What is meant by ‘private prison’? In this controversial area of penology and public administration even the terminology provides a battleground. Prison administrators tiptoe gently through the area talking about ‘contract management’ – a phrase calculated to reassure critics, as well as themselves, that these prisons are still their prisons and thus subject to the prevailing standards of public accountability. By contrast, observers who are ideologically opposed to this development emphasize the notion of ‘privatization’ – a concept already partially discredited in the western world because of its association with inflated profiteering and abandonment of the public interest. Some critics then go so far as to embrace derived terms such as ‘privateers’, redolent of piracy and pillage, to describe the private sector operators (Baldry 1994a).

Ambiguity in the contemporary use of the word ‘privatization’ has been cogently identified by Donahue (1989: 215). The first use

It is evident that some of the critics of prison privatization attack the idea as if it were being implemented in the first sense, by way of total divestiture, rather than the second sense, by way of delegated service delivery. In this regard they are perhaps marooned in the experience of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, where the notion was indeed associated with the disposal of prisoner labour to entrepreneurs and the opportunity to charge prisoners or their families for subsistence costs (Feeley 1991; Moyle 1993).

However, this simply is not the modern connotation of private prisons. Rather, at the end of the twentieth century, privatization typically refers to a process whereby the state continues to fund the full agreed costs of incarceration but the private sector is paid to provide the management services, both ‘hotel’ (including custodial) and programmatic. Variants of this include arrangements whereby the private sector also provides the physical plant itself and, more unusually, joint ventures where custodial responsibility may rest with one sector and other hotel and/or programmatic responsibilities with the other sector. Whichever of these models is adopted, however, the common denominator is that the state remains the ultimate paymaster and the opportunity for private profit is found only in the ability of the contractor to deliver the agreed services at a cost below the negotiated sum.

The problem is that, in matters of public administration, the old adage that he who pays the piper calls the tune has often been whittled away. A key question, accordingly, is whether, in remaining paymaster but delegating service delivery, the state truly does retain control over standards–whether in fact there still is present that degree of public accountability and control that must always be requisite when the state exercises its ultimate power of restraint and punishment over the citizen. To this there cannot be any a priori answer; it will always depend upon precisely how that delegation is structured and supervised. That issue – public accountability – will be the main focus of this book.

Beyond this, it is not proposed to become embroiled in terminological issues. The scope of the following analysis covers arrangements whereby adult prisoners are held in institutions which in a day-to-day sense are managed by private sector operators whose commercial objective is to make a profit from such activities. The phrase ‘private prisons’ and all related phrases refer to this.

So the book is not directly concerned with related matters such as the role of the private or the voluntary or the non-governmental organization sectors in juvenile corrections or non-institutional adult corrections, nor with private sector involvement in court escort services and the like. Of course, each of these is relevant to a full strategic understanding of prison privatization, so their experience and prospects will be invoked at appropriate points.

The threshold question, however, is whether privatization has yet attained such significance that, for all practical purposes, it is irreversible, at least in the foreseeable future. This in turn raises three subsidiary questions: how many private prisons and prisoners there are; whether these prisons are carrying their custodial weight in terms of the security needs of the total system; and whether the administrative and legal structures inhibit policy reversals by governments.

The numbers of private prisons and prisoners

Over the last decade there has been an exponential increase in the number of private prisons and the prisoners they hold. This has occurred predominantly in the western, anglophone world: the United States of America, Australia and the United Kingdom, with New Zealand irrevocably committed and some anglophone provinces of Canada flirting with the idea. Such developments as have occurred in continental Europe are tentative, described for example in the context of France and Belgium as the establishment of prisons semi-privees. In most of Europe such developments have not occurred in any form whatsoever. Intriguing questions which will be addressed in due course, therefore, are why privatization has so far been such an anglophone phenomenon and whether the orthodoxy still prevailing in Europe and the rest of the world is likely to change.

The United States

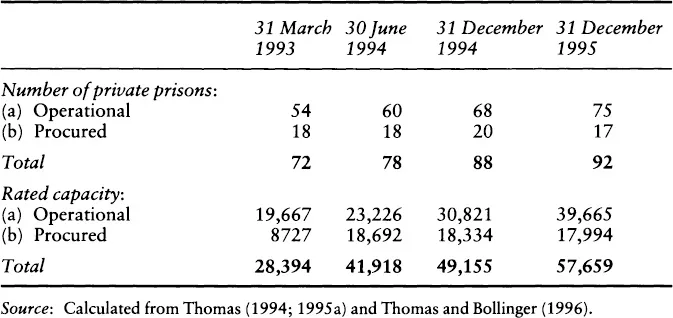

Evaluating US developments in the 18-month period ending 30 June 1994, the director of the Private Corrections Project at the University of Florida stated that the ‘alternative created by correctional privatization has moved well beyond the “interesting experiment” status it had in the mid-1980s to the “proven option” status it now enjoys’ (Thomas 1994:5). The context in which that comment was made was as follows: that in the period under review the number of prisons under contract had risen from 54 to 78; their rated capacity had doubled from 21,771 to 41,514; and the actual occupancy of operational prisons had increased from 16,101 to 23,461.

