![]()

Chapter 1

Job Analysis and Benchmarks

JOB ANALYSIS IS ESSENTIAL TO FULFILL MANY ORGANIZATIONAL OBJECTIVES

Human resource management is currently the stylish label attached to what has formerly been known as “personnel” or “personnel operations.” What it refers to is an organization’s activities, among others, to select, hire, appraise performance, pay, promote, and transfer workers.

These activities have two primary purposes. The organization wants to secure an efficient and effective (productive) workforce—the best it can get for what it wants to spend, and it wants to deal with its workforce in a fair and equitable manner for both morale and legal reasons. What is good for morale is believed to contribute to being productive. And certainly staying within the law is a good way to keep out of trouble. All of these activities and their worthy objectives involve a lot of technical work, the underpinning for all of them being objective, detailed descriptions about the work that needs to get done. Obtaining the information for these descriptions is job analysis.

This volume deals with a method of job analysis especially designed to obtain and communicate information about jobs. Specifically, we describe the procedures involved in developing information about job tasks, evaluating their relevance to job performance, and utilizing this information in job evaluation.

LANGUAGE: A FUNDAMENTAL PROBLEM IN JOB ANALYSIS

Gathering job analysis information that is detailed, objective, reliable, and valid (these are the holy cows of the art and science of industrial psychology) might seem to be simple, but it is not. Regardless of the method used to convey job analysis information, it is still descriptive information conveyed by means of language. Verbs are used to denote actions; nouns to denote material, products, subject matter, and services, as well as machines, tools, equipment, and work aids. Sometimes adverbs and adjectives slip in to emphasize one or another action, material, or tool to indicate standards or to suggest degrees of efficiency and effectiveness.

Left to their own devices, respondents, whether incumbents or analysts, introduce subjective elements into the descriptive material. They have a world of words to choose from, and one observer’s choice may not be that of another. This calls the reliability and validity of the observations into question. It is inherently very difficult to choose words that reflect the relative differences in complexity among the work requirements of various jobs. Yet this is what needs to be done if the objectives of fairness and equality are to be realized in carrying out the activities previously listed. Because we are dealing with words that have a strong subjective element, human resource personnel are driven to make assumptions and inferences that weaken the validity of the data. Functional Job Analysis (FJA) has been designed to deal directly with this problem and thus produce more objective descriptive data. How it does this is described in what follows. Benchmarks are the capstone of this effort.

FJA CONTROLS THE LANGUAGE OF JOB ANALYSIS

The main thrust of FJA is to tackle the language of job description and to control its use so various observers can produce data about jobs all can agree on. The following are some of the ways in which FJA controls the use of language:

• FJA uses the natural dimensionality inherent in the English language as a point of departure. All this means is that by studying how words have been commonly used descriptively one finds some words have been naturally clustered to express a hierarchy of complexity or skill, for example, feed, tend, operate, and setup machines imply a successively greater degree of involvement and hence skill on the part of the worker.

• FJA draws a sharp distinction between the verbs used to describe what workers do and what gets done. For example, a verb such as welding tells what is getting done. It can be done by a worker “operating” a machine or “manipulating” welding tools. Similarly, a verb such as reporting tells what is being accomplished, but it is important to distinguish whether the worker is “compiling” data for the report, “analyzing” the data for optional interpretations, or “coordinating” the data to make recommendations. These different ways of functioning with regard to an output can have important implications for personnel operations.

• FJA recognizes that the objects of worker behaviors can be Things, Data, or People and there needs to be a coherence, a matching, between the action verbs used and the results of those actions. For example, verbs associated with Thing actions need to have Thing outputs.

• FJA insists that describing the work that gets done and what workers do needs to avoid the use of qualifying adjectives and adverbs. Adverbs and adjectives need to be restricted to describe performance standards.

• FJA uses a basic English sentence to describe tasks. A task performed by a worker must include an action verb and an indication of the object of the action (Thing, Data, or People); using what Tools, Machines, Equipment, or Work Aids; drawing on what knowledge and instructions; relying on what skills and abilities; in order to achieve/produce what.

