7

Gender Discrimination in the Workplace

The Help Wanted ads in a local newspaper included the following:

DANCERS

Have fun and get paid!

No experience necessary, will train.

Must be at least 18 years of age. Can earn up to $400/week to start.

Housekeepers

Now hiring FT. Exp. not necessary. Top wages! M-F, 8-5.

During the same week, the Sunday Times of India (New Delhi) carried the following ad:

Female

Office Assistant and Personal Secretary.

Willing for local travel, typing not required.

There is a striking difference in these ads. The ad for dancers was taken out by a club that features female exotic dancers, but the ad doesn’t mention gender; neither does the housekeeping ad. Everyone reading these ads is likely to expect almost all of the applicants and all of those hired (especially in response to the ad for dancers) will be women, but the ads are carefully written to be gender-neutral.

In contrast, the ad taken out in the Sunday Times of India explicitly calls for a female applicant. It is not clear exactly what the duties of this job might be (personal secretary, willing to travel with employer, but no typing required), but it is clear that only women will be considered. What does this tell us about gender discrimination in the United States versus India?

There are broad cross-cultural differences in both the type and the amount of gender discrimination practiced and accepted in the workplace. In more traditional countries, jobs might be explicitly set aside for men and for women. In most Western countries, there are relatively few formal barriers to women’s entry into a wide range of jobs and professions, but that does not necessarily mean that there is no gender discrimination. As shown in this chapter, gender discrimination can have a substantial effect on men’s and women’s work lives, even if formal barriers to the entry of men or women into particular jobs or occupations are removed. Men and women are treated differently in the workplace. Sometimes, men receive favorable treatment and women are discriminated against. Sometimes, it is the other way around. Sometimes, differences in treatment and outcomes are related to real and meaningful gender differences, and sometimes they are related to inaccurate perceptions of differences between men and women. When people are treated differently because of race, ethnicity, gender, or other similar characteristics, this is often labeled “discrimination.” This chapter examines the causes and possible consequences of gender discrimination in the workplace.

We begin by defining prejudice and discrimination and go on to discuss specific features of the workplace that may lead to or strengthen gender discrimination. A recurring theme of this section is that widely held stereotypes of women are sometimes inconsistent with stereotypes of jobs, and this lack of fit can lead directly to discriminatory actions. The second section of this chapter examines the segregation of the workforce by gender. A number of occupations are strongly sex-segregated (e.g., almost all secretaries and receptionists are women), and even within occupations, men and women often draw different job assignments. We consider economic models that attempt to explain occupational segregation and finally consider alternative explanations for differences in men’s and women’s work. We end this chapter by asking whether differences in the pay, work assignments, and career paths of men and women are in fact the result of gender discrimination, and if so, how gender discrimination might operate.

PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION

One of the most basic human tendencies is for people to favor those whom they perceive to be similar to themselves and discriminate against those they perceive to be different (Allport, 1954). This has both positive and negative effects. On the positive side, it enhances feelings of solidarity and cohesiveness in groups, families, and nations. The negative side of this basic human tendency is prejudice and discrimination.

Prejudice and discrimination are virtually universal phenomena, and people find all sorts of reasons (race, ethnicity, religion, language) to discriminate against others who differ and to discriminate in favor of those they see as similar. Discrimination on the basis of gender is not a unique phenomenon, but some aspects of the workplace are important for understanding how and why gender discrimination operates. Before looking at features of the workplace that might lead to (or work against) gender discrimination, we first define some important terms.

Defining Prejudice and Discrimination

Social psychologists (Baron & Byrne, 1994) distinguish between prejudice and discrimination. Prejudice is usually defined as an attitude toward members of a group. Most discussions of prejudice focus on negative attitudes, but clearly prejudice could cut both ways: Women might be favored in some settings (e.g., primary school education) because they are women. Nevertheless, there are good reasons to focus on negative attitudes. Prejudice against members of different groups appears to contribute to widespread segregation in the workplace and in society in general and probably fosters racism, sexism, and many of the other “isms” that are of concern to society.

