1 Healing the Self Model

As noted in the Introduction, the Healing the Self model can be a powerful way to deal with anger and violence in children with low self-esteem through the formation of meaningful relationships with educators and caregivers. The model suggests that because children develop through relationships, the relationship itself is the intervention for aggressive behavior; what adults do specifically in their efforts to help children control their behavior isn’t as important as their ability to connect with the child in a meaningful way.

Teaching educators and other caregivers how to meaningfully relate to aggressive and violent children is the foundation of the Healing the Self model. The approach is based on the assumption that relationships need not be traditionally “therapeutic” to help children—teachers, mentors, principals, and others can provide children with the necessary ingredients to build and maintain self-esteem through their school-based relationships. The Healing the Self model introduces evidence-based therapeutic approaches to non-therapists demonstrating how to:

- Establish themselves as an admirable role model

- Take an empathic stance with children

- Create a sense of belonging

The Three Relational Components of the Healing the Self Model

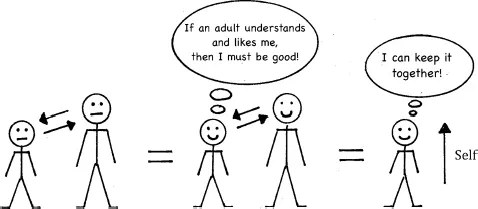

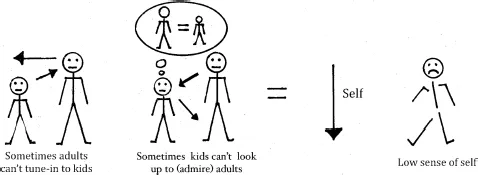

Research shows that children’s self-esteem is not based on their aptitude, abilities, or their current mood, but instead is a direct result of their relationships with important people in their lives. Typically, these relational needs are met in early childhood, and as the child matures and enters school, the foundation is laid for them to psychologically expand their capacity for relationships with others. For some children, however, these needs, sometimes despite the good intentions of adults, are not met. When this occurs, many children behave in ways that demand the attention of teachers, therapists, and other adults in an ultimate effort to drive the primary caregivers in the child’s life to meet those needs.

Educational and clinical experiences suggest that good teachers and therapists naturally try to meet their students’ and clients’ emotional needs. However, as the Healing the Self model teaches, in order for a relationship to help a child heal from developmental gaps, restore or build self-esteem, and reduce the expression of anger and violence, it must include three ingredients:

- Idealization

- Empathy

- Belonging

By understanding and applying these core ingredients to relationships, care providers can share a common language as they work to develop strategies that can help children. In the next three chapters, we will explore each of these three interrelated ingredients in greater detail. Learning activities designed to allow adults to better understand and more effectually apply these concepts will also be presented within these chapters.

Commonly Accepted Definition of Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is important, foundational, and necessary for children to control their emotions and their behaviors. But what is it? How and why does it support emotional stability? And what can teachers, therapists, childcare providers, and parents do to help children develop it?

Self-esteem is generally considered synonymous with how someone feels about himself or herself. According to the Mayo Clinic, “Self-esteem is shaped by your thoughts, relationships, and experiences” (Mayo Staff, 2014). Self-esteem can involve a variety of beliefs about the self, such as the appraisal of one’s own appearance, emotions, and abilities. Self-esteem is also important because it lays the foundation for how a person treats others and allows others to treat them.

Expanded Definition of Self-Esteem

Rather than thinking of self-esteem as primarily someone’s appraisal of his or her own ability, research has expanded the notion of self-esteem to encompass the broader idea of a sense of self. In general parlance, the term describes a person’s sense of self-worth. But self-esteem isn’t simply how people view themselves—it is the vantage point from which they view themselves, others, and everything around them. It is a person’s main driving force. Most people have a cohesive, enduring, internal core that allows them to understand themselves, others, and reality, and this can be considered as their sense of self (Ornstein, 1998).

