![]() Part 1

Part 1

Nature, Sources, and Measurement of Heavy Work Investment (HWI)![]()

1

A General Model of Heavy Work Investment

Introduction

Raphael Snir and Itzhak Harpaz

By the term workaholics, Oates (1971) refers to people whose need to work has become so exaggerated that it may constitute a danger to their health, personal happiness, interpersonal relations, and social functioning. Since 1995, the number of publications on the topic of workaholism appears to be increasing exponentially (Sussman, 2012). Studies of workaholism resulted initially in a large volume of clinical and anecdotal data (e.g., Killinger, 1991; Machlowitz, 1980; Waddell, 1993), causing scholars to lament the lack of conceptual and methodological rigor (e.g., Scott, Moore, & Miceli, 1997). Recent studies have adopted better procedures, resulting in quantitative data that are amenable to statistical analysis (e.g., Bakker, Demerouti, & Burke, 2009; Chamberlin & Zhang, 2009; Harpaz & Snir, 2003; Russo & Waters, 2006; Schaufeli, Taris, & van Rhenen, 2008; Shimazu, Schaufeli, & Taris, 2010; Stoeber, Davis, & Townley, 2013). Yet despite the common use of the term “workaholism,” little agreement exists as to its meaning beyond its core element: heavy work investment.

This chapter, which constitutes an updated version of Snir and Harpaz’s (2012) paper, serves two main objectives. The first is to stress that workaholism is only one of the subtypes of heavy work investment. Namely, every workaholic is a heavy work investor, but not every heavy work investor is a workaholic. The second is to propose a model in which, using Weiner’s (1985) attributional framework, we differentiate situational from dispositional types of heavy work investment, each with its own subtypes, as based on the predictors of such an investment.

Several writers have focused on the negative aspects of workaholism (e.g., Killinger, 1991; Porter, 1996; Robinson, 1989, 2007; Schaufeli, Shimazu, & Taris, 2009; Taris, Schaufeli, & Verhoeven, 2005). For instance, Robinson (1989) defines workaholism as a progressive, potentially fatal disorder of work addiction, leading to family disintegration and an increased inability to manage work habits and life domains. Rooted in the addiction paradigm, one of the earliest measures of workaholism is the Work Addiction Risk Test (WART; Robinson, 1989). Workaholism, as measured by WART, includes five dimensions: Compulsive Tendencies, Control, Impaired Communication/Self-Absorption, Inability to Delegate, and Self-Worth (Flowers & Robinson, 2002). Nevertheless, despite Robinson’s quite extensive use of the WART, its external validity needs additional examination. With few exceptions (e.g., Taris, Schaufeli, & Verhoeven, 2005), most samples have included students (that are typically young and do not necessarily work), members of Workaholics Anonymous (which constitute a biased/range-restricted sample), or psychotherapists as expert observers (e.g., Flowers & Robinson, 2002; Robinson, 1996, 1999).

According to Schaufeli, Shimazu, and Taris (2009), workaholism is negatively conceptualized as working excessively and working compulsively. Based on this conceptualization, they propose a two-scale, ten-item workaholism measure, dubbed the Dutch Workaholism Scale (DUWAS). Satisfactory psychometric properties of the DUWAS are indicated (e.g., Del Libano, Llorens, Salanova, & Schaufeli, 2010; Schaufeli, Shimazu, & Taris, 2009).

On the other hand, some writers view workaholism positively, as involving a pleasurable engagement at work (Machlowitz, 1980; Sprankle & Ebel, 1987). For example, Machlowitz (1980:16) found that “as a group, workaholics are surprisingly happy. They are doing exactly what they love—work—and they can’t seem to get enough of it.” Likewise, Snir and Zohar (2008) found that workaholics experience more positive affect during work than during leisure activity, by comparison to nonworkaholics. Moreover, they found no significant differences between workaholics and non-workaholics regarding the likelihood of performing work-related activities during leisure activity, or in the levels of physical discomfort and negative affect during the weekend. This suggests no indications of work addiction, such as the inability to stop working, and withdrawal symptoms.