Discrimination involves action toward individuals on the basis of their group membership; Baron and Byrne (1994) defined discrimination as prejudice in action. Discrimination can take a very overt form (e.g., refusal to hire women into certain jobs), but in many instances, gender discrimination involves the degree to which the workplace is open to versus resistant to the participation of women. Although many discussions of gender discrimination have focused on the ways managers and supervisors treat men and women, gender discrimination could involve managers, coworkers, subordinates, clients, or customers. In general, gender discrimination includes behaviors occurring in the workplace that limit the target person’s ability to enter, remain in, succeed in, or progress in a job and that are primarily the result of the target person’s gender. In chapters 8 and 9, we discuss the concept of a hostile work environment, especially as it relates to women’s experiences of sexual harassment. This chapter outlines some of the factors that can contribute to a hostile work environment.

There are two reasons why gender discrimination is an especially important topic. First, the likely presence of systemic discrimination on the basis of gender suggests that the number of people who might be affected is huge (i.e., discrimination against women would put half the population at a disadvantage). Given the potential impact of gender discrimination, the possibility that gender is an important influence on people’s work lives must be considered. Second, there is a good deal of evidence that men and women are treated differently in the workplace. Women receive lower wages than men, are segregated into low-level jobs, and are less likely to be promoted. As we note in sections that follow, it is sometimes difficult to determine exactly why men and women enter different jobs or receive different pay, and what appears to be gender discrimination in the workplace may in fact reflect much broader societal trends. Nevertheless, there are enough data to suggest that gender is very important in predicting a person’s occupation, pay, and progress, and that discrimination is at least a partial explanation for this disparity. Additionally, some specific features of the workplace appear to contribute to prejudice and discrimination against both men and women.

Features of the Workplace That Contribute to Gender Discrimination

Gender discrimination occurs in a number of settings. Men and women are perceived differently, are assigned different roles and are assumed to have different characteristics in most settings (e.g., around the house, cooking, cleaning, and caring for children are usually the woman’s role, whereas home repairs, mowing the lawn, and maintaining the car are the man’s role). To some extent, gender discrimination in the workplace can be thought of as a simple extension of beliefs most of us hold about the roles men and women should have in society (sex-role spillover). However, specific features of the workplace heighten the influence of gender on attitudes and actions, particularly the stereotypes assigned to men, women, and jobs, and the relative rarity of women in many work settings.

Sex-Role Spillover. The term female worker describes two roles (woman and worker) that involve different behaviors, different demands, and different assumptions. The traditional role of a woman involves caring for others, self-sacrifice, submissiveness, and social facilitation, whereas the worker role often involves technical accomplishment, competition, development and exercise of skills, and leadership. Barbara Gutek (1985, 1992) noted that beliefs about the appropriate roles for men and women are likely to “spill over” into a work setting. That is, our expectations regarding female workers will be determined in part by our expectations and beliefs regarding women in general. Even in situations where the work has little to do with stereotypically female roles, expectations about the typical roles of men and women will likely have some influence on the way we perceive and treat male and female workers. For example, in a meeting that involves several men and one woman, it is not unusual to find that both the men and the woman assume that it is the woman’s job to serve coffee, take notes, and carry out other “feminine” tasks.

You can think of sex-role spillover as a specific instance of a much more general issue, which is that everyone carries out a number of roles that may or may not be fully compatible. A female faculty member might have the roles of teacher, advisor, parent, wife, and young woman, and her interactions with others in the workplace are likely to be affected by the way she is seen in relation to each of these roles. What, then, is so special about sex roles? Why should we be more concerned with sex-role spillover than with spillover between the roles of, for example, parent and worker?

One reason for paying attention to sex-role spillover is that sex roles are both powerfully ingrained and highly salient. Unlike many other roles (e.g., teacher, parent), sex roles are just about universally applicable, and gender is usually a highly salient feature of a person. For example, if you were describing a colleague to someone else, you might fail to mention many characteristics, but you would probably not forget to mention whether you were talking about a man or a woman.

