![]()

Chapter one

Japan: A well-ordered society

In an article on Japanese Vocational Education and Training written a few years ago,1 I commented on the fact that, given the astonishing post-war success of Japan's economy and its effects on its principal competitors, including the United Kingdom, it has been inevitable that we should seek reasons for that success and, where appropriate, emulate them. There is a widespread belief that an important contributory factor has been the Japanese system of vocational education and training, and it is the purpose of this chapter to describe and analyse that system and to judge whether that belief is justified.

Until relatively recently, however, very little has been written on the subject in The United Kingdom, and it was as late as 1984 that interest in it was stimulated in both educational and industrial circles, by the Report of the Institute of Manpower Studies, Competence and Competition, which reviewed vocational education and training policies, not only in Japan, but also in the Federal Republic of Germany and the United States.2 To its own satisfaction and to that of many others, the Report, which was commissioned by the Manpower Services Commission (MSC) and the National Economic Development Organisation (NEDO), demonstrated what it called 'the central importance of vocational education and training in the development, production and selling of high quality, competitive products and services'. Its findings generated widespread discussion, and, as a result, comparisons have been drawn between the inadequacy of the British system of vocational education and training, and the effective programmes of major industrial competitors, including Japan. Another Report,3 published two years later by the Society of Education Officers, based on a short visit to Japan in February 1986, reinforced the findings and recommendations of its predecessor.

The social background

One of the major difficulties that the authors of these reports faced was in trying to understand properly the cultural and social context of the countries under examination, particularly in the case of Japan, whose values and attitudes are so different to those widely found in developed countries in the west and where language differences pose formidable barriers, especially as both reports were based on visits lasting little more than two weeks. Nor would I claim much greater understanding, even though I lived in Japan and extensively examined Japanese vocational education and training for a period of four months in the Autumn of 1985. There is, however, a growing volume of literature both on Japanese society in general, and on its educational system in particular, mainly by American scholars, and three very informative books which are particularly to be recommended to those who wish to inform themselves more fully on these subjects, are Christopher's The Japanese Mind: the Goliath explained, Duke's The Japanese School, and Rohlen's Japan's High Schools.4

What then are the major cultural and social features of contemporary Japanese society which determine and influence their system of vocational education and training, as identified by these and other authors and which, indeed, are there for any percipient visitor to Japan to see? In some ways, perhaps the most significant is the widespread recognition of the need to utilise to the full the talents and abilities of the Japanese people. Japan is a country three-quarters of which is mountainous and uninhabitable, so that its population of 120 million is crowded into about 80,000 square kilometres, one-quarter of its total land surface of 378,000 square kilometres, and less than half the total land area of the United Kingdom. Moreover, it possesses very few natural resources, so that in order to survive it has to import large quantities of major raw materials such as oil, coal, iron ore, cotton, and wool, as well as wheat and other foodstuffs. Indeed, its only major resource is the talent of its people, which, it is generally agreed, must be developed and used to the full. This attitude is fostered by the relative social homogeneity of its population and by deep-rooted historical factors.

Japan's ethnic and social homogeneity is one of the features that most strikes the visitors: there is a virtual uniformity of skin and hair colour, for example, which is a marked contrast to the multi-ethnic societies of the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom. Foreigners, known to the Japanese as Gaijin are few and far between, especially outside the large cities: when my wife and I, for example, visited a small, rural primary school on the west coast of the main island, Honshu, we were told by the headmistress that we were the first westerners the children had seen. More significantly, perhaps, the only ethnic and social minorities are relatively small groups of Koreans, Ainu (natives of the northern island of Hokkaido), and Burakumin, or outcasts. The Koreans, who number fewer than 100,000, have lived in Japan for many years, but have been made to acquire Japanese nationality and are discriminated against in a variety of ways. The Burakumin, who to all outward appearances are indistinguishable from the rest of Japanese society, used formerly to live in ghettos but are now scattered about the country. They, too, suffer discrimination in a variety of ways, and tend to be restricted to less sought-after and more menial jobs. Recently, however, both groups have reacted more strongly against the somewhat scornful attitude of Japanese society and are increasingly demanding to be treated on a par with Japanese at large.