These considerations and specific limitations serve as controls in the use of language to describe work and serve to clarify the language of description and the elements linking job requirements and worker qualifications.

THE ROLE OF FJA SCALES

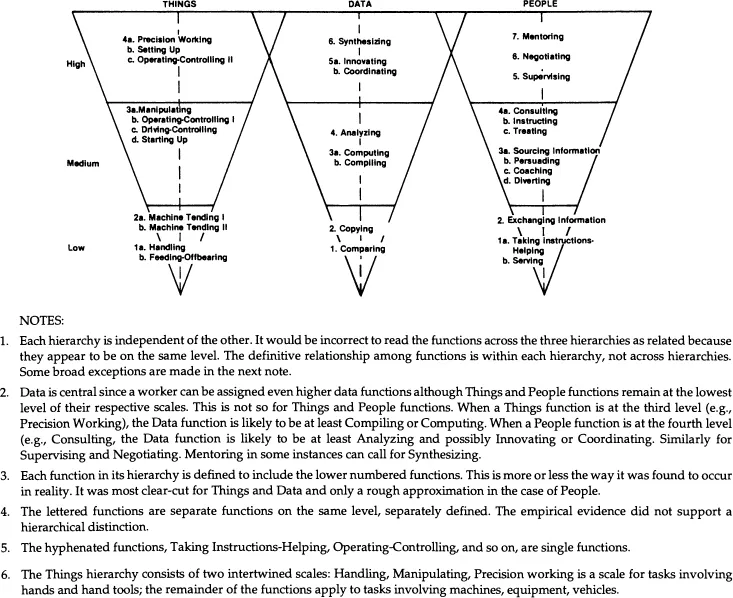

The language controls are made possible through the use of seven scales, each of which is a channel for the language customarily used to describe what workers do in jobs. For example, workers physically relate to things, mentally relate to data, interpersonally relate to people. Three scales take the behavioral terms used to express these relationships, define them, and organize them from lowest to highest complexity as shown in Fig. 1.1.

These scales plus four others are ordinal, meaning the levels of the scales go from low to high with the higher including the lower levels. They are used to evaluate and rate the specific descriptive material of jobs and produce comparative ratings on each of 10 components—three for levels of difficulty and three for orientation to Things, Data, and People—and four for levels of Worker Instructions, Reasoning, Math, and Language (see Appendix A).

The result is a conceptual framework that anyone, but especially the job analyst, can consult to understand and establish the level of complexity that may be associated with a task. An effect of language control is to generate a terminology for “what workers do” and a terminology for “what gets done,” thus resulting in a more sharply focused picture of a job-worker situation, the place where behavior and technology interact.

FIG. 1.1. Summary chart of worker function scales.

An analyst needs these reference points because embedded in the language of description are the analyst’s perceptions of the difficulty/complexity levels of the work being performed. These perceptions may be based on what an incumbent or supervisor tells the analyst and/or what the analyst judges from personal experience. By consulting the scales, the analyst can determine the levels attached to the behaviors implicit in the language used to describe the job.

The Things, Data, and People functional scales define functional/behavioral levels that are, in effect, skill levels. The Worker Instructions scale defines the mix of levels of prescription and discretion the job requires. The Reasoning, Math, and Language scales define the general educational development levels required to do the work. Thus, a job analyst is provided with reference points to evaluate the language he or she uses to describe a job and to determine whether the complexity levels implicit in that language are the ones intended.

THE ROLE OF BENCHMARKS

Experience has shown that the definitions of scale levels, although helpful, are not enough of a guideline, the vagaries of language being what they are. Practitioners want benchmarks, which are simply examples from jobs that have been rated at various levels of the aforementioned scales. Actually, when raters do their work, they generate personal benchmarks to achieve consistency, drawing on their personal experience and memory. However, the rating process can be better served by having common benchmarks that all raters can refer to as needed. The benchmarks in this volume are intended to serve this need.