This rate of increase has subsequently been maintained. By the end of 1994 the number of contracted facilities had increased to 88, ten more in a mere six months. Rated capacity was almost 50,000, whilst actual occupancy had increased to nearly 29,000. Private prisons were coming on-stream at regular intervals.

Throughout 1995 and 1996, this momentum has continued. Virginia, a newcomer to this area, committed itself to four private prisons with a rated capacity of 3800; New Mexico positioned itself by legislative committee hearings to embark upon an increased level of private sector participation; Florida let three more contracts and increased the capacity of existing institutions by 50 per cent; both Tennessee and Texas contracted to add further capacity to already contracted prisons; Alaska, which hitherto had sent some of its prisoners to a Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) facility in Arizona, investigated the possibility of establishing a private prison on its own territory; and, perhaps most significantly of all, the federal government announced that for budgetary reasons the majority of new minimum- and low-security jails and prisons which it henceforth builds will be privately managed. The significance of this lies in the fact that the Federal Bureau of Prisons had traditionally been regarded as something of a standard-bearer in American corrections and, as such, had been resistant to private sector involvement.1 The pace of recent increase and the position as at 31 December 1995 can be seen in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Private prison developments in the USA from 31 March 1993 to 31 December 1995

In personal conversation a senior executive of CCA – widely regarded as the market leader – had in September 1995 told the present author that he believed the USA market would expand ‘almost indefinitely’. This vibrant confidence had been reflected in the tone of CCA’s 1994 annual report to shareholders: ‘There are powerful market forces driving our industry, and its potential has barely been touched.’ From the other side of the fence, the executive director of the Florida Correctional Privatization Commission – the body charged in that state with the function of allocating contracts to the private sector – also expressed in personal conversation his view that privatization is now irrevocably part of the correctional scene.

Support for these views is found in Thomas’s estimate (1996:20) that by the end of 1996 there will be approximately 115 operational or commissioned US private prisons with rated capacity totalling about 75,000 – an accelerating pace of expansion in the passage of only a single year. Of course, even if every one of these facilities were operational, their total number of inmates would still only amount to about 4.6 per cent of the massive US incarcerated population. However, an alternative perspective is that if all of those private prisons were to be closed, US correctional authorities would have to find extra accommodation equivalent to the combined prison populations, of, say, Japan and Malaysia or, alternatively, Australia and South Korea.

In that context, the probability must be that private prisons in the USA are here to stay for the foreseeable future. Indeed, the numbers could well double again in the next five years. Thomas is right: privatization is now a proven option.

Australia

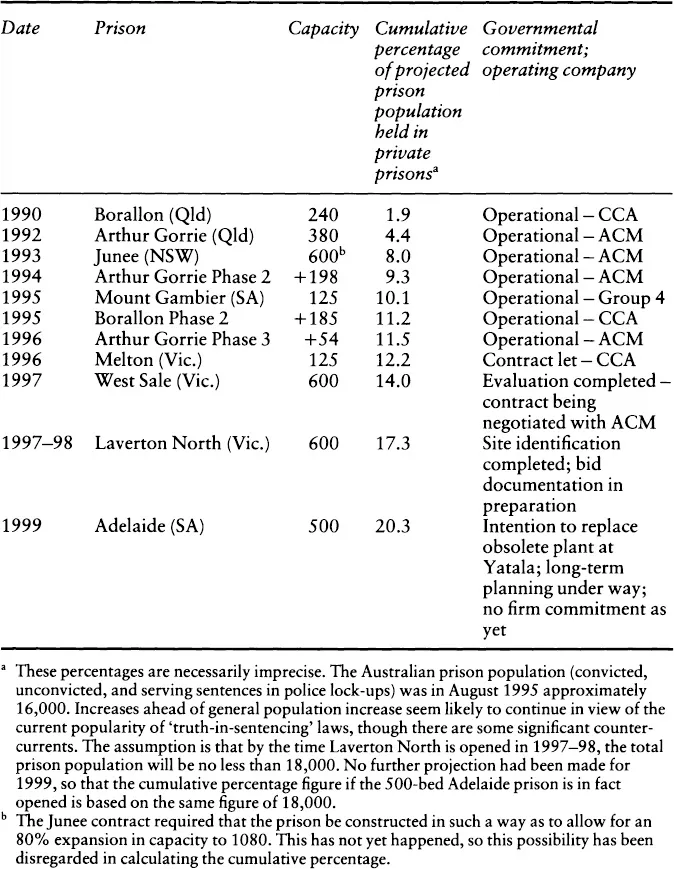

Australia was the second westernized anglophone country to commission and open a private prison. In January 1990 a 240-bed medium-security institution for convicted offenders was opened at Borallon, in Queensland. The contractors are Corrections Corporation of Australia, which is a consortium led by CCA of the United States.