In many paradoxical ways, Japanese society is both much more hierarchical and classless than those in the west. The sense of hierarchy is well-developed on a personal level, determined by such factors as age and position in a company or educational institution, and manifested openly, for example, by the subtle ways in which Japanese address each other and the depths of their bows. On the other hand, the Japanese frequently claim that theirs is a classless society in which educational and other opportunities are equally available to all. To an extent this is true, as we shall see in the case of the educational system, and what Christopher calls 'some of the more obvious benchmarks of social class' in the West are missing in Japan: workers and university professors are likely to speak with similar accents and read the same newspaper, for example. On the other hand, there are clearly notable differences in the behaviour and standard of living of different groups in Japanese society which are linked to economic, educational and occupational status.

Another striking and immediately apparent feature of Japanese society is that it is socially cohesive and, perhaps as a consequence, extremely well-behaved. Anti-social behaviour is rare and frowned upon and it is possible, for example, to walk in any large city in Japan, at any time of day or night, without fear of molestation. This may also be a reflection of the fact that Japan is a very crowded, urbanised society. The great majority of its people live in large, very densely packed cities in which space is a premium, living space is extremely limited and very expensive, and where good social behaviour is essential to public order. By western standards, the cities are largely unplanned and visually nondescript and sometimes ugly — they were virtually all destroyed during the war and have since been rebuilt in the modern architectural vernacular. They have also greatly expanded, attracting many people from the countryside into Japan's booming industry and business, and seemingly go on for ever. On the other hand, for those who live in Japan's cities, their seemingly unending sprawl is humanised by falling into relatively small districts, each with its market area composed of stalls and small shops — the density of the cities for the most part obviates against chains of large supermarkets in the western idiom — and, more often than not, its temple. Above all, for foreigners at least, living in a large city is made more than bearable by the friendliness, warm hospitality and grace of virtually all the Japanese whom they encounter. It is one of the many paradoxes of Japan that it has permitted its cities to become visually ugly while retaining its love of simplicity and beauty in its gardens and, frequently, its house interiors.

Another reason for its relative social tranquility is the prevailing attitude, common also in China from which Japan has inherited much of its culture, which regards membership of a group as all-important, in sharp contradistinction to the much more individualistic attitudes adopted in the west. Indeed, membership of a group is seen as enhancing the importance of the individual so that there is little or no feeling of resentment at the loss of individual identity. In any case, as we have seen, individual identity and one's place in the scheme of things can be expressed in many subtle ways. It was pointed out to me by an American who was married to a Japanese wife, and who taught in one of the most prestigious Japanese universities, that the more reticent attitudes of the British were much more acceptable to the Japanese than the outgoing behaviour of the majority of Americans. The importance attached to being a member of a group was also brought home in another way: on visiting one of the technical colleges run by the Hitachi corporation for its employees, I was observing part of the training of a group of young graduates, recently recruited in strict competition from all over the country, who had embarked on a fifteen-month residential course, living in purpose-built accommodation. I was informed that, during the fifteen months, they were entitled to ten days holiday to return to their families if they wished, but many of them did not take it all up, preferring to spend their leisure time with their colleagues. This attitude, which admittedly is showing some signs of changing in the younger generation, breeds loyalty to companies and greatly reduces the likelihood of industrial dissent.

Along with the loyalty displayed by workers towards their companies, one frequently finds paternalistic attitudes adopted by many large companies towards their employees. This accounts for the strong tradition of 'life-long employment' which, to a limited extent, still prevails in certain grades in all large organisations, and for a wide range of company-provided fringe benefits. These attitudes, together with the national importance attached to developing the abilities of Japan's human resources, combine to lead Japanese companies to invest very heavily in industrial training and retraining. Indeed, of the total expenditure on industrial training in Japan, approximately three-quarters is provided by industry itself, and only one-quarter by the public sector.5

However, Japanese industry and business have been under increasing strain during the past few years. The combination of the rapid rise in the value of the yen, to which the term endaka is applied, has resulted in labour costs in Japan greatly exceeding those in countries like Korea, Taiwan and Singapore which are emerging as industrial rivals. One consequence has been a slow but steady rise in unemployment, which officially was running at just over 3 per cent in mid-1987. However, this figure conceals the fact that if the British method of calculating the rate of unemployment were used in Japan it would be at least twice as high there, as anyone who works for even a short period in the week is considered to be employed. Characteristically, the Japanese have responded to this situation with vigour. On the one hand, they are endeavouring to reduce labour costs by extending the use of automation and information technology. On the other, in keeping with the country's group psychology, Japanese industry is very reluctant to lay off their workers and instead, with government financial and other assistance, resort to measures such as transferring redundant workers to other companies, giving them longer holidays, and helping them to obtain other jobs.

