![]()

Part I

Motivation, Performance, and Effectiveness

The chapters in the first part of the book deal with the motivational conditions of performance at work. They aim at an understanding of fundamental motivational structures of achievement behavior that are crucial for the efficiency and effectiveness of work.

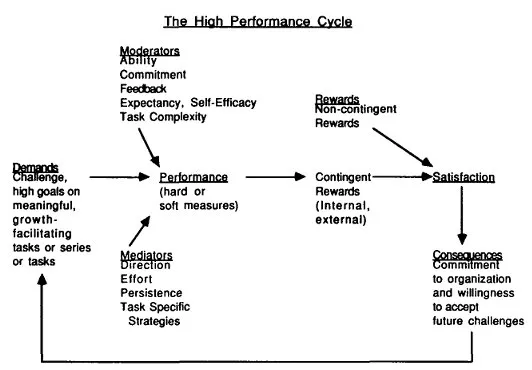

To characterize the motivational structure and dynamic of the achievement behavior, Locke and Latham have conceptualized a high performance cycle in the introductory chapter. They have outlined a theoretical framework in which the central variables of successful performance in organizations can be placed. Goal setting, feedback, mechanisms, and moderators of the transformation of goals into action constitute the focus of the discussion. The chapter by Kleinbeck and Schmidt demonstrates how one can get to empirical findings in the context of this theory. To analyze the differential effects of goals in information processing, determining performances, the technique of multiple goals in dual-task conditions was used. The authors have described a way to look at motivational and cognitive processes and the interaction between both.

On the background of a field study Antoni and Beckmann have looked at the effects of goal setting and feedback from the perspective of European action theory in the sense of W. Hacker and J. Kuhl. The authors stimulate further thoughts on modifying, adding, or refining concepts within the high performance cycle. Erez has addressed a classical theme of performance theory that traditionally was a topic of cognitive psychology: the relationship and exchange between quantity and quality. On the basis of a motivation approach to the problem she can show that the quantity– quality relationship and exchange can be explained in terms of motivation variables. At the end of the first part, Thierry has summarized the discussion on extrinsic and intrinsic motivation with respect to the behavior in organizations. His analysis of the contrary views led him to conclude that the distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation can no longer be made.

![]()

1

Work Motivation: The High Performance Cycle

Edwin A. Locke

University of Maryland

Gary P. Latham

University of Washington

Industrial-organizational psychologists have been studying motivation and satisfaction in the workplace for some five decades. For at least three reasons, however, progress in understanding these phenomena has been slow. First, it turned out that the motivation to work (exert effort) and satisfaction are relatively independent outcomes; thus somewhat different theories are required to understand them (Locke, 1970). Connecting the two types of theories has proven to be especially difficult (Henne & Locke, 1985). Theories that have tried to explain both phenomena with the same set of concepts generally have been unsuccessful. Second, theories within each domain, especially motivation–performance theories, have focused only on a limited aspect of the domain such as needs (Maslow, 1970), perceived fairness (Adams, 1965), or managerial motives (Miner, 1973). Third, the phenomena themselves are highly complex; thus extensive research has been required to understand them irrespective of any attempts to connect them.

It is now possible, however, to piece several of these theories together into a coherent whole. This integrated model cannot only explain, in terms of broad fundamentals, both the motivation to work and job satisfaction; it can specify key interrelationships between them. For purposes of simplicity we describe this model in terms of a single, interrelated sequence of events. We call this sequence the high performance cycle. It is outlined in Fig. 1.1. This model is restricted primarily to the individual level of analysis, though there is evidence that the same principles apply to groups and organizations (Latham & Lee, 1986; Locke & Latham, 1984; Smith, Locke, & Barry, in press). For purposes of simplicity, the model omits other possible causal paths as well as possible bidirectional causal relationships.

FIG. 1.1 The High Performance Cycle.

DEMANDS (CHALLENGE)

The model starts with demands being made of or challenges provided for the individual employee or manager. The theoretical base for this part of the model is goal-setting theory (Locke, 1968, 1978; Locke & Latham, 1984; Locke, Shaw, Saari, & Latham, 1981). This theory (based on earlier work by Ryan, 1970 and others) asserts that performance goals or intentions are immediate regulators or causes of task or work performance. Goal-setting research has shown repeatedly that people who try to attain specific and challenging (difficult) goals perform better on tasks than people who try for specific but moderate or easy goals, vague goals such as “do your best,” or no goals at all. This finding, replicated in close to 400 studies (Locke & Latham, 1990), has been verified by both narrative or enumerative reviews (Locke et al., 1981) and meta-analyses (Mento, Steel, & Karren, 1987; Tubbs, 1986). These findings have shown external validity across a wide variety of tasks from simple reaction time to scientific and engineering work, as well as across laboratory and field settings, hard and soft performance criteria, quantity and quality measures, and individual and group situations (Latham & Lee, 1986). The findings also generalize outside North America (Erez, 1986; Punnet, 1986; Schmidt, Kleinbeck, & Brockmann, 1984).

