Performance practice and audience modes of reception and interaction vary markedly among different musical genres, cultures and sub-cultures. Pitts notes that “the traditional practices of the Western concert hall assume a relatively passive role for listeners” (Pitts, 2005, pp. 257–269), which contrasts with Williams-Jones assertion that “audience involvement and participation is vitally important in the total gospel experience”(Williams-Jones, 1975, p. 383). A typology of audience/performer relationships can therefore be divided into a dichotomy between participatory and non- participatory interactions.

Audience participation is not an uncommon element in many different fields of creative practice. Tony and Tina’s Wedding was an immersive theatre piece from 1985 that ran for over 20 years in New York and was performed in more than 150 cities (Cassaro and Nassar, 1985).The audience played the part of the wedding guests and mingled with the characters as they ate, drank and danced. The Rocky Horror Picture Show film has inspired audiences to dress up as the characters, recite the script and sing along with the movie (O’Brien, 1975). There have been a variety of interactive film formats including CtrlMovie that give the audience a way of steering the narrative via real-time engagement and narrative decision-making through the medium of an app (CtrlMovie, 2017). Performance artist Marina Abramović has interacted with an audience on many occasions and in a variety of contexts. She says:

Performance is mental and physical construction that performer make in a specific time and a space in front of audience and then energy dialogue happen. The audience and the performer make the piece together.

(Abromavić, 2015)

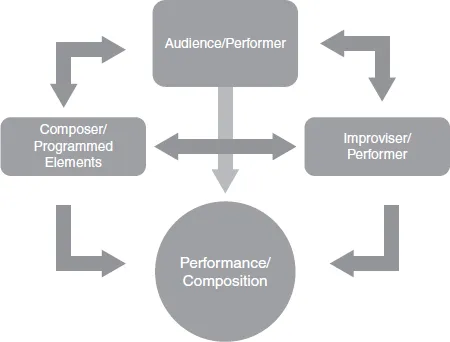

Small proposes that “Music is not a thing at all, but an activity, something that people do” (Small, 1998, p. 2). Small describes this activity as musicking, which he defines as the set of relationships in the performance location between all of the stakeholders. For Small the protagonists in the performance include a cast of characters from everyone involved in the conception and production of sound to the venue management, cleaner, ice cream vendor and ticket seller. His proposal that music is an activity is at the center of this research, but it is being extended and reworked on his premise, taking the participatory element and turning it into an active musical involvement, thus trying to create a more democratic relationship between performer and audience. Nyman expands on this idea: “experimental music emphasizes an unprecedented fluidity of composer/performer/listener roles, as it breaks away from the standard sender/carrier/receiver information structure of other forms of Western music” (Nyman, 1999, pp. 23–24). Nyman is focused on the works of experimental composers, including John Cage, for whom the audience is expected to play an active role but only as an engaged spectator.

Nyman quotes Cage: “we must arrange our music, we must arrange our art, we must arrange everything. I believe, so that people realize that they themselves are doing it, and not that something is being done to them” (Nyman, 1999, pp. 23–24). Cage seems to be staking a claim here for the audience as participant in the creative process, but Cage does not propose any kind of active audience involvement beyond an immersive engagement with the performance or as an involuntary sound source, as in his composition 4′33″.

In his taxonomy of research and artistic practice in the field of Interactive Musical Participation, Freeman creates three ranks of interactions (Freeman, 2005b, pp. 757–760). The first covers compositions in which the audience has a directly performative role, generating gestures that either form the whole of the soundscape or are integrated into the overall sonic and compositional architecture of the performance. The second category turns the audience into sound transmitters of pre-composed or curated sonic material through the medium of ubiquitous personal hand-held digital computing devices such as mobile phones. Freeman’s final category sees the audience as influencers; this process can involve interactions as diverse as voting via hand-held digital devices and waving light sticks in the air. The data from these inputs is then analyzed and presented to the performers as some kind of visual cue that triggers a predetermined sonic gesture.

Of the three ranks identified in the taxonomy of audience interaction, it is the one that functions as a container for artifacts that gives the audience the potential for performing which is the most heterogeneous. The audience’s affordances within the performance environment range from the realization of pre-composed material to the interpretation of abstract instructions and the triggering of samples. The Fluxus composer Tomas Schmit’s composition Sanitas no.35 has a performance script or score that reads as follows (Schmit, 1962):

Empty sheets of paper are distributed to the audience. Afterwards the piece continues at least five minutes longer.