It is worth commenting upon the fact that the skilled worker in Japan is expected not just to develop expertise in one skill to the exclusion of all others, but to be both adaptable and flexible in his attitude and skills in order to contribute more fully to the prosperity of his company. For this reason, Japanese industry provides both initial and retraining programmes. This combination of 'in house' education and training and social attitudes among employees, which has deep historical roots, results in a homogeneous corporate climate which often reaches religious or spiritual intensity.

There is a widespread acceptance in Japan, both by industry and the community at large, of the need for state facilitation of vocational training and, indeed, of a high degree of centralised control of the educational system. Thus, there is a long tradition of government involvement, both in establishing national economic goals, and in setting up and overseeing a framework of industrial training and development. The national statutory framework and administrative structure for industrial training are complex and based primarily upon the Vocational Training Law of 1969 and its subsequent amendments which lay down the fundamental principles of vocational training and make provision for the roles to be played by the various parties concerned with these activities.

Perhaps the major feature of this framework is that the primary responsibility for providing vocational training rests with industry, and the state, through the Ministry of Labour, assists in this process in a variety of ways, by, for example, providing substantial subsidies to encourage smaller companies to provide the necessary training. The government also oversees a national system of trade testing which has been in existence since 1959. It now extends to no fewer than 102 trades and operates at two levels, Grade I (more advanced) and Grade II. The tests are provided once a year and are a considerable stimulus to workers to undergo additional training, as successful completion frequently leads to promotion or preferment, as well as being a matter of individual pride.

However, one of the less attractive features of Japanese society, to the western observer at least, is its domination by men and the relatively low priority which it accords to the education and training of women. As a result, with few exceptions, however able and well-qualified academically women may be, they remain outside the mainstream of Japanese industrial and public career opportunities. Where they are employed by large corporations, they are often treated as temporary employees and expected before long to marry and leave the company. Many women work for smaller, less prestigious companies where they receive lower salaries than men, have less job security and less opportunity for training or educational development. To a considerable extent, the Japanese executive's ability and willingness to dedicate himself to his company depends upon a willingness on the part of his wife to forsake a career for herself and concentrate upon maintaining a house and raising children.

However, while it would seem that for the vast majority of Japanese women, marriage and child-bearing remain life's principal objectives, there is an increasing minority of younger women, especially among university graduates, whose aspirations extend beyond the home into a career. Moreover, the government recognising these legitimate aspirations, introduced recently an Equal Employment Opportunities Law, which has encouraged some companies to recruit more women university graduates for posts of equal status to those available to men. In addition, new maternity leave arrangements make it easier for women in jobs to retain them after child-birth. However, there are strong cultural pressures still making it difficult for women to pursue careers on equal footing with men and many women themselves prefer not to seek out senior positions but are content with jobs of lower status and salary which at least are free from the long working hours and considerable pressures inevitable in managerial posts in Japan.

The educational background

From a governmental point of view, Japan, is, by British standards, a highly centralised society. Although, for administrative purposes, the country is divided into municipalities and prefectures, roughly equivalent to British metropolitan districts and shire counties, and individual Japanese take pride in their allegiance to individual prefectures, nevertheless the writ of government ministries in Tokyo runs powerfully over the country as a whole. In the case of the school system, for example, the Ministry of Education (the Monbusho) lays down national guidelines for school curricula, in order, as it puts it, 'to ensure an optimum national level of learning, while at the same time adhering to the principle of equal educational opportunity'. In other words, a national curriculum has been a feature of Japanese schools for many years.

