![]()

PART I

The consequences of gender stereotypes

![]()

1

SEXISM AND THE GENDERING OF PROFESSIONAL ASPIRATIONS

Lavinia Gianettoni and Edith Guilley

Introduction

Despite political incentives for the diversification of girl’s professional aspirations and career choices, taking a course predominantly followed by the opposite sex remains a relatively minor phenomenon in Switzerland (Grossenbacher, 2006, Gianettoni, Simon-Vermot and Gauthier, 2010), as in other European countries (see for example Baudelot and Establet, 2001; Francis, 1996; Lightbody and Durndell, 1996).

This “sexual division of professional orientation” (Vouillot, 2007) is at the heart of the construction of gender inequalities because it lays the foundations for horizontal and vertical segregation of the labour market. The horizontal segregation refers to the fact that many occupations are strongly gendered (i.e. occupied by a clear majority of men, like in technical occupations, or of women, like in caring occupations). The vertical segregation refers to the fact that men are very often at the top of occupational hierarchies (directors, etc.) while women are very often subordinate (Farmer, 1997). These segregations illustrate well the principles of division and hierarchy of the sexes that structure the gender system (Delphy, 2001). The principle of division corresponds to the widespread idea that there are “men’s occupations” and “women’s occupations”. The principle of hierarchy corresponds to the idea that “a man’s work is worth more than a woman’s work”. It is reflected in the lower salaries associated with highly feminized occupations (Olsen & Walby, 2004; England, Allison, & Wu, 2007) and in the clear underrepresentation of women in senior executive or equivalent positions (e.g. university professors; Farmer, 1997). To summarize, women are concentrated in certain areas of competence and cannot easily reach the most prestigious and best remunerated positions. This has obvious repercussions for the career possibilities open to women, and especially to women living in a heterosexual couple with children: They are more likely to reduce their occupational activity once they have children (Vondracek, Lerner, & Schulenberg, 1986), for reasons that are both ideological (“it’s a mother’s job to look after the children”) and institutional (because women generally earn less than their partners). This withdrawal from the labour market, even if only partially, damages their subsequent chances of pursuing a career. Already in adolescence, young girls anticipate their future roles and make a “choice of compromise” for less prestigious occupations that will facilitate the reconciliation between their career and their private life (Duru-Bellat, 2004).

Studying current professional aspirations of young people aged 13–15 years old is important in a life-course perspective since they correlate to subsequent careers once these youngsters reach adulthood. Indeed, occupational aspirations of adolescents are formed with a relatively realistic assessment of future opportunities and difficulties in realizing personal goals (Gottfredson, 1981). They are predictive of subsequent career choices since ambitious occupational plans were shown to be good predictors of high status attainment in early adulthood (Cochran, Wang, Stevenson, Johnson, & Crews, 2011; Sikora & Saha, 2011). This is the case even after youth educational plans and performance are all taken into account.

Professional aspirations: impact of sexist ideologies and family context

Several studies have shown that family structure has an influence on the gendering of young people’s aspirations (for an overview see Guichard-Claudic et al., 2008). In particular, girls who have grown up in a family in which the mother’s occupational status is equal to or higher than that of her partner choose professional sectors in a less gender-stereotyped way. But in terms of adolescents’ professional aspirations, much of the research has focused on parental support and parental expectations (for a review, see Whiston & Keller, 2004). While the influence of the family structure or support is relatively well documented, few studies have explicitly addressed the impact of adherence to sexist ideologies by young people and their parents on the gendering of professional aspirations. To our knowledge, only one recent study showed that the internalization of gender stereotypes by young people (i.e. the use of gender stereotypes to define self-competence) predicted their career intentions (Plante, de la Sablonnière, Aronson, & Théorêt, 2013).

What we know from our own research (Gianettoni et al., 2010; Gauthier & Gianettoni, 2013) is that young adults who express a strong adhesion to traditional gender roles tend to have gender-typical occupations. Indeed, we showed that women who at age 23 occupy very gender-conforming occupational positions give more importance to their family compared to their career. By contrast, women who occupy atypical positions do not relegate their career to the background. We deduced from these findings that occupational activities that are gender-typical reinforce the two basic postulates underlying the gender system (division and hierarchy). In those studies we did not, however, test to what extent gender-typical aspirations are underpinned by a more or less strong adherence to the ideologies that legitimate the gender system. This was because in those studies, based on secondary analyses of TREE data (Transition from Education to Employment, TREE 2013), we did not have measurements of the perceived legitimacy of the gender system (i.e. measurement of sexism).

To fill this gap, the study described in the present chapter explored the role played by sexist ideologies in the gendering of young people’s aspirations. To this end, we used the old-fashioned and modern sexism scales developed by Janet Swim and colleagues (Swim, Aikin, Hall, & Hunter, 1995). This scale distinguishes a form of explicit sexism called “old-fashioned sexism” from a more subtle form, called “modern sexism.” Old-fashioned sexism refers to gendered stereotypes according to which women are less competent and women and men should expect to be treated differently. Modern sexism is characterized by non-recognition of the sexist discrimination that persists in our society, hostility towards demands for equality of opportunity, and a lack of support for policies designed to promote gender equality (for example, in education or work). Our hypothesis is that, for girls, atypical professional aspirations require not only a degree of self-confidence on their part (see Gauthier & Gianettoni, 2013; Lemarchant, 2008) but also a distancing from the norms of the gender system. We, therefore, hypothesize that modern and old-fashioned sexism, and legitimate gendered roles and gender system, have to be rejected by girls in order for them to be able to aspire to occupations mainly occupied by men (further named as “masculine” occupations). For the boys, we put forward a comparable hypothesis: atypical aspirations on their part also imply a distancing from the socially valued masculine norms, and thus we expect the rejection of sexism again to be a necessary condition for their gender-atypical professional aspirations.