Although technically difficult to define, self-esteem is a theoretical construct that is used to conceptualize many enduring personality traits. Self-esteem also serves to attract people who are similar. Moreover, most people are never psychologically alone, because in their minds they have internalized the traits of many others. In the case of children, self-esteem is what enables a child to appropriately feel emotions, control behavior, and make friends.

Children have specific psychological needs, including the need to admire other people, although this need changes over time. Children also need people to validate their construction of reality and they need to belong. This need to belong drives them to make friends and associate with other people whom they can experience as similar to themselves. When these needs are met, the relationships and interactions that fostered them are absorbed into the person’s personality or self (Socarides & Stolorow, 1985). In this sense, having a healthy self requires other people.

A sense of self or this expanded “self-esteem” is gained through relationships. This occurs most commonly in childhood through the relationship with the parent(s). Typically, children admire their parents and experience their parents as being like them. Parents validate the child’s experience and thus the parent and child feel deeply connected. In the child’s mind, this mixture of sameness, admiration, and connection generates feelings of security, self-worth, and confident aspiration (i.e., self-esteem). “If mom loves me,” the child thinks, “I must be lovable.”

But it can sometimes be very difficult to understand exactly what a child needs in order to feel connected to important adults in their life because children, especially young ones, live in a fantasy world. Children base their emotions on their imagination. One only needs to ask a preschooler if she rode a dinosaur to school and receive a smiling “Yes” to confirm that adults and children do not occupy the same reality. Children live in the world of pretend. Ultimately, meeting a child’s psychological needs requires entering that pretend world. Unfortunately, of course, some children’s needs are completely unmet—or worse—because adults are unable to enter this world. Caregivers may believe they are meeting a child’s needs, but if in the child’s mind the unspoken need isn’t met, it isn’t met. Although no one is at fault, the child may have deficits in his or her sense of self.

Understanding the Anger/Violence/Self-Esteem Trio

When a child’s psychological needs are not met, anger and violence are often the result. Anger and violence are directly related to self-esteem (Donnellan, Trzesniewski, Robins, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2005). The American Psychological Association generally considers anger an emotion children have when they feel they have been wronged or misunderstood. Anger is a feeling that children experience in their minds and bodies. They may sweat and have an increased heart rate. The may feel hot, dizzy, have a stomach ache, or exhibit any number of physical signs. In its most basic sense, anger is a feeling.

Violence or aggression, on the other hand, is a behavior. It is an action intended to harm another. Although seemingly similar to assertiveness, aggression differs in important ways. Anna Ornstein, an internationally known psychiatrist, explains that the foundations of aggression are feelings of “fear, distress and hostility; [w]hereas the foundation of assertiveness is feelings of joy, interest, and excitement” (Ornstein, 1998, p. 55). Although easy to confuse, at its root aggression is very different from assertiveness. Most childhood aggression is out of anger (Family Life Development Center, 2001). Anger is the feeling that causes most children, and many adults for that matter, to behave aggressively. Anger is the emotional fuel for aggression. Aggression differs from anger, because it’s not a feeling—it’s a behavior. A child feels angry but behaves aggressively.

Healing the Self Case Study: I’m a Soldier

David was a 10-year-old boy who read well and loved math. He was active and very well-spoken. Intellectually, he was way ahead of his peers. David, however, suffered in a world populated with grown-ups that didn’t behave well. Family illness, finances, relational difficulties, legal troubles, and substance abuse issues made his home a battle ground. Further complicating matters was the fact that the community was well aware of his family’s struggles. David refused to engage with peers, complete school work, or participate. He had no friends, isolated himself, and when he wasn’t yelling, he kept to himself with head hung down. When he did talk, he screamed “I’m angry,” and when invited to process, told complex, exaggerated tales that emphasized his intellect, power, or specialness. David told tall tales and adamantly reminded everyone that in the second grade he had been a soldier and was very dangerous. He didn’t let anyone know the real David, just the super tough, false, phony David.

