![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to platform businesses

Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate. Something interesting is happening.

Tom Goodwin

In 2007, designers Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia struggled to pay their rent in San Francisco when they noticed that the city’s hotels were fully booked for an upcoming design conference. They came up with the idea of renting out three airbeds in their loft and cooking breakfast for their guests. The next day, they designed a website, originally called airbedandbreakfast.com. In less than a week, they had three guests, paying $80 each a night. When the guests left, thinking this could become a big idea, they asked a former roommate of Joe’s, engineer Nathan Blecharczyk, to help them develop the site that we know today as Airbnb.

For the first few years, the team failed to raise money. The vision of a trusted community marketplace for people to list, discover and share private accommodation around the world did not appeal to venture capitalists (VCs), who couldn’t see a big enough market. But Brian, Joe and Nathan persisted and found ingenious ways to keep going. In 2008, the company ran out of cash, so they had to find creative ways to make money quickly. As the presidential campaign was in full swing and both sides were keen to show support for their favourite candidates, the Airbnb team decided to sell special edition Cheerios cereal boxes for both presidential candidates called ‘Obama O’s’ and ‘Cap’n McCains’ for $40 each. They made $30,000 in a few weeks.

By early 2009, they were invited to join the Y Combinator, one of the leading incubator programmes in San Francisco, and got $20,000 of funding from well-known angel investor Paul Graham. A seed round of $600,000 led by Sequoia Capital followed shortly afterwards.1 Even so, the business did not take off. The Airbnb team realized that the photos of places advertised on their website were not appealing. According to Brian Chesky, ‘A web startup would say, “Let’s send emails, teach [users] professional photography, and test them.” We said, “Screw that.”’2 They rented a $5,000 camera and went door to door, taking professional pictures of as many New York listings as possible. Revenues doubled quickly to $400/week and the site started to grow. Brian knew at this point that it was not just about pretty pictures, but that Airbnb first had to ‘create the perfect experience [. . .] and then scale that experience.’ In April 2012, the team started monetizing the service by charging up to 15% on the bookings. More funding rounds followed,3 which enabled Airbnb to hire more staff to focus on the customer experience and market the platform in order to scale the business.

Their success came down to three things: ease of joining for host and guest; effective matching of hosts and guests; and safe and easy trans actions for all.

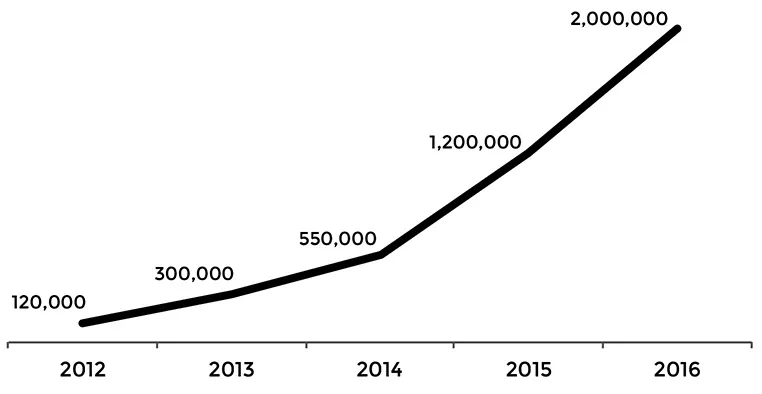

Since then, Airbnb has grown exponentially (see Figure 1.1), from 50,000 listings in 2011 to more than 2 million in April 2016.4 And this is not just inventory. It is estimated that roughly half a million people around the world sleep in an Airbnb rented accommodation at peak time.

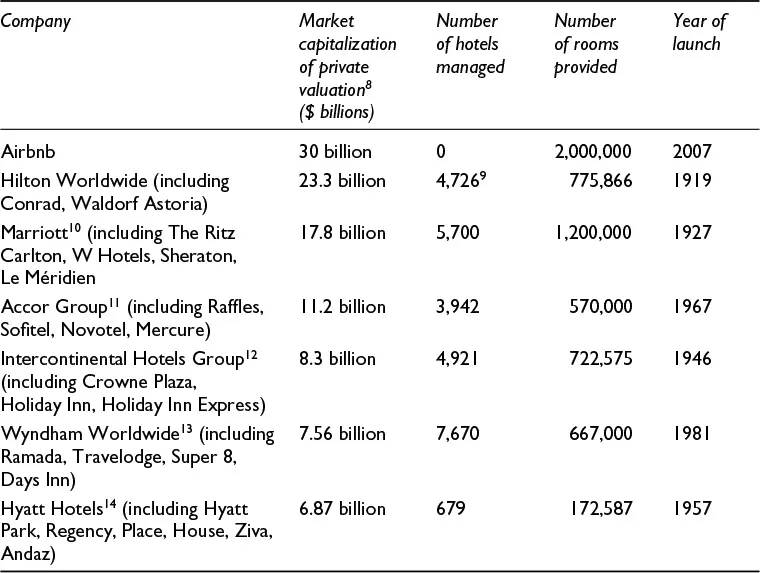

Airbnb is currently active in 34,000 cities in 190 countries, and has had 35 million nights booked.5 Airbnb raised $1.5 billion in June 2015, which is one of the largest private funding rounds ever. The company is estimated to be worth $30 billion,6 which means that in less than 10 years, the travel accommodation platform has become one of the most valuable privately owned start-ups, worth more than the largest hotel chains Wyndham, Intercontinental and Hyatt, who own extensive portfolios of prime real estate globally.