Other writers differentiate negative from positive workaholism types. For example, Scott, Moore, and Miceli (1997) identify three types of workaholism patterns: compulsive dependent, perfectionist, and achievement oriented, and signify the first two as negative types, the third positive. Spence and Robbins (1992) based their characterization of workaholism on three attitudinal work-related properties: involvement, drive (due to inner pressure), and enjoyment. They define a workaholic as a person with high scores in work involvement and drive, and low scores in work enjoyment. They contrast this profile with work enthusiasm, defined as high involvement and enjoyment and low drive. Hence, instead of differentiating negative and positive types of workaholism, Spence and Robbins (1992) differentiate workaholism, being negative, from work enthusiasm, being positive. Work enthusiasm is similar to the recently introduced concept of work engagement, which refers to a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli, Shimazu, & Taris, 2009; Schaufeli, Taris, & Bakker, 2006). Based on the above conceptualization, Spence and Robbins (1992) developed a three-scale Workaholism Battery (Work-BAT), which is a widely used measure in workaholism research. Despite apparent polarity, Spence and Robbins (1992) reported that their largest sub-group (19 percent of the sample) scored highly in all three aforementioned work-related properties (i.e., involvement, drive, and enjoyment), and therefore labeled them enthusiastic workaholics. According to this finding, work drive and work enjoyment are not opposites and can be viewed as orthogonal dimensions. Some research supports the psycho-metric properties of the Workaholism Battery (e.g., Burke 2001; Spence & Robbins, 1992), but its factorial structure is subject to some controversy (e.g., Huang, Hu, & Wu, 2010; McMillan, Brady, O’Driscoll, & Marsh, 2002).

Regardless of statistical properties, it is noteworthy that the Workaholism Battery is derived from three attitudinal constructs that partially overlap other well-established concepts: work involvement and drive are not entirely differentiated from work centrality and job involvement. This also holds regarding work enjoyment and job satisfaction. According to McMillan and O’Driscoll (2006), it is feasible that work drive and enjoyment are merely antecedents that trigger workaholic behavior. Finally, Spence and Robbins’ Workaholism Battery does not measure the feature that we consider a conspicuous aspect of workaholism: long work hours. That is, one may exhibit high involvement and high drive but work regular workdays. In our opinion, qualifying such an individual as a workaholic is erroneous.

The Proposed Model

The foregoing short description of the state of workaholism research indicates a great need for further theoretical and methodological development. As noted above, there is little consensus concerning the meaning of workaholism, as reflected in its negative versus positive conceptualizations, and the attitude–behavior controversy. There is also an implicit, though prevalent, assumption in the popular press and among practitioners that if one invests heavily in his/her work, he/she is most likely a workaholic (e.g., Downey Grimsley, 1999; Tuckman, 2006). In the present chapter we attempt to address these shortcomings, by introducing the two-dimensional concept of Heavy Work Investment (HWI), and

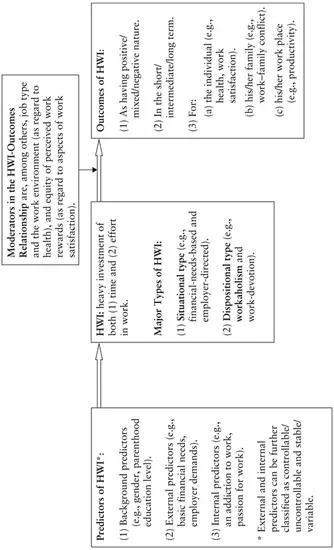

Figure 1.1 A model of Heavy Work Investment (HWI)

viewing workaholism as only one of its subtypes. Furthermore, we propose a model, presented in Figure 1.1, consisting of four main components: HWI, its possible predictors, its major types, and its outcomes.