Concerning the link between parent’s ideologies and youth aspirations, some authors explore the influence of parent’s sexist ideologies on their children’s ideologies (Eccles, Jacobs and Harold, 2010), or on children’s interests (Barak, Feldman and Noy, 1991). To our knowledge, no study has explicitly analysed the impact of parent ideologies on child occupational aspirations. We nevertheless hypothesize that parents’ degree of sexism will have an influence on their children’s professional aspirations: the more sexist the ideological context where young people are socialized, the more they will aspire to gender-typical occupations.

Our survey

Our survey was financed by the National Research Program (NRP 60) “Gender Equality” of the Swiss National Science Foundation. For a detailed overview of this study, see Guilley et al. 2014. We questioned 3,179 pupils at or approaching the end of their compulsory schooling in various schools in five Swiss cantons, as well as their parents. The selection of cantons and schools for the survey was made with a view to best fulfilling the principle of representativeness (urban/rural areas, richer/poorer neighbourhoods, linguistic regions). Regrettably, almost all the German-speaking cantons declined to take part in the survey, with the exception of Aargau. Our sample is, therefore, not representative as regards the linguistic regions. The cantons where schools agreed to take part in the survey are Geneva, the French-speaking part of Bern, Vaud, Ticino and Aargau. The pupils and their parents completed a standardized questionnaire on various dimensions relating to professional aspirations and on their adherence to sexism.

Sample

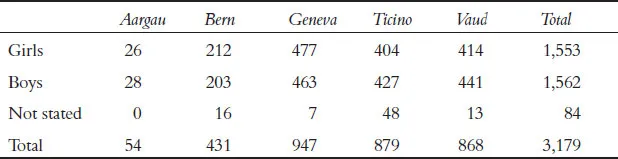

Pupils

The young people who took part in the survey were pupils of 20 schools spread over the five selected cantons. They were aged 13 to 15 when they completed the questionnaire (in 2011) and were enrolled in the lower secondary school (i.e. grades 9, 10 and 11). They were thus at a time in their lives when the choice of their future professional training had to be made. The pupils completed the questionnaire on computers in the classroom (in all the French- and German-speaking cantons), or on paper in the classroom (as required by the canton of Ticino). Their distribution by canton of residence and sex is shown in Table 1.1.

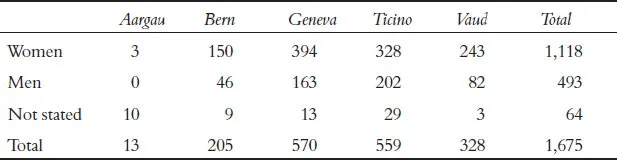

Parents

The parents were invited to take part on the basis of their children’s participation. A single (paper) copy of the questionnaire was sent to them and could be answered by either parent. In no cases were two questionnaires delivered to the same household. In the end, 1,675 parents returned the completed questionnaire, a response rate of 53 per cent. Of the parents questioned who stated their sex, 69.4 per cent were women (Table 1.2).

TABLE 1.1 Sample of pupils questioned, by gender and canton of residence

TABLE 1.2 Sample of parents responding, by gender and canton of residence

Dependent variable: atypicality of professional aspiration

The pupils were asked in particular to answer the following question: “What occupation do you hope to have when you are 30?” The responses were coded according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO). This is a classification devised by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1958, revised in 1968 and again in 1988 (International Labour Organization, 1991). We then asscribed to each ISCO code of the occupation wished for by the pupils the percentage of men in the same occupation on the basis of the data of the Federal Population Census 2000 (see Gianettoni et al., 2010 for an identical procedure). A score of 0 means that the profession is performed by 0 per cent of men in Switzerland, and a score of 1 means that the profession is performed by 100 per cent of men in Switzerland (and, for example, a score of .62 means that the profession is performed by 62 per cent of men). The higher this score is for boys the higher they aspire to typical occupations. Conversely, the higher the score is for girls, the less they aspire to typical occupations. Finally, we recoded this variable for boys (score *-1 + 1), in order to obtain a new variable where 0 is associated with a maximal typicality of the aspiration and 1 with a maximal atypicality of the aspiration.

Independent variables

Measures of sexism

We measured the degree of legitimacy of gendered roles and the hierarchy of the sexes using an adapted version of the sexism scale developed by Swim et al. (1995). The 13 items on this scale were adapted1 for young people after a pre-test. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each sexism score (old-fashioned and modern), separately for the pupils and the parents. As regards modern sexism, Cronbach’s alpha for the parents is good (.74) but lower for the pupils (.57). Reliability is weaker for the old-fashioned sexism scores: .55 for the pupils and .51 for the parents. Even eliminating some items from the scale, the Cronbach’s alpha did not improve. Moreover, a factor analysis on pupils’ and parents’ data confirms that the best solution consists of two dimensions: one including all the modern sexism items and the other all the old-fashioned sexism items. For this reason, we decided to use the composed scores but systematically checked that the results based on these scores were consistent with those obtained using the individual items.

Social class

Although sexism structures all social classes, members of lower social classes were found to adhere stronger to explicit sexist items when they feel precarious (Gianettoni & Simon-Vermot, 2010). Because of this possible co-variation between adherence to explicit sexist ideologies and social class, our regression analysis was controlled for indicators of social class. Each pupil was associated with the highest ISEI of both parents. The ISEI (International Socio-Economic Index) is an indicator of the position on a socio-economic scale devised by Ganzeboom, De Graaf and Treinman (Ganzeboom et al., 1992). This is a scale from 0 (very low) to 100 (very high) constructed on the basis of the weighted sum of the average number of years of education and the average income of occupation groups (...