not sufficiently analytical regarding the colonial moment.

More recently, Sanjit Narwekar has also begun to write about documentary in India. Narwekar has always worked closely with the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) and the state-run Films Division, and in turn has relied rather unquestioningly on both Garga’s and Mohan’s historiographies. Since the early 1990s, Narwekar’s writings have served as key sources for the government of India, which, in 1996, decided to make a film about this history, entitled Through a Lens Starkly (Khandpur 1996). This film is today part of the Films Division collection and contributes to a particular nationalistic view of both colonial and Films Division documentary. Over time, Sanjit Narwekar has continued working and writing in collaboration with the Films Division. When, by chance, I bumped into him while conducting research in the NFAI library in Pune, he confidently told me, among other things, ‘… Even today the so-called community of documentary filmmakers exists thanks to the Films Division’.

Scholars interested in postcolonial India (cf. Chatterjee 1994, 1995; Roy 2003, 2007; Sarkar 2009; Jain 2013) have occasionally paid attention to the film activities undertaken by the Films Division with the gaining of Independence (cf. Chapter 2); yet they all begin their discussion from the history of colonial India provided by the aforementioned authors. After consulting sections of the Indian Cinematograph Committee Report, 1927–1928; the Indian Cinematograph Committee Evidence, 1927–1928; and the Handbook of the Indian Film Industry, 1949 – all directly connected to documentary films produced and circulated in colonial India – I came to understand that the history provided by Jag Mohan, B.D. Garga and Sanjit Narwekar was, in reality, only a limited history and that it needed to be critically questioned. ‘Film history, like every field of history, has its points of amnesia’, writes film historian Stephen Bottomore, and early ‘non-fiction’ film is, without doubt, one of the areas that scholars have often overlooked (1995: 495).

By searching for what Bottomore calls ‘points of amnesia’, this chapter will make use of the Foucauldian approach of ‘effective history’ and critically challenge the accounts that contributed to the nationalist historiography of documentary films. To do this, it will make use of other ‘historical fragments’ I encountered during my research. As ‘disturbing element[s], a disturbance, a rupture … in the self-representation of particular totalities and those who uncritically uphold them’ (Pandey 2006: 66), the ‘historical fragments’ presented here will seek to rehabilitate the colonial period as something more than just war and propaganda. Presented in a non-chronological way, this approach will enable us to open up a critical discussion about a genealogy of documentary filmmaking in India that will be a more useful tool for grasping a multitude of contemporary documentary practices.

Discursification of colonial film productions and activities

When I had the chance to converse with Gargi Sen for longer than our usual hurried interactions, she was astonished to hear that I was interested in analysing contemporary filmmaking practices through a colonial lens. When I passed on this information to her, she was sitting beside me in front of her office computer and abruptly replied, ‘Why the “colonial”? It was all about war and propaganda!’ After saying this, she searched through her files on the computer and forwarded me an essay about Nazi cinema that she had written some time before. Then she added, ‘you mention Paul Zils, but he was simply a filmmaker associated with Nazi cinema’.2