Benchmarks are more concrete than generalized definitions of levels, which border on the abstract. An example of both a generalized definition of a level from the FJA scale for Data—Analyzing—and two benchmarks that illustrate it demonstrates the difference and the value of both:

Analyzing: At this level, the individual examines and evaluates data (about things, data, or people) with reference to the criteria, standards, and/or requirements of a particular discipline, art, technique, or craft to determine interaction effects (consequences) and to consider alternatives.

Task 1: Review/evaluate resumes and/or applications received for a current job opening and prepare a summary report of qualifications of applicants, drawing on knowledge of job requirements and allowable equivalencies and relying on writing, analytical, and computer skills in order to determine which applicants meet the minimum requirements of the position and can be sent to the hiring supervisor for review.

Task 2: Consider/evaluate work instructions, site, and climatic conditions, nature of load, capacity of equipment, other crafts engaged in the vicinity, drawing on work order and experience and relying on analytical skill in order to situate (spot) crane to best advantage.

These two benchmark tasks not only manifest the worker action language for analyzing but also the knowledge, skill, and ability (KSA) supporting the behavior.

Benchmarks are tasks taken from FJA task banks. A task bank, an example of which can be found in Appendix C, is an inventory of the tasks that incumbents in a particular job have indicated they perform to turn out the outputs that they were hired to produce. The tasks are stated in the words of the incumbents.

Why tasks and not jobs for benchmarks? As is described in chapter 3, the simple reason is that jobs are much too vague an entity on which to hang an objective value. Tasks are much more stable units of work. In fact, quite a range of scale values can apply to the various tasks of a job.

ADDING BENCHMARKS

Ultimately, users will want to develop their own benchmarks using tasks drawn from job analyses and consensus ratings carried out in their own organization. Information on ordering a computer disk from the publisher is available at the end of the Preface of this book so that human resource specialists can more easily compare tasks from a variety of jobs in their organization with those included here. In this way the tasks will be constantly available for review and amendment if necessary. The authors hope this activity will inspire human resource specialists in these organizations to communicate with them. Constant updating of experience in using the benchmarks may thereby result in revision where necessary. Comparing the benchmarks against the level definitions of the scales may result in improvements of these definitions as well. As is evident, none of this material should be regarded as written in stone.

SUMMARY

Organizations, to achieve the essential objectives of fairness and equality in their human resource management activities, must do so on the basis of objective, reliable, and valid information about their job requirements. To obtain such information they carry out job analyses. The job analyses present serious problems mostly having to do with the language in which they are written. FJA is a method of job analysis that advocates the use of language in a specific and precise manner and makes use of scales as a referent framework within which to comprehend the job information collected. It is in this sense that the language of job description is controlled. Defining scale levels for functional skills, worker instructions, reasoning, math, and language has proven to be quite helpful. However, practitioners have expressed a need for benchmarks both to facilitate the use of the scales and to increase the reliability and validity of the data.

OUTLINE OF THIS BOOK

Chapter 2, “Background and Overview,” provides a brief historical review of the 45-year history of FJA, as well as a contemporary context for the importance of job analysis. It also briefly describes current FJA practice in producing a job analysis database.

Chapter 3, “Communicating Job Information,” discusses in detail the problems of communicating about work, including the subtle differences involved in the choice of words. It also explores the reason for focusing on tasks rather than jobs and the crucial role of level and orientation measures (Worker Function scales) in defining a task.

Chapter 4, “Enabling Factors: Scales of Worker Instructions and General Educational Development,” provides a detailed description of the scales and their role in enabling behavior. These scales help define the KSAs involved in tasks. It also includes a discussion of the meaning of experience.

Chapter 5, “The Structure of an FJA Task Statement,” describes how a standard English sentence is used as a framework for systematically incorporating all the essential information needed for human resource management including the enablers, knowledge, and instructions.

Chapter 6, “Writing Task Statements: Style Guidelines,” explores the practical procedures and the pitfalls to be avoided when constructing task statements using FJA concepts.

Chapter 7, “Generating Benchmarks,” describes the methods used to develop the benchmark ta...