Faculty wondered if his tales of grandeur were his best attempt at hiding both himself and a deep sense of shame that alienated him. His teachers focused on empathizing with David regarding the meaning of his stories, rather than proving he was wrong, and playfully joined him in his story telling. Of course David hadn’t walked on the moon, but what did his stories mean? David’s teachers agreed to use the Healing the Self model and refrained from challenging his stories. They attempted to deeply understand him. Maybe David felt scared, vulnerable, and boring, so identifying with being a soldier made him feel brave, tough, and exciting. Faculty developed the plan that whenever David needed to talk, he could step away and check in with the co-teacher, Lars. As long as he completed his academic responsibilities, David could talk to Lars. Lars decided that rather than convince David that he was brave, tough, and exciting or to focus on simply rewarding any on-task behavior, he would listen carefully to David’s stories and try to imagine their meaning with David. Then, Lars would join David in his imaginative play.

David told Lars of afternoon firefights with the Taliban in Afghanistan, out-swimming sharks in the Indian Ocean, jumping out of helicopters over Borneo, and raiding a den of thieves in Morocco. Lars hypothesized that David really, really needed an interested adult who had the capacity to feel with him. Lars never told David, “You must be hurting, so telling me these phony stories makes you tough,” or “You want me to know how smart you are because you know all these exotic places.” Instead, Lars allowed himself to play along with David. First thing in the morning, when David reported that he single-handedly sunk a pirate ship off the Libyan coast, Lars responded with, “Awesome, way to go Captain, I knew you could,” or “You must be exhausted. Wow! What an adventure!” Lars both authentically joined David in his play and seemed to genuinely look forward to his creative stories.

David’s adventures slowly changed. From the battles where everyone but David usually died, to racing Ferraris, summiting Mt. Everest, and piloting a hot air balloon, his tales became less murderous and death-defying. At the same time, David began playing with other children during recess. He showed classmates vulnerability when he told them he wasn’t very good at kickball. Lars saw David make friends and engage in cooperative play. David also confided in Lars some of his real insecurities, and even told classmates that he sometimes worried about his family.

As Lars worked with David the two became a team. It was clear to everyone that David looked up to Lars and the two of them had a special language. Given time, David was able to generalize his relationship with Lars to his other teacher, Rachel, and eventually to peers. By Lars engaging with David, he communicated that David was worthy. He didn’t have to lie to be special; he was special because Lars was cool and Lars liked him. David appeared happier and slowly allowed others to see the real David. When David revealed his true self, inadequacies and all, Lars and Rachel wondered if it meant that he had tamed some of the sense of shame that had ruled him.

Discussion

As of this writing, David appears far less angry and is able to complete school work independently for much of the day. He has developed age-appropriate, pro-social friendships with peers. When frustrated, he can self-advocate and calm himself down. David still relies on his powerful imagination to insulate himself from difficult feelings, but his academics are strong and he no longer screams. David’s relationship with Lars provided him with the idealization, empathy, and sense of belonging he needed to feel wanted and ultimately increase his self-esteem.

Self-esteem is the psychological strength that allows the child to feel anger without “doing” anger by behaving violently. The difference between a child having the capacity to feel a terrible feeling and do something terrible is vital. Current research suggests that self-esteem is the very construct that enables us to access our emotional worlds while at the same time empowering us to inhibit bad, aggressive, or self-destructive behaviors (Donnellan, Trzesniewski, Robins, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2015).

Most parents and teachers naturally strive to meet children’s relational needs and assist them in this development. However, because some children may not have had the experience of others meeting their needs, they may not have an internal model that allows them to readily accept a caring adult’s attempts to help them. In fact, children may go to great lengths to prevent the feared letdown of adults not meeting their needs (Ornstein, 1981). In such circumstances, it is up to the adult to creatively undertake the challenge of supporting self-esteem development and supply the tools needed to help effectively. Through educating teachers, therapists, and childcare providers on how to create close, healing connections, the Healing the Self model provides a straightforward way to raise self-esteem, reduce both anger and violence, and assist in constructing a healthier sense of self.

In Chapter 2, we explore the concept of Idealization as taught by the Healing the Self model. Establishing themselves as an admirable role model that children can idealize is the first way caring adults can create healthy, connected relationships with children who suffer with poor self-worth.