The finding of goal-setting theory, that performance is a positive function of goal difficulty (assuming adequate ability), is at odds with achievement motivation theory. Achievement motivation theory (Atkinson, 1958) asserts that maximum motivation will occur at moderate levels of difficulty where the product of probability of success (PS) and the incentive value of success (assumed to be 1–PS) is highest (assuming the motivation to succeed is stronger than the motivation to avoid failure). However, the curvilinear, inverse-U function originally obtained by Atkinson (1958) has proven quite difficult to replicate (Arvey, 1972; Locke & Shaw, 1984; McClelland, 1961; Mento, Cartledge, & Locke, 1980). Two problems with that model are the failure to include an explicit goal-setting stage and/or the failure to measure commitment to succeeding. These factors are crucial to predicting the individual's response to subjective probability estimates (Locke & Shaw, 1984).

Goal-setting theory is also seemingly at odds with expectancy theory, which was first introduced into industrial-organizational psychology by Vroom, (1964). This theory asserts that, other things being equal, expectancy of success (which is inversely related to goal difficulty) is positively related to performance. However, as shown later, goal-setting theory and expectancy theory can be fully reconciled.

Challenging goals are usually implemented in terms of specific levels of performance to be attained (e.g., 50 assemblies completed in 8 hours; 10% improvement in sales in 6 months). There are, however, alternative forms in which to present a challenge, e.g., a specific amount of work to be completed (White & Locke, 1981); the frequency with which specific job behaviors are to be engaged in (Latham, Mitchell, & Dossett, 1978); a deadline to be met (Bryan & Locke, 1967); a high degree of responsibility (Bray, Campbell, & Grant, 1974); or a budget to be attained (Stedry, 1960).

There are several different sources of job demands or challenges. They may come from authority figures such as supervisors, managers, or the CEO (Bray et al., 1974). They may come through a joint decision on the part of the boss and a subordinate (participation). Demands may also come from peers either as direct pressure to perform at a certain level or in the form of role models (Earley & Kanfer, 1985; Rakestraw & Weiss, 1981). Direct peer pressure to restrict output has been observed frequently, including in the famous Hawthorne studies (Roethlisberger & Dickson, 1939). However, there can also be peer pressure to not produce below a certain minimum or to produce at a high level (Seashore, 1954). Goals, deadlines, and high workloads can also be chosen by the individual employee in the form of self-set goals. Research on “level of aspiration” in the 1930s and 1940s found that self-set goals were affected by past successes and failures and by personality factors (Lewin, 1958). More recently it has been argued that Type A personalities, specifically those high in job involvement, are especially likely to put high demand on themselves (Kirmeyer, 1987; Taylor, Locke, Lee, & Gist, 1984). Finally, demands can stem from forces external or partly external to the organizations such as unions, bankers, stockholders, competitors, or customers.

Goal-setting theory approaches the explanation of performance quite differently from that of motive or need theories such as those of McClelland and Maslow. Whereas needs and (subconscious) motives are crucial to a full understanding of human action, they are several steps removed from action itself (Locke & Henne, 1986). Goal-setting theory was developed by starting with the situationally specific, conscious motivational factors closest to action: goals and intentions. It then worked backwards from there to determine what causes goals and what makes them effective. In contrast, need and motive theories started with more remote and general (often subconscious) regulators and tried to work forward to action, usually ignoring situationally specific and conscious factors. Generally the specific, close-to-action approaches (including goal-setting theory; social-cognitive theory, Bandura, 1986; turnover intentions theory, Mobley, 1982) have been far more successful in explaining action than the general, far-from-action approaches that stress general, subconscious needs, motives, and values (Locke & Henne, 1986; Miner, 1980; Pinder, 1984).1 The interrelationship between the two types of theories and sets of concepts is highly complex and not yet fully understood. For example, need for achievement (measured as a subconscious motive using the TAT) has been found to be unrelated to goal choice (Roberson-Bennett, 1983). But the value for achievement, a conscious motive that is not correlated with n ach, has been found to be significantly related to goal choice (Matsui, Okada, & Kakuyama, 1982; Steers, 1975).

We could hypothesize that one way that general needs, motives, and subconscious values could influence behavior is through their effects on situationally specific, conscious goals and intentions in conjunction with perceived situational demands.

In summary, the precursor of a high level of work motivation will be present when the individual is confronted by a high degree of challenge in the form of a specific, difficult goal or its equivalent. We say precursor because being confronted by a challenge does not guarantee high performance. There are at least five known factors or moderators that affect the strength of the relationship between goals and action.

MODERATORS

Ability

It is obvious that ability limits the individual's capacity to respond to a challenge. Goal-setting research has found that the relation of goal difficulty to performance is curvilinear after the limit of ability has been reached (Locke, 1982; Locke, Frederick, Buckner, & Bobko, 1984a). Further, there is some evidence that goal setting has stronger effects among high- than among low-ability individuals, and that ability has stronger effects among high-goal than among low-goal individuals (Locke, 1965a, 1982). One reason for the latter finding is that, when goals are low and people are committed to them, output is limited to levels below the individual's capacity.

Commitment

Challenging goals will lead to high performance only if the individual is committed to them. The effect of variation in goal commitment on performance is shown in phase II of Erez and Zidon's experiment (1984); it was found that, as commitment declined in response to increasing goal difficulty, performance declined rather than increased.

At least four classes of factors affect goal commitment (Locke, Latham, & Erez, 1988). The most powerful of these appears to be what French and Raven (1959) termed legitimate power or authority. Authority in the form of the experimenter in the laboratory or the manager at the workplace has been sufficient to guarantee high goal commitment in the overwhelming majority of goal-setting studies. The “demand” aspect of the experimental setting has been documented b...