Some environments may be especially conducive to sex-role spillover. For example, work environments can become sexualized in the sense that they feature relatively high levels of sexual behavior (e.g., sexual jokes, flirting). These work environments seem to encourage people to emphasize sex roles when thinking about coworkers (Gutek, 1985), which may lead to an undue generalization of general societal expectations about men and women in the specialized setting of the workplace. Environments might also highlight gender differences (e.g., with dress codes) in ways that lead people to think of each other in terms of their sex roles rather than in terms of their roles as workers. In general, the more cues in the environment that point to a worker’s gender, the higher the likelihood that men and women will be treated differently.

Stereotypes of People and Jobs. Table 7.1 lists a number of traits that could be used to describe a person. Many of these seem to “fit” better when applied to men than to women (or vice versa). Decisiveness, confidence, ambition, and recklessness are traits we expect to find in men, whereas warmth, sensitivity, understanding, and dependence are stereotypically feminine traits. The stereotypes of some traits are so strongly sex-typed that traits viewed as positive in men (e.g., assertiveness) may be viewed as negative for women. Similarly, traits that are viewed as positive in women (e.g., sensitivity) may be viewed as negative in men.

These same words might be used to describe jobs or, more precisely, the sort of person we would expect to find in a job (e.g., decisive executive, sensitive nurse). The same adjective can be positive when applied to some jobs (e.g., aggressive sales manager) and negative when applied to others (e.g., aggressive kindergarten teacher). The same adjective can take on different connotations when paired with both a job and a person. For example, “assertive nurse” probably brings to mind a different image when the nurse is male than when the nurse is female.

TABLE 7.1 Traits That Might be Used to Describe Men, Women, or Typical Job Holders

Sidelight 7.1 Are We Closing the Wage Gap?

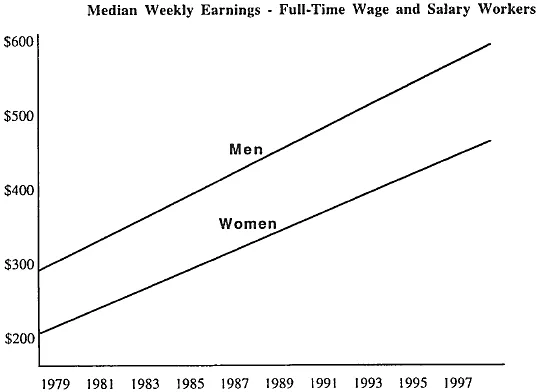

One of the most persistent concerns in discussions of gender and work is the long-standing wage gap between men and women. The U.S. Department of Labor has tracked the earnings of full-time male and female workers, as illustrated in the following figure:

In 1979, the average weekly earnings for men and women were $285 and $177, respectively. That is, at that time, women earned a bit under 62 cents for every dollar earned by men. In the first quarter of 1998, average weekly earnings for men and women were $596 and $455, respectively. That is, women earned a bit over 76 cents for every dollar earned by men. The trend over time is not quite as simple as depicted in the figure; there have been years when the gap was relatively larger or relatively smaller. However, there is still a large gap, and there is no sign that it is likely to close in the near future.

The size and nature of the wage gap depend substantially on another demographic characteristic—race. In 1983, White women earned 66.7% as much as White men, whereas in 1995, the gap had closed to 75.5%. For Black women, the gap hardly closed at all (59.7% in 1983 vs. 62.7% in 1995). For Hispanic women, there is no evidence that the wage gap is closing; in both 1983 and 1995, they earned 54% of that earned by White men.

Sidelight 7.2 What Defines “Valuable” Work?

The person who takes away your garbage is probably more highly paid than the person who teaches your children. The person who fixes your refrigerator probably makes more than the local librarian. It is not universally true, but work that is typically performed by women is usually viewed as less valuable than work typically performed by men. If you ask, “Who decides what work is valuable or important?”, the answer is likely to be “the market.” It is important to note that “the market” is shorthand for decisions made by millions of individuals in a society. The definition of what type of work is valuable and important and what type is peripheral or trivial is a value judgment that reflects widely shared cultural assumptions about the worth, centrality, and importance of different activities.

