Chapter 1

Personal space of the body

The core of the private sphere is the sphere that is closely associated with the human body. In this chapter, we focus on the body: its inner space of subjectivity as well as the psychological-physical space which is body’s extension to its immediate surroundings. We will search for the implications of such divisions as between inner self and others, between personal and interpersonal, for an understanding of the division between private and public spheres. We also look at how some non-Western cultures approach the notion of the self and the private space of the body.

The division of urban space into the public and private is a physical manifestation of the relationship between private and public spheres in society. In turn, these spheres are one reflection of the deeper level relationship between the individual and society, between the self and the other. This chapter focuses on the debates about this relationship between self and other. This will provide a first step in our investigation into the relationship between the private and the public, as it examines how individuals relate to themselves and to the world around them. It then discusses how different modes of analysing this relationship have produced different approaches to urban space and to the demarcation of the public and private spheres within it.

We then move out of the interior space of the body to the outside world, to find out how public and private spaces are constituted around the body. A major form of space, which lies at the heart of private sphere, is explored. It is personal space, a socio-psychological, invisible, and yet physical personal space around each individual, which others may not enter without consent. We explore the nature and dimensions of this personal space and the role it plays in the constitution of the private and public spheres.

INNER SPACE OF THE SELF AND OUTER SPACE OF THE WORLD

To understand the relationship between the public and the private realms, we have to start from one of the most fundamental divisions of space, that between the inner space of the self and the rest of the world. It is a commonly held belief that the mind is the innermost part of a conscious human being, his/her most private space. The public domain, whether on television screens or in the middle of streets, appears to be accessible to all, while the inner world of the mind is clearly beyond such access. An individual’s thoughts, feelings and desires can all be kept secret inside a box, the inner space of the mind, or be made public when it is felt appropriate to do so. The mental world of consciousness becomes the most basic manifestation of privacy because it is the realm which only one individual is aware of and has access to. I may not have complete control over my mental state but it is still best known to me and not to others. It feels to be outside the material world and as such beyond the reach of anyone else.

For some, this private space is where they can take refuge from the outside world, to relax, to make sense of the world, or to feel in control. In contrast, some may feel trapped inside this private space, unable to reach out, while others may be afraid of entering it, preferring to spend their time always in the company of others, for fear of turbulent feelings, bad dreams, or boring loneliness. The distinction between the private and public, therefore, starts here, between the inner space of consciousness and the outer space of the world, between the human subject’s psyche and the social and physical worid outside. The way we make this fundamental distinction has a direct impact on all forms of institutionalized public-private distinctions in our lives.

The discussions of the relationship between the two realms of the inner self and the outer world often revolve around two foci: the relationship between body and mind and the question of autonomy of the self. Each of these two themes has emerged first as a general classical notion, to be later challenged and altered through critical responses.

MIND AND BODY

To study the distinction between the inner and outer realms, it is essential to study the characteristics that distinguish them from each other, the borders that separate them and mediate between them, and the relationships between them. The inner space is seen to be the non-physical, soft space of thoughts and feelings, which grasps the world but is distinctive from the hard physical reality of the outside. This apparently common sense contrast formed the basis of what is now termed Cartesian dualism. For Descartes, the mind (a term he used interchangeably with ‘soul’) is essentially non-physical and has a real distinction from the body (Cottingham, 1992b:236). Descartes argued that the essence or nature of the mind consists of thinking and it is free of place or material things: ‘…this ‘I’, that is to say, the mind, by which I am what I am, is entirely distinct from the body’ (Descartes, 1968:54). Descartes was working within a religious as well as scientific frame of discussion, in a period dominated by sceptical arguments, prevalent among them Montaigne who wrote of ‘the soft pillow of doubt’ (Koyré, 1970:x). Descartes, however, was searching for certainty in knowledge. He aimed to put to one side all that he had been taught and tried to find a solid, rational foundation for his philosophy, which he found in thinking: ‘I think, therefore I am’ (Descartes, 1968:53). The theme of the self thus became the central theme of modern philosophy since Descartes (Scruton, 1996:481). The shape that Descartes gave to this theme four centuries ago has framed the discussion ever since.

As with any other form of public-private distinction, this separation of the inner and outer space relies on a boundary, which in this case is the human body. It feels that the mind is hidden in the head, but understands the world through bodily senses and can communicate with others through gestures, patterns of behaviour, and language, i. e. through the body. The non-physical, inner, private space of the mind is thus highly dependent on the body to grasp the physical, outer space of the world. In other words, the body mediates between the states of consciousness and the world. The body is the boundary between the two realms. It is the medium through which the two realms are related to each other (Figure 1.1).

Many commentators have since questioned Descartes’ dualism, so that many today would identify themselves as anti-Cartesian (Cottingham, 1992a: 1; Žižek, 1999). Cartesian dualism has been criticized on the ground that it separates the mental from the physical and the ‘inner’ mental states from the ‘outer’ circumstances (Scruton, 1996:48). Criticism of dualism often leads to some form of materialism, widely held by philosophers today, which rejects the possibility of the existence of consciousness outside the physical world. While dualists stress that the mental is irreducible, the tendency of the materialists is to get rid of the mental phenomena and reduce them to some form of the material or physical (Searle, 1999:46–9). Even those who reject such reductionist materialism, stress that consciousness is a biological process taking place in the brain (Searle, 1999:53).

