![]()

Chapter 1: The Need to Understand Why Things Go Wrong

Safety Requires Knowledge

In the world of risk and safety, in medicine, and in life in general, it is often said that prevention is better than cure. The meaning of this idiom is that it is better to prevent something bad from happening than to deal with it after it has happened. Yet it is a fact of life that perfect prevention is impossible. This realisation has been made famous by the observation that there always is something that can go wrong. Although the anonymous creator of this truism never will be known, it is certain to have been uttered a long time before either Josiah Spode (1733–1797) or the hapless Major Edward A. Murphy Jr. (A more sardonic formulation of this is Ambrose Bierce’s definition of an accident as ‘(a)n inevitable occurrence due to the action of immutable natural laws.’)

A more elaborate argument why perfect prevention is impossible was provided by Stanford sociologist Charles Perrow’s thesis that socio-technical systems had become so complex that accidents should be considered as normal events. He expressed this in his influential book Normal Accidents, published in 1984, in which he presented what is now commonly known as the Normal Accident Theory. The theory proposed that many socio-technical systems, such as nuclear power plants, oil refineries, and space missions, by the late 1970s and early 1980s had become so complex that unanticipated interactions of multiple (small) failures were bound to lead to unwanted outcomes, accidents, and disasters. In other words, that accidents should be accepted as normal rather than as exceptional occurrences in such systems. (It was nevertheless soon pointed out that some organisations seemed capable of managing complex and risky environments with higher success rates and fewer accidents than expected. This led to the school of thought known as the study of High Reliability Organisations.)

Even though it is impossible to prove that everything that can go wrong will go wrong, everyday experience strongly suggests that this supposition is valid. There is on the other hand little evidence to suggest that there are some things that cannot go wrong. (Pessimists can easily argue that the fact that nothing has never gone wrong or not gone wrong for some time, cannot be used to prove, or even to argue, that it will not go wrong sometime in the future.) Since things that go wrong sometimes may lead to serious adverse outcomes, such as the loss of life, property and/or money, there is an obvious advantage to either prevent something from going wrong or to protect against the consequences. But it is only possible to prevent something from happening if we know why it happens, and it is only possible to protect against specific outcomes if we know what they are and preferably also when they are going to happen. Knowing why something happens is necessary to either eliminate or reduce the risks. Knowing what the outcomes may be makes it possible to prepare appropriate responses and countermeasures. And knowing when something will happen, even approximately, means that a heightened state of readiness can be established when it is needed. Without knowing the why, the what, and the when, it is only possible to predict what may happen on a statistical basis. There is therefore a genuine need to be able better to understand why certain things have happened, or in other words to know how to construct useful and effective explanations.

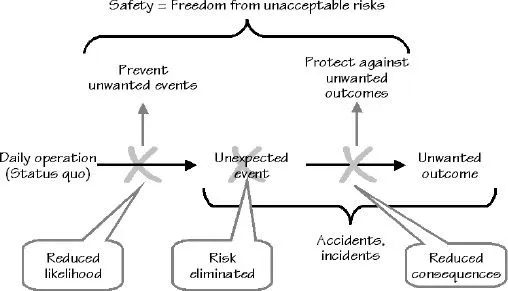

Despite the universal agreement that safety is important, there is no unequivocal definition of what safety is. Most people, practitioners and researchers alike, may nevertheless accept a definition of safety as ‘the freedom from unacceptable risks’ as a good starting point. This definition can be operationalised by representing an accident as the combination of an unexpected event and the lack of protection or defence (Figure 1.1). This rendering suggests that safety can be achieved in three different ways: by eliminating the risk, by preventing unexpected events from taking place, and by protecting against unwanted outcomes when they happen anyway.

In most industrial installations risk elimination and prevention are achieved by making risk analysis part of the design and by establishing an effective safety management system for the operation. Protection is achieved by ensuring the capacity to respond to at least the regular threats, and sometimes also the irregular ones.

Figure 1.1: Definition of safety

Although the definition of safety given in Figure 1.1 looks simple, it raises a number of significant questions for any safety effort. The first is about what the risks are and how they can be found, i.e., about what can go wrong. The second is about how the freedom from risk can be achieved, i.e., what means are available to prevent unexpected events or to protect against unwanted outcomes. The third has two parts, namely how much risk is acceptable and how much risk is affordable. Answering these questions is rarely easy, but without having at least tried to answer them, efforts to bring about safety are unlikely to be successful.

