![]()

1 Asian Citrus Psyllid Life Cycle and Developmental Biology

David G. Hall*

US Department of Agriculture – Agricultural Research Service, Fort Pierce, Florida, USA (Retired)

Considerable research and review information has been published on the biology of the Asian citrus psyllid (ACP), Diaphorina citri. Hussain and Nath (1927) laid the foundation for present knowledge of ACP biology in an early comprehensive review upon which many advances have been made. Presented here are highlights of the ACP life cycle and developmental biology. ACP favors tropical/subtropical climates and hot, coastal zones (Catling, 1970; Hodkinson, 2009; Jenkins et al., 2015). Typical of all Hemiptera, ACP undergoes simple (incomplete) metamorphosis with the three typical life stages: egg, nymph and adult. Citrus is regarded as a primary host plant of the psyllid and the most important from an economic standpoint, but a number of other species within the plant family Rutaceae, subfamily Aurantioideae, are utilized by the psyllid for food and reproduction. The psyllid’s reproductive biology is closely synchronized with the production of shoots of new leaf growth (flush), as oviposition occurs exclusively on emergent leaves (often called feather flush), sometimes including young leaves associated with emergent floral shoots (Hall et al., 2008a), and young, unhardened leaves are required for the development of nymphs. While immatures of some species within the Psylloidea, including the African citrus psyllid Trioza erytreae, develop in pit-like deformations or galls induced on leaves, the Asian citrus psyllid does not and thus is free-living throughout its development on a flush shoot. However, many eggs and early instar nymphs are usually protected or hidden from view within unexpanded leaves or clusters of young leaves.

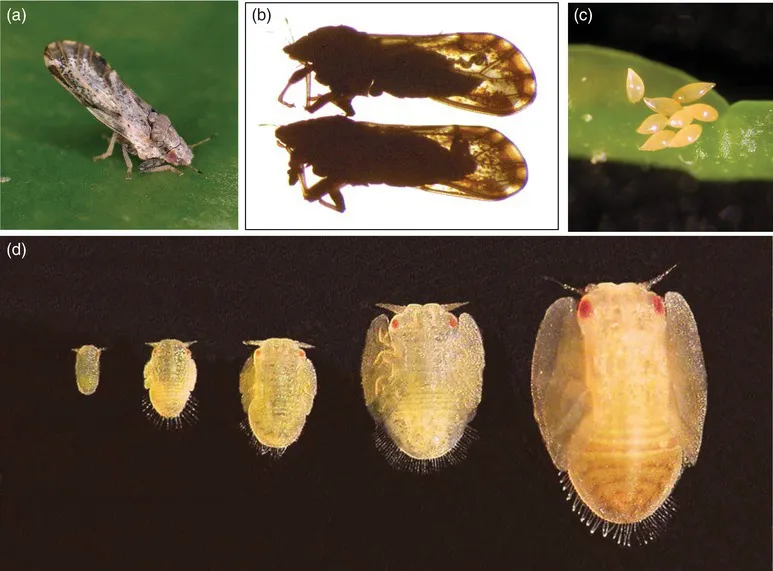

1.1 Adult Reproductive Biology, Life Characteristics and Polymorphisms

The ACP is a bisexual species, with equal numbers of females and males observed in some populations (Aubert and Quilici, 1988; Tsai and Liu, 2000; Nava et al., 2007) and a predominance of females in others (Pande, 1971; Hodkinson, 1974; Alves et al., 2014). Temporal emergence patterns of males and females are similar, with no evidence of protandry or protogyny (Wenninger and Hall, 2007; Hall and Hentz, 2016). Adults are small (2.7–3.3 mm long) with mottled brown wings (Fig. 1.1A). The end of the male’s abdomen bends upward while the end of the female’s abdomen is straight and pointed (Husain and Nath, 1927) (Fig. 1.1B). Adults rest or feed on plants with their bodies characteristically held at a ~45° angle (range 30–60°) to the plant surface. Adults feed on young stems and on leaves of all stages of development but preferentially move to newly developing flush to feed, mate and oviposit. Mating may primarily take place on flush shoots where females feed and lay eggs, but both sexes frequently walk on limbs and branches in the interior of a tree where they can sometimes be found mating. Adult males and females locate mates, in part, using substrate-borne vibrational sounds (Wenninger et al., 2009a). These sounds cannot be detected by the human ear, but individuals calling mates can be seen rapidly vibrating or beating their wings for short periods of time. Behavioral evidence indicated that females emit a sex pheromone (Wenninger et al., 2008), and recently Zanardi et al. (2018) identified acetic acid as possibly being involved. In addition, female-produced cuticular hydrocarbons may function as sex pheromones when males are in close proximity (Mann et al., 2013; Martini et al., 2014a; Moghbeli et al., 2014). During copulation, a male and female are positioned side by side with their heads facing the same direction, the male bending the tip of his abdomen down to the female. He uses his legs on the side next to the female to hold her while supporting himself on the plant surface with his legs on the other side (Hussain and Nath, 1927). Wenninger and Hall (2007) reported that copulation lasts from 20 to 100 min and occurs predominantly during daylight hours. Pande (1971) reported that mating takes place at any time during the day or night. Females maintain optimum reproductive output by mating multiple times with the same or different partners (Wenninger and Hall, 2008a).