Criticisms have also come from scientists, who argue that clinical observations have shown how drugs, head wounds and strokes change the state of the physical brain, which in turn changes the way people think and feel. This has made it difficult to accept the separation of a physical brain from a mental mind (Greenfield, 2000:56). For the neuroscientist Susan Greenfield, the mind is the personalized brain (2000:57). As we grow, networks of cells are formed, reflecting the individual experiences, which turn a generic brain (with its one hundred billion neurons) into a personalized mind. Consciousness is thus deepened as these agglomerations imbue each conscious moment with meaning (page. 164). For her, the mind and the self are synonymous terms: ‘After all, if mind is the personalization of the brain, then what more, or what less, could Self actually be?’ (page. 185–6). But the brain does not work in isolation. It is ‘in constant two-way traffic with the rest of the body’ (Greenfield, 2000:174). The integration of the body and mind leads to an understanding of how the mind is open to the influences of the body. This is particularly discussed in psychoanalysis, which posed a challenge to the classical notion of a pure mind disengaged from the body. Sigmund Freud (1985) investigated into the nature of, and the conflict between, conscious and unconscious contents of mind.

Normally, there is nothing of which we are more certain than the feeling of our self, of our own ego. This ego appears to us as something autonomous and unitary, marked off distinctively from everything else. That such an appearance is deceptive, and that on the contrary the ego is continued inwards, without any sharp delimitation, into an unconscious mental entity which we designate as the id and for which it serves as a kind of fagade—this was a discovery first made by psychoanalytic research…But towards the outside, at any rate, the ego seems to maintain clear and sharp lines of demarcation. (Freud, 1985:253)

The unconscious contents are desires and wishes, which function to obtain immediate satisfaction, with an energy coming directly from the primary physical instincts. There is no coordination or organization here, as each impulse seeks satisfaction independently of all the rest, to the extent that opposite impulses can flourish side by side. This, however, stands in sharp contrast with the more social and critical mental forces, which adapt to reality and avoid external dangers. Dreams are the outcome of such a conflict between the primary unconscious impulses and the secondary conscious ones (Strachey, 1985:19– 20).

1.1 The first boundary between the public and the private worlds is the human body, separating an inner self from the outside world (Paris, France)

The theories of Freud, with their precursors in early German idealism and in Nietzsche, develop a psychological critique of the subject, which is associated with a major intellectual current challenging the classical concept of the human subject (Honneth, 1995:261). This was in fact decentring the subjects, who were often unaware of their unconscious and whose coherence and integrity, therefore, was now being questioned (Rosenau, 1992:44–5). These discoveries show how the contents of the mind are diverse, conflicting and not transparent to the individual. They also show how the relationship between the inner space of the mind and the world is not necessarily logical and rational, but can be pre-linguistic and conflictual. All this contradicts those who believe that ‘everything specifically human in man is logos. One would not be able to mediate in a zone that preceded language’ (Bachelard, 1994:xxiii).

An implication of psychoanalytic findings for the public-private distinction is to see how there is a deeper level private space that is not accessible even to the individual who is its container. It might be said that the realm of unconsciousness is the innermost, and hence the most private realm of an individual. There may, however, be some problems with this argument, as public and private are clearly categories shaped by the exertion of various degrees of control, by the individual and by the society. That which lies outside access cannot be easily classified as public or private. But if it is taken to be a part of an individual, in the same way as any of the body organs are, then it falls within the private realm of an individual, but perhaps not in a privileged position above others.

Psychoanalysis was based on a belief in the liberatory powers of reason and the possibility of authority of the subject. If the unconscious desires are known and brought to consciousness, e.g. expressed through words, then the pathological consequences of the conflict between conscious and unconscious can be addressed. As a result, the subject can take charge and become autonomous. The fact that the subject’s mind was not transparent to him/her did not deny the subject the possibility of achieving such transparency.

But where does that leave the body in our analysis of the public and private realms? Does it belong to the public or the private sphere? It is clear that the patterns of access to the body and to the streams of consciousness within it are quite different. One is more accessible than the other and is hence less private. Whereas the body can be seen and touched by others, the mind is hidden, with a mental world that seems to be entirely within the private control of an individual. While access to the body is possible for others, access to the mental world is the privilege of the subject. Even when people share their minds and bodies in intimate relationships, there are always parts of the mind that are kept apart, consciously or otherwise. Therefore, the body, like any other boundary between two realms, finds an ambiguous role: it belongs to both spheres. On the one hand, it is the generator and the container of the inner space of consciousness and can be identified with it. On the other hand, it is one among many objects that make up the world. As we shall see later, the way this boundary, the public face of a human being, is treated is central to the way societies are organized.

Thus the investigations of philosophers, scientists and psychoanalysts have shown how the body and the brain work together in generating an inner realm of consciousness. The close integration of consciousness and the body shows how the working of the physical brain and the unconscious impulses generated by the body can directly shape the streams of consciousness, undermining the classical notion of a mind separated from the physical world of the body and in command of its realm. This poses a critical challenge to this most basic form of distinction between private and public realms. The unconscious and the consciousness, the mind and the body, as deeper manifestations of private and public realms, appear to have far more connection and continuity with each other than the simple distinctions suggest.

AUTONOMY OF THE SUBJECT

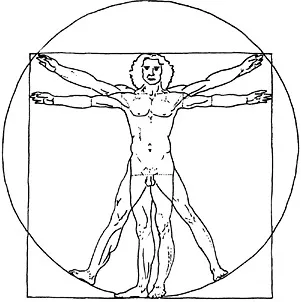

Another aspect of the relationship between inner self and outer world, closely related to mind-body dualism, is the question of individual autonomy, or in other words the question of power. The classical notion of the self that emerged in the Enlightenment presented it as ‘a stable centre incorrigibly present to itself and negotiating with its surrounding world from within its own securely established powers of knowing and willing’ (Dunne, 1996:139). It is in relation to this notion of the individual that the realms of the private and the public have been understood and shaped (Figure 1.2).

1.2 An independent self as ‘a stable centre incorrigibly present to itself and negotiating with its surrounding