The model shows the major sets of variables and the most straightforward relationships considered to be of primary importance in the study of HWI. The arrows indicate that an attempt should be made to determine the extent to which variables of one set predict (in a statistical sense) variables of another set. Possible moderators in relationship between HWI and its outcomes are also outlined.

Heavy Work Investment (HWI): A Two-Dimensional Concept

The shortcomings of previous workaholism research led Snir and Zohar (2008) to define workaholism as heavy time investment in work that does not stem from external demands (e.g., financial needs). This behavior-based definition does not overlap possible attitudinal predictors (e.g., work centrality, job involvement) or outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction). However, assessment of workaholism merely according to the time dimension (e.g., Harpaz & Snir, 2003; Snir & Harpaz, 2004) is somewhat simplistic, since it disregards how one acts during working time. According to Jacobs and Gerson (2004), the intensity of work is as important as the amount of time it takes. Thus, a second important dimension that should be considered is effort. This means the amount of either physical or mental energy allocated to work (Becker, 1985). Indeed, workaholics are intense, energetic, and competitive (Machlowitz, 1980). Naughton (1987) asserts that workaholics demonstrate endless energy in their work settings. Clark et al. (1993) also reported a positive correlation between workaholism and energy levels.

In our view, while non-stemming from external demands is a specific workaholism feature, time and effort investments in work constitute the two core dimensions of HWI in general. The HWI concept incorporates these two core dimensions while eschewing a priori positive or negative associations (an example of the latter being the term workaholism, patterned after alcoholism). Consequently, one can test positive and negative outcomes without risking criterion contamination.

A question may be raised, though, whether a heavy work investor has to be high on both dimensions in order to be classified as such. There are some indications that time and effort investments in work are positively correlated. For instance, according to an Experience-Sampling study, in which respondents provided randomly sampled self-reports over a one-week period, daily work hours were found to be strongly correlated with performing work-related activity and thinking about work-related issues (Snir & Zohar, 2008). Contradictory examples easily come to mind: staying late in the office (while in fact hardly working) just to impress the boss; or by contrast, working intensively only for a limited duration (e.g., at peak hours). However, using McMillan and O’Driscoll’s (2006) terminology, we suggest that both high frequency (i.e., time) and intensity (i.e., effort) are core dimensions of HWI. Similarly, Hewlett and Buck Luce (2006) claim that Extreme Jobs demand a high number of work hours (60 or more a week), as well as having five or more out of ten specific characteristics such as fast-paced work under tight deadlines, an unpredictable flow of work, and an inordinate volume of work that amounts to more than one job.

Predictors of HWI

Broadly, there are three main categories of possible predictors of HWI: background variables, external (to the person) variables, and internal (to the person) variables.

Background Predictors

Among the most relevant background predictors of HWI are gender and parenthood. For example, in a cross-national study workaholism was found to be primarily a male phenomenon (Snir & Harpaz, 2006). Wharton and Blair-Loy (2002) state that employed women in the industrialized world continue to bear more responsibility for family and children than do their male counterparts so they are more often considered candidates for part-time work. According to a cross-national study of industrialized countries, for wives, being a parent was associated with a reduction in hours of paid work in all ten countries (Jacobs & Gornick, 2002). Rothbard and Edwards (2003) found that for women, increased time investment in either work or family reduced time invested in the other role. However, for men, increased time invested in work reduced time invested in family, but increased time investment in family did not affect time invested in work. Time invested in family was positively related to the number of children at home. In a recent study Snir, Harpaz, and Ben-Baruch (2009) found that a contrasting parenthood effect on men and women prevails even in the demanding high-tech sector, where women are expected to work long hours and play down their care-giving activities. Fathers invested more weekly hours in work than childless men, whereas mothers invested fewer weekly hours in work than childless women.

A third relevant background predictor of HWI is education leve...