Judgments about what is valuable, good, and important in a society usually reflect the preferences, biases, experiences, and values of the groups in society that have the most power and influence. That is, judgments about what literature is worth reading (e.g., what books are regarded as classics), what sorts of art are preferred, or what sorts of houses are better naturally reflect the views of groups who have more power and influence, and the same is true in the world of work. It should come as no surprise that the activities which are most valuable and which are seen as most important in the workplace (e.g., leading others, exercising authority, controlling resources, dealing with things rather than people) are all consistent with the male stereotype, whereas activities that are seen as less valuable (e.g., dealing with children, helping others) are often consistent with the female stereotype. The workplace has historically been the domain of males, and widely accepted definitions of the types of work that are more or less valuable are value judgments that reflect the preferences, experiences, and biases of males.

Judgments about the value of different types of work are essentially subjective, and as societies change and evolve, these judgments may also change. There often is little about the work itself that determines its value (often, people’s willingness to work in a job is more important than the work itself in defining market value), and it is likely that judgments about what sorts of work are more or less valuable will change over time. Whether “women’s work” will be perceived as more valuable in the future remains to be seen.

Finally, these descriptors take on different meanings when used to describe men or women in the same job. For example, “ambitious executive” might suggest different traits when used to describe men than when used to describe women. (Stereotypes of successful female executives are often negative, focusing on the sacrifices they have made and on the outof-stereotype behavior needed to succeed in this man’s world.) Similarly, “sensitive teacher” is probably more positive when applied to females than to males. For a man, this characteristic may violate typical sex-role stereotypes and is unlikely to be viewed as an asset, whereas for women, sensitivity will probably be seen as a strength.

That jobs can often be described in terms that are strongly sex-typed has fundamental implications for understanding gender discrimination in the workplace. If you believe that men are more likely than women to possess some attribute thought to be necessary for a job, you will probably discriminate against women (and in favor of men) when evaluating applicants or incumbents in that job. For example, a person who thinks that dominance is an important part of police work will probably favor men over women as police officers (dominance is strongly sex-typed). Stereotyping of men, women, and jobs is not inevitable; people are often able to look past stereotypes and evaluate individuals strictly on their individual merits. (For a review of factors that moderate stereotyping, see Fiske & Taylor, 1991; Martell, 1996). However, there is compelling evidence that stereotypes do influence evaluations of men and women at work. The role of gender stereotypes in the evaluation of male and female managers has been studied extensively and offers a case in point.

Research suggests that women and men do not differ in management ability or motivation (Dipboye, 1987), but women are generally seen as less attractive candidates for managerial positions. Even when they have similar backgrounds and credentials, women are perceived to have fewer of the attributes associated with managerial effectiveness (Brenner, Tomkiewicz, & Schein, 1989; Heilman et al., 1989). Our stereotype of managerial success includes traits like decisiveness, confidence, and ambition, and women are usually assumed to be less decisive, less confident, and less ambitious than men. It is not clear whether this is really true or whether these traits contribute much to success as a manager, but the fact that the stereotype of a man fits the stereotype of a manager, whereas the stereotype of a woman does not, spells trouble for women attempting to enter and succeed in the managerial ranks.

A Lack of Fit. Madeline Heilman (1983) developed a “lack of fit” model to identify the conditions under which gender discrimination might be more or less likely to occur. Consistent with the preceding discussion, this model suggests that perceptions of jobs may be a critical issue in determining the extent to which gender influences work outcomes. Heilman noted that some jobs are more strongly sex-stereotyped than others. One basis for such stereotypes may be simple workforce demographics. Jobs that are mainly held by men tend to have male stereotypes, whereas jobs that are mainly held by women tend to have female stereotypes, almost independent of the content of the job. A second basis for such stereotypes is the content of the job. Jobs that include activities that are stereotypically masculine (e.g., working outdoors, working with heavy equipment) are likely to be viewed as more masculine than jobs that include stereotypically feminine activities...