A Need for Certainty

An acceptable explanation of an accident must fulfil two requirements. It must first of all put our minds at ease by explaining what has happened. This is usually seen as being the same as finding the cause of why something happened. Yet causes are relative rather than absolute and the determination of the cause(s) of an outcome is a social or psychological rather than an objective or technical process. A cause can pragmatically be defined as the identification, after the fact, of a limited set of factors or conditions that provide the necessary and sufficient conditions for the effect(s) to have occurred. (Ambrose Bierce’s sarcastic definition of logic as ‘The art of thinking and reasoning in strict accordance with the limitations and incapacities of the human misunderstanding’ also comes to mind.) The qualities of a ‘good’ cause are (1) that it conforms to the current norms for explanations, (2) that it can be associated unequivocally with a known structure, function, or activity (involving people, components, procedures, etc.) of the system where the accident happened, so (3) that it is possible to do something about it with an acceptable or affordable investment of time and effort.

The motivation for finding an explanation is often very pragmatic, for instance that it is important to understand causation as quickly as possible so that something can be done about it. In many practical cases it seems to be more valuable to find an acceptable explanation sooner than to find a meaningful explanation later. (As an example, French President Nicolas Sarkozy announced shortly after a military shooting accident in June 2008, that he expected ‘the outcome of investigations as quickly as possible so the exemplary consequences could be taken.’) Indeed, whenever a serious accident has happened, there is a strong motivation quickly to find a satisfactory explanation of some kind. This is what the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche in The Twilight of the Idols called ‘the error of imaginary cause,’ described as follows:

[to] extract something familiar from something unknown relieves, comforts, and satisfies us, besides giving us a feeling of power. With the unknown, one is confronted with danger, discomfort, and care; the first instinct is to abolish these painful states. First principle: any explanation is better than none. … A causal explanation is thus contingent on (and aroused by) a feeling of fear.

Although Nietzsche was writing about the follies of his fellow philosophers rather than about accident investigations, his acute characterisation of human weaknesses also applies to the latter. In the search for a cause of an accident we do tend to stop, in the words of Nietzsche, by ‘the first interpretation that explains the unknown in familiar terms’ and ‘to use the feeling of pleasure … as our criterion for truth.’

Explaining Something that is Out of the Ordinary

On 20 March 1995, members of the Aum Shinrikyo cult carried out an act of domestic terrorism in the Tokyo subway. In five coordinated attacks at the peak of the morning rush hour, the perpetrators released sarin gas on the Chiyoda, Marunouchi, and Hibiya lines of the Tokyo Metro system, killing 12 people, severely injuring 50 and causing temporary vision problems for nearly a thousand others. (Sarin gas is estimated to be 500 times as toxic as cyanide.)

Initial symptoms following exposure to sarin are a runny nose, tightness in the chest and constriction of the pupils, leading to vision problems. Soon after, the victim has difficulty breathing and experiences nausea and drooling. On the day of the attack more than 5,500 people reached hospitals, by ambulances or by other means. Most of the victims were only mildly affected. But they were faced with an unusual situation, in the sense that they had some symptoms which they could not readily explain. The attack was by any measure something extraordinary, but explanations of symptoms were mostly ordinary. One man ascribed the symptoms to the hay-fever remedies he was taking at the time. Another always had headaches and therefore thought that the symptoms were nothing more than that; his vomiting was explained as the effects of ‘just a cold.’ Yet another explained her nausea and running eyes with a cold remedy she was taking. And so on and so forth.

Such reactions are not very surprising. Whenever we experience a running nose, nausea, or headache, we try to explain this in the simplest possible fashion, for instance as the effects of influenza. Even when the symptoms persist and get worse, we tend to stick to this explanation, since no other is readily available.