And Airbnb owns no property.

While there’s been an overwhelming response from customers, Airbnb’s high-growth success story has not been without resistance from hoteliers, who claim that individuals renting their rooms or entire homes to visitors represents an ‘unfair competition’ to their trade. There is emerging evidence7 that Airbnb is not only growing the market, but also increasingly competing against hotels, who have to respond with new services and lower prices. Interestingly, these lower prices benefit all consumers, and not just Airbnb clients. Yet Airbnb has also been under growing pressure from city authorities regarding housing regulations and tax laws. We’ll come back to these issues in Chapter 13 on platforms and regulation.

Table 1.1 Comparison of the largest hotel groups vs Airbnb

Unlocking Economic Value with Ebay

Using eBay as an example, let’s say that you have a large table with matching chairs that no longer fits with your newly redecorated flat. For you, this second-hand furniture almost has a negative value; it takes up space, and given the very reasonable price you paid for it at IKEA several years ago, you don’t want to spend time trying to find somebody to take this set off your hands. Conversely, think about a nearby student who has a tight budget and is looking for a table and chairs for her new pad. She wants to save money and doesn’t care about ‘new’ stuff. The student is prepared to pay £50 for the entire set. eBay can match you and this potential buyer, with very limited friction. Let’s say the student’s bid of £30 is the highest and that she is the happy winner of the auction. The value created by the platform intermediation is then £20 (£50 willingness to pay minus £30 winning auction bid) for the buyer plus £35 for the seller (that’s the £30 plus the negative price you were attaching to the no longer adequate table set that was taking up space: say £5). So out of ‘thin air’, the platform managed to create £55 of economic value. Now scale this by millions of transactions every day across all the platform companies (including car and house rental companies, e-commerce marketplaces, etc.) and you get a sense of the transformational potential of platform businesses.

Platform models have become mainstream

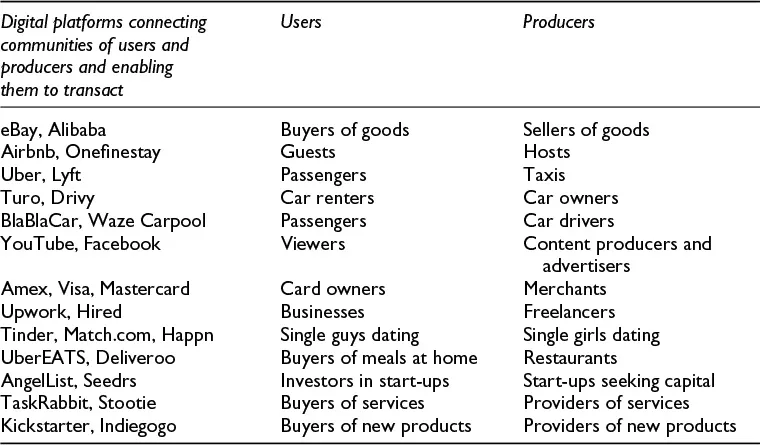

Airbnb epitomizes the rise of digital platform businesses. In the same way as eBay connects buyers and sellers, Airbnb creates communities of hosts and guests and enables them to transact globally. Unlike traditional businesses, platforms don’t produce anything and don’t just distribute goods or services. What they do is directly connect different customer groups to enable transactions. eBay, a well-known company, creates value by simply connecting buyers and sellers.

For thousands of years, markets have been physical and local. Connecting groups of buyers and sellers has played a big part in the fabric of human society. Farmers’ markets and matchmakers have been around for thousand of years. But something extraordinary has happened in the last 20 years: technology has enabled these business models to scale to a global level. The very first platforms that scaled globally were the credit cards companies such as Discover, Visa, Mastercard and Amex. But no one scaled as quickly or as globally as new technology-focused players such as Apple, Google and eBay, all underpinned by digital platforms.

Many more have followed suit, reinventing entire parts of consumer industries, from media (Facebook), retail (Amazon), transport (Uber), telecoms (WhatsApp), payments (PayPal), music (SoundCloud), accommodation (Airbnb) and many other sectors.

This platform colonization extends to the enterprise domain as well in an increasing number of verticals: wholesale goods (Alibaba), talent platforms (Upwork), operating systems (Windows), etc.

In most business literature, platforms are either considered as ‘black boxes’ serving what economists call ‘multisided markets’, or assumed to operate like traditional firms. Unfortunately, neither approach provides much insight into platform businesses themselves. Many commentators use the generic term ‘platform’ to describe a ‘technology platform’ that encompasses processors, access devices such as mobile phones, PCs and tablets, software applications, etc. These loose definitions often lead to vague notions of platforms that encompass firms with very different business models. We’ll come back for more detailed definitions of digital platforms in Chapter 3, but for the time being we’ll use a simple definition for platform businesses as those connecting members of communities and enabling them to transact. We’ll also define platform-powered businesses as firms that have parts of their business underpinned by platforms.

Table 1.2 Examples of digital platforms

Since many platform businesses are digital in nature, we use the term digital platform for businesses digitally connecting members of communities to enable them to transact.

Platform business models can be tailored to meet a wide range of needs. They include:

Marketplaces, which attract, match and connect those looking to provide a product or service (producers) with those looking to buy that product or service (users).

Social and content networks, which enable users to communic...