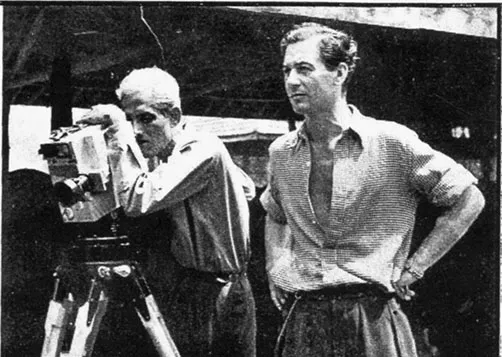

This statement might sound like a clear-cut radical position that leaves no space for further interpretations; strikingly though, at the time of my 2007–2009 fieldwork, Gargi Sen’s opinion was not exceptional. Several other filmmakers provided me with a similar reading, which was precisely the perspective presented in the nationalist historiography of documentary films. This historiography describes Paul Zils as a filmmaker who began his career in Germany as ‘a favourite of Goebbels [Hitler’s minister for propaganda] because of his handsome blond looks and “full Aryan credentials”’ (Garga 1987c: 34). He was a German, who started his filmmaking career as an apprentice at the Universum Film Aktiengesellschaft (UFA) in Berlin in 1933. Due to his obsession with Asia, which began when he read Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha, he decided to travel the world and, consequently, he found himself working in Hollywood, Japan and Bali. Jag Mohan narrates that while Zils was in Bali, ‘a ship in which he was travelling was hit by a submarine…. He was lucky to survive but he was rounded up as a prisoner-of-war and brought to India’ (1972: 44). The British sent Zils to a detention camp in Bihar where other Germans and prisoners of the Indian freedom struggle were located. As Zils himself narrates, in this context he had the chance to meet a number of people and become friends with several influential personalities who introduced him to Buddhism, Indian dance, Indian theatre performance, Indian films and the reality of Indian life (1955: 8). Garga points out that, thanks to his idea to organise musicals at the camp, the British noticed Zils (1987c: 34). Hence, they offered him a position at Information Films of India (henceforth IFI), one of the WWII film institutions. Here Zils met Dr Pathy, a leading Indian filmmaker from the mid-1930s. As soon as the IFI had closed down, with the end of WWII, Zils began working with Dr Pathy on a film called India’s Struggle for National Shipping (see Figure 1.1), sponsored by the Scindia Steam Navigation Company. The film was about Jawaharlal Nehru’s politics and the message of freedom that he addressed to the newly formed country (see also Vidal 2003a, 2003b). This film was released in 1947 and screened in cinema halls the week following Independence (Zils 1955: 5). According to the accounts of the nationalist historiography of documentary films, this moment signalled the beginning of the ‘Indian documentary’. This is the point from which many others have constructed their narratives about the documentary film practices of this period (cf. Chatterjee 1994, 1995; Roy 2003, 2007; Raghavendra 1998; Sarkar 2009; Jain 2013), which in turn have fed into a number of contemporary opinions about this historical past.

Figure 1.1 Shooting: Dr P.V. Pathy working with Paul Zils in Indian Documentary.

Source: courtesy of the IDPA.

In contrast to Gargi Sen and others, at the time of my 2007–2009 fieldwork, Vijaya Mulay (or Akka), who worked with Zils in the early 1950s, associated the name of Paul Zils with the revolutionary time of the ‘Indian documentary movement’. When I met her in her house in New Delhi, she was 88 years old and a veteran of documentary film practices in India.3 As soon as she started conversing with me she said, ‘When Jag Mohan and Paul Zils were there, it was a revolutionary front for the documentary movement’. She went on, ‘both Paul Zils and Jag Mohan should be considered as part of the historical moment of the FD and the IDPA, which together contributed to the development of documentary film in India’.4 The Films Division (FD) and the Independent Documentary Producers Association (IDPA) were two important institutions for the development of documentary film soon after Independence and individuals such as Paul Zils, Dr P.V. Pathy and Jag Mohan should be considered to be among the independent actors of the colonial period who fostered this development.

Nevertheless, while the accounts of the nationalist historiography of documentary films pay attention to these individuals, they do so in function to the historico-political context of their own present moment of writing (that is, the recently attained Independence) rather than in relation to the specific historico-political context in which these practitioners emerged and practised filmmaking. By so doing, these accounts limit their descriptions to the ‘exceptionality’ of these individuals, often in relation to war institutions (as in the case of Paul Zils). War institutions indeed, are considered in this historiography as the most important agents for the emergence of the Films Division in Independent India.5

The conventional argument contained in the nationalist historiography of documentary films is that documentary in India is a ‘war baby, conceived by the British and nurtured by the Indians’ (Garga 1987a: 25). In relation to this belief, the accounts of the historiography narrate that, thanks to the establishment of war institutions, India expanded its documentary production dramatically. Through these institutions, a great number of men received technical training, acting as the key agents for the development of the documentary in India. In addition, the accounts of this historiography argue that thanks to new regulations, issued during wartime, for the first time documentary film began to reach an audience in India through compulsory exhibition in cinema halls. Indeed, the government issued an order, under rule 44A of the Defence of India Act, which made war films, with a minimum running time of 20 minutes, compulsory for every cinema exhibitor (cf. Mohan 1960, 1969, 1972, 1990; Garga 1987a, 2007; Chanana 1987; Narwekar 1992; Varma 1998).

According to P.V. Pathy, the wartime period of documentary film in India began ‘in the twilight of the nineteen-thirties, some six months after the outbreak of the Second World War’ (in Mohan 1972: 64). As he narrates, ‘the then Government commissioned the production of two or three documentaries, destined for propaganda, related to the needs of War Effort’ (ibid.). The films were about the Royal India Navy, the India Air Force and the way in which Nazis were compelling ‘Indian students living in Berlin to broadcast lies to India’ (Garga 2007: 63). They were war productions, but under the guidance of Wadia Movietone. At that time, Wadia was a respected figure in the film industry and, according to Garga, well-known for his anti-fascist views. Before long, the government asked Wadia to serve as chairman of the Films Advisory Board – a film-institution that formally came into existence in July...