The Stop Rule

While some readers may take argument with Nietzsche’s view that the main reason for the search for causes is to relieve a sense of anxiety and unease, others may wholeheartedly agree that it often is so, not least in cases of unusual accidents with serious adverse outcomes. Whatever the case may be, the quotation draws attention to the more general problem of the stop rule. When embarking on an investigation, or indeed on any kind of analysis, there should always be some criterion for when the analysis stops. In most cases the stop rule is unfortunately only vaguely described or even left implicit. In many cases, an analysis stops when the bottom of a hierarchy or taxonomy is reached. Other stop rules may be that the explanation provides the coveted psychological relief (Nietzsche’s criterion), that it identifies a generally acceptable cause (such as ‘human error’), that the explanation is politically (or institutionally) convenient, that there is no more time (or manpower, or money) to continue the analysis, that the explanation corresponds to moral or political values (and that a possible alternative would conflict with those), that continuing the search would lead into uncharted – and possibly uncomfortable – territory, etc.

Whatever the stop rule may be and however it may be expressed, an accident investigation can never find the real or true cause simply because that is a meaningless concept. Although various methodologies, such as Root Cause Analysis, may claim the opposite, a closer look soon reveals that such claims are unwarranted. The relativity of Root Cause Analysis is, for instance, obvious from the method’s own definition of a root cause as the most basic cause(s) that can reasonably be identified, that management is able to fix, and that when fixed will prevent or significantly reduce the likelihood of the problem’s reoccurrence. Instead, a more reasonable position is that an accident investigation is the process of constructing a cause rather than of finding it. From this perspective, accident investigation is a social and psychological process rather than an objective, technical one.

The role of the stop rule in accident investigation offers a first illustration of the Efficiency-Thoroughness Trade-Off (ETTO) principle. Since the purpose of an accident investigation is to find an adequate explanation for what has happened, the analysis should clearly be as detailed as possible. This means that it should not stop at the first cause it finds, but continue to look for alternative explanations and possible contributing conditions, until no reasonable doubt about the correctness of the outcome remains. The corresponding stop rule could be that the analysis should be continued until it is clear that a continuation will only marginally improve the outcome. To take an analysis beyond the first cause will, however, inevitably take more time and require more resources – more people and more funding. In many cases an investigatory body or authority has a limited number of investigators, and since accidents happen with depressing regularity, only limited time is set aside for each. (Other reasons for not going on for too long are that it may be seen as a lack of leadership and a sign of uncertainty, weakness, or inability to make decisions. In the aftermath of the blackout in the US on 14 August 2003, for example, it soon was realised that it might take many months to establish the cause with certainty. One comment was that ‘this raises the possibility that Congress may try to fix the electricity grid before anyone knows what caused it to fail, in keeping with the unwritten credo that the appearance of motion – no matter where – is always better than standing still.’) Ending an analysis when a sufficiently good explanation has been found, or using whatever has been found as an explanation when time or resources run out, even knowing that it could have been continued in principle, corresponds to a criterion of efficiency.

We shall call the first alternative thoroughness, for reasons that are rather obvious. And we shall call the second alternative efficiency, because it produces the desired effect with a minimum of time, expense, effort or waste.

A Need for Simple Explanations

Humans, as individuals or as organisations, prefer simple explanations that point to single and independent factors or causes because it means that a single change or response may be sufficient. (This, of course, also means that the response is cheaper to implement and easier to verify.) An investigation that emphasises efficiency rather than thoroughness, will produce simpler explanations. The best example of that is in technological troubleshooting and in industrial safety. Yet we know that it is risky to make explanations too simple because most things that happen usually – if not always – have a complex background.

Another reason for preferring simple explanations is that finding out what has happened – and preparing an appropriate response – takes time. The more detailed the explanation is, the longer time it will take. If time is too short, i.e., if something new happens before there has been time to figure out what happened just before – and even worse, before there has been time to find a proper response – the system will run behind events and will sooner or later lose control. In order to avoid that it is necessary to make sure that there is time to spare. Explanations should therefore be found fast, hence be simple. The sustained existence of a system depends on a trade-off between efficiency – doing things, carrying out actions before it is too late – and thoroughness – making sure that the situation is correctly understood and that the actions are appropriate for the purpose.

The trade-off can be illustrated by a pair of scales (Figure 1.2), where one side represents efficiency and the other thoroughness. If efficiency dominates, control may be lost because actions are carried out before the conditions are right or because they are the wrong actions. If thoroughness dominates, actions may miss their time–window, hence come too late. In both cases failure is more likely than success. In order for performance to succeed and for control to be maintained, efficiency and ...