Two other private prisons quickly followed: the Arthur Gorrie Correctional Centre in Queensland and Junee prison in New South Wales. Australasian Correctional Management (ACM) was the successful bidder in each case. ACM is a subsidiary of Australasian Correctional Services, which is a consortium headed by the Wackenhut Corrections Corporation (the second largest player in the USA market).

Table 1.2 (page 6) summarizes the growth of private prisons in Australia. It can be seen that about 20 per cent of the projected Australian prison population could be held in a total of eight private prisons by the end of the twentieth century. This would constitute the highest percentage in any country in the world.

Bearing in mind the threshold question as to whether these arrangements could be unscrambled, it should be emphasized that this high percentage which will ultimately be held in private prisons amounts to only 3600 prisoners – a drop in the bucket by USA standards, though the equivalent of the total prison population of a mid-level state system in Australia as at the year 2000. It is also relevant that one of the four state jurisdictions involved – New South Wales, the largest – only has one private prison and there is known to be some distaste for this development at both political and managerial levels, so that privatization might conceivably be unscrambled there. If so, the counter-balance is that each of the other three jurisdictions not currently committed to privatization has actively considered it already (Harding 1992) and seems to have put a decision on hold rather than rejected the possibility for all time.

On balance, it is unlikely that there will be exponential increase in private prisons and prisoners comparable to that which may occur in the USA. This is primarily because there is unlikely to be the massive overall increase in prisoner populations that has characterized US experience. For all that, private prisons in Australia can at this stage fairly be said to be a proven option, integral to the total system.

The United Kingdom

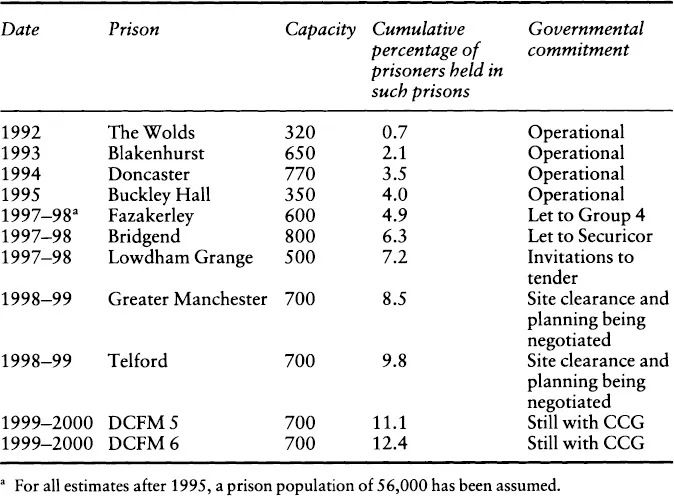

The UK2 followed Australia into the privatization field in May 1992 with the opening of The Wolds prison in Yorkshire. The management of this 320-bed remand prison was contracted to Group 4/Securitas, an Anglo-Swedish consortium working in the general security field in Europe and globally. Other private prisons were soon opened: Blakenhurst (650 beds), Doncaster (770 beds) and Buckley Hall (350 beds). During 1995 contracts were also let for Fazakerley, near Liverpool (600 beds) and Bridgend, Mid Glamorgan (800 beds); these two prisons are scheduled to become operational in late 1997.

Table 1.2 Private prison developments in Australia, 1990–99

Table 1.3 Private prison developments in England and Wales, 1992–2000

Subsequently, because of urgent accommodation needs in the East Midlands area, another prison (Lowdham Grange) was fast-tracked into the private sector programme. This will accommodate 500 medium-security male prisoners, and it is intended to expedite its development so that it should open at about the same time as Fazakerley and Bridgend. At that time there will be about 4000 private prison beds distributed through seven prisons, housing about 7.2 per cent of the total prison population.

The British government had also announced that it was committed to commissioning at least four more private prisons, with a total capacity of about 2800 beds. The first two of these contracts have reached the site planning and specific needs evaluation stage; the other two are still at the most preliminary stage. Once these are all operational, however, the number of prisoners held in 11 private prisons will total 6800 or about one-eighth of the total projected prison population.3 The committed privatization programme is summarized in Table 1.3.

A wild card is the outcome of the next general election. The Labour Party is on the record as promising that all private prisons will be returned to the public sector when the present contracts expire:

The privatization of the prison service is morally repugnant… It must be the direct responsibility of the state to look after those the courts decide it is in society’s interests to imprison. It is not appropriate for people to profit out of incarceration.

(Jack Straw, The Guardian, 8 March 1995)

The priority, in Labour’s view, is to implement the reforms recommended by the Woolf Inquiry (Woolf and Tumim 1991), and their fear is that privatization would cut across this primary objective.

On the other hand, the present government seems committed to further privatization. The original policy announcement of 1993 which provided the foundation for Fazakerley, Bridgend and the four additional contracts spoke of ‘about 10%’ of the UK’s 134 establishments being privatized (ministerial statement, 2 September 1993). Subsequently, the home secretary spoke of the need to renovate and refurbish 25 of those 134 prisons and of the possibility of inviting the private sector to participate in this capital-intensive project in return for long-term management contracts (The Independent, 16 August 1995).4

Which of these competing sc...