These instructions are in tune with some of the principles laid out in the FLUXMANIFESTO ON ART AMUSEMENT by George Maciunas, the founder and central co-ordinator of Fluxus, in 1965 (Maciunas, 1965). Maciunas says:

He (the artist) must demonstrate self-sufficiency of the audience, He must demonstrate that anything can substitute art and anyone can do it.

Berghaus views the type of instructional compositional device proposed by Fluxus artists as an opportunity to unlock the creative potential of the audience (Berghaus and Schmit, 1994).

A more obviously active role for the audience is conceived in the 1968 recipe/performance instructions for Thoughts on Soup, a performance piece devised by Musica Elettronica Viva (MEV) (Rzewski and Verken, 1969). MEV was a composer’s cooperative set up in 1966 in Rome by Allan Bryant, Alvin Curran, Jon Phetteplace and Frederic Rzewski for the performance of new compositions using live electronics. By 1969 the group had integrated both acoustic and found sound sources into their practice, and with Thoughts on Soup Rzewski calls for ‘listener-spectators’ to be gradually blended in with ‘player-friends’ (Rzewski and Verken, 1969, pp. 79–97). Rzewski says:

In 1968, after having liberated the “performance”, MEV set out to liberate the “audience”. If the composer had become one with the player, the player had to become with the listener. We are all “musicians”. We are all creators.

The recipe/performance instruction for Rzewski’s Thoughts on Soup specifies a mix of traditional instruments and instrumentalists combining with novelty instruments (duck call, police whistle, pots and pans) for the ‘listener-spectators’ as well as microphones, amplifiers, mixers and speakers.

In the Sound Pool (1969), which Rzewski describes as “a form in which all the rules are abandoned”, the audience is asked to bring along their own instruments and to perform with the MEV. In the context of Sound Pool, musicians are no longer elevated to the position of a star but instead work with the audience managing energies and enabling the audience to “experience the miracle” without overwhelming the audience-performers with their virtuosity. The outcome of this process is that the audience no longer exists as a discrete entity (Rzewski and Verken, 1969, pp. 79–97).

Rzewski’s negation of the audience as an alterity creates an opportunity for the collaborative emergences of creativity characteristic of the processes of group improvisation (Sawyer, 2003, pp. 28–73). It is Rzewski’s reshaping of the role of the audience that this research will seek to explore using digital technologies and modular compositional building blocks.

In Jean Hasse’s composition Moths (1986), the audience become performers and are asked to whistle a variety of pitches and rhythms from a graphic score as directed by a conductor. The mass of overlapping pitches create an eerie soundscape. The score’s instructions call for several minutes of rehearsal followed by three minutes of performance. Hasse reflects upon her creative process:

Continuing a deconstructionist line of thinking, in 1986, while living in Boston, I had a chance to broaden my compositional scope away from that of a “conventional” performer, through the simple device of bringing an audience into the performance. During a concert interval years before, I had been intrigued to hear people whistling casually in the hall and wondered what it would sound like if this were formalized and even more people whistled in synchrony. My earliest sketches involved passing out whistling instructions to selected members of the audience, something akin to a Yoko Ono conceptual event. In Boston, however, when a concert appearance allowed me to develop the idea, the result became a graphic score for an entire audience to perform.

(Hasse, 2017)

Hasse’s 2001 piece Pebbling follows a similar model, with the audience clicking and rubbing together pebbles on cues from a conductor. Comparing the composition to Moths, Hasse comments that “it has a relatively similar graphic score, and was conducted, by gestures, to the gathered crowd. They produced a ‘chattering’ percussion piece, amplified by flutter echo effects arising from the cliffs—an interesting extra dimension”. Hasse concludes “Ideally, audience involvement should feel somewhat natural … and necessary, in a variety of performance contexts ” (Hasse, 2017). Hasse’s analysis that audience involvement should be “natural … and necessary” runs counter to some of the examples of compositions within this literature review, which focus more on process and research rather than musical outcomes.

The Eos Orchestra at a fundraising banquet for the orchestra performed Terry Riley’s In C in 2003, as detailed in Bianciardi et al. (Bianciardi et al., 2003, pp. 13–17). Pods were set up on each of the 30 banqueting tables that the audience would touch on a cue from the cond...