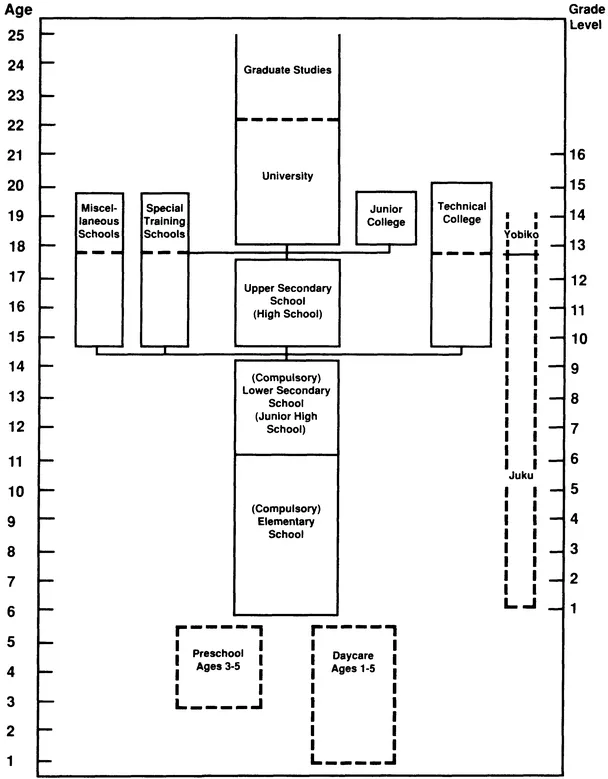

For individuals, however, perhaps the most important feature of contemporary Japanese society is its obsession with education. In the words of an American observer of the Japanese educational scene, 'It would be difficult to identify a country with a greater historical or contemporary zest for learning than Japan'.6 This obsession manifests itself in a fiercely competitive educational system, starting at kindergarten, proceeding through nine years of compulsory elementary and lower secondary school from age 6 to 15, and then on through upper secondary school (15 to 18) to university, junior college, or post-secondary vocational institution (see Figure 1.1). Thus, although the structure of the education system closely mirrors that of the United States, having been imposed on the country shortly after the war by the American occupation forces, in spirit and practice it is very different. Japanese schools have a very demanding curriculum, prescribed for them by the Ministry of Education, and in order to follow it they are required to operate an educational programme for at least 240 days each year. In most cases, therefore, children attend school six days a week for over forty weeks a year and are thus required to spend more time at school than in virtually any other country in the world. During their years of schooling, Japanese children achieve high levels of accomplishment in their native language and in mathematics, and acquire habits of diligence and perseverance which, in Duke's view, and that of many other observers of the Japanese scene, equip them extremely well as 'future workers'.7

In order for students to enter the elite post-secondary institutions, which are themselves highly calibrated — the most prestigious institution of higher education in Japan is, for example, the University of Tokyo, and within that establishment the most highly-regarded faculty is that of Law — students must obtain high grades in the 'best' elementary school, in order to obtain entry to the 'best' lower secondary school, and so to the 'best' upper secondary school. At lower secondary level, over 96 per cent of the schools are run by local education authorities, so that private schools are relatively uncommon for this age group. They are more numerous, however, at upper secondary level where they constitute about 28 per cent of all the schools. However, some of the most highly regarded schools are six-year privately run secondary schools which span the age range of both lower and upper secondary schools.8 Such schools, which cater for only a tiny minority of Japanese children, are rather like English public schools, and the competition to enter them is very fierce. The students in these schools compete for the limited number of places in the elite universitites, and study extremely hard to

Figure 1.1 The educational system in Japan

prepare for university entrance exams. There are no national examinations for entry into higher education; instead, they repeatedly take mock examinations which are specially prepared by companies which specialise in their production. The results of these examinations are scored by computer and sent to the students and their parents so that they know exactly where they stand in comparison to other children and how good, or bad, their chances are of getting into one of the top universities. Entry into university is determined by a system of vigorous entrance examinations, popularly known as 'examination hell'. This consists of two stages: a one-day standard university examination given throughout the country; and a two or three day's examination set by individual universities and covering perhaps as many as eight different subject areas. A place in the best universities offers the best career prospects, usually with one of the great industrial corporations, or with one of the ministries of state. ...