Adults exhibit three relatively distinct abdominal colors: gray/brown, blue/green and orange/yellow (Husain and Nath, 1927; Wenninger and Hall, 2008b). Most individuals within Florida populations are blue/green, while gray/brown individuals are rarest (Hall and Hentz, 2016). Age-related shifts may occur over time in an individual’s color, but are not seasonal. The biological significance of these polymorphisms is slowly being unraveled. Husain and Nath (1927) reported that the abdomen of gravid females turns distinctively orange, particularly during spring. Wenninger and Hall (2008b) reported that abdominal color has little value as an indicator of sexual maturity and only limited value for discerning female mating status. The orange/yellow color in females reflects the presence of eggs in the abdomen; in males, it seems to derive from the color of the internal reproductive organs and this color is generally only expressed in older males. Females may associate male color with reproductive success, as they avoid blue males after previous experience (Stockton et al., 2017). Orange males mate more frequently than blue males and appear to be more sexually aggressive in mating attempts (Stockton et al., 2017). Interestingly, females that mated with orange males laid twice as many eggs as those mated to blue males (Stockton et al., 2017). There is evidence that blue/green individuals are more apt for long-distance dispersal (Martini et al., 2014b), which could be related to their larger size (Paris et al., 2016). Differences have been reported among color morphs with respect to insecticide resistance (Boina and Bloomquist, 2015). Hemocyanin may in part be responsible for the blue/green morph (Ramsey et al., 2017), but it is not known why some psyllids might produce more hemocyanin than others.

Husain and Nath (1927) reported that new adults in the Punjab region of what is now Pakistan began copulating soon after emergence and females began laying eggs on citrus soon afterwards following a pre-oviposition period of 1–3 days. In nearby Rajasthan (India), Pande (1971) reported that adults copulated 12–60 h after emergence and that oviposition commenced 8–20 h later, indicating a pre-oviposition period of 0.8–3.3 days. Wenninger and Hall (2007) reported that newly emerged adults in Florida at 26°C on orange jasmine (Murraya paniculata) mated within 2–3 days with oviposition beginning 1 day after mating for a pre-oviposition period of 3–4 days. Contrasting observations in Brazil by Alves et al. (2014) and Nava et al. (2007) indicated a pre-oviposition period of 8.5–10.9 days at 24–25°C on orange jasmine. Clearly, there are some discrepancies among pre-oviposition periods reported for ACP that may be due to environmental and host plant factors. Based on data from Yang (1989), changes in photoperiod and light intensity can influence the pre-oviposition period. Uechi and Iwanami (2012) noted that maturation of a female’s ovaries was faster when new adults fed on younger leaves.

Females lay eggs throughout their lives, provided that tender flush is available. Adult females typically lay 500–800 or more eggs over their lifetime (Husain and Nath, 1927; Tsai and Liu, 2000; Nava et al., 2007), with a reported maximum of 1378 (Tsai and Liu, 2000; a maximum of 1900 referenced by Tsai and Liu was apparently an error). The number of eggs laid by an individual female may vary depending on factors such as temperature and host plant species (Liu and Tsai, 2000; Tsai and Liu, 2000; Nava et al., 2007; Westbrook et al., 2011; Alves et al., 2014; Hall and Hentz, 2016; Hall et al., 2017a). Adult females held at 25°C were reported to lay an average of 858 eggs on grapefruit (Citrus paradisi) compared with 572, 613 and 626 on rough lemon (Citrus jambhiri), sour orange (Citrus aurantium) and orange jasmine, respectively (Tsai and Liu, 2000). Differences in oviposition rates reported on different host plant species (e.g. Tsai and Liu, 2000; Nava et al., 2007; Westbrook et al., 2011; Hall et al., 2017a) may be attributed to differences in plant volatiles, secondary plant compounds, nutritional quality and other factors but not in the abundance of simple foliar trichomes (Hall et al., 2017b). At 25°C, oviposition rates per female steadily increased over the first 10 days after mating, reaching a peak within 12–18 days, after which rates steadily declined on orange jasmine and grapefruit. In contrast, oviposition rates on lemon and sour orange peaked at about the same time but then remained somewhat steady through 60 or more days (Tsai and Liu, 2000). Nava et al. (2007) reported that females laid the majority of their eggs during the first 10 days after oviposition commenced. There can be substantial day-to-day variation among individual females in numbers of eggs laid (Husain and Nath, 1927). Such variation can be a result of mate availability, male color morph, age and possibly other biotic or abiotic factors. Based on Nava et al. (2007), differences in fecundity may also have a genetic basis.

A number of factors may influence longevity of adult ACP, including temperature, relative humidity, host plant species, food availability and reproductive status (Tsai and Liu, 2000; McFarland and Hoy, 2001; Nava et al., 2007; Hall et al., 2008b). Husain and Nath (1927) reported that adults live as long as 2 months or more, during which females may continually lay eggs. These authors reported that one adult lived for 189 days. Pande (1971) indicated that female ACP generally live longer (mean 45.0 days) than males (mean 40.5 days). Nava et al. (2007) reported that at 24°C adult males lived an average of 21–25 days and females lived an average of 31–32 days on lime (Citrus limonia), Sunki mandarin (Citrus sunki) and orange jasmine. Longevity was one of several factors that collectively suggested a greater importance of females compared with males in the epidemiology of huanglongbing (Hall, 2018). Females held at 25°C lived an average of 40–48 days on rough lemon, sour orange, grapefruit and orange jasmine (Tsai and Liu, 2000). Adult psyllids can survive without food for at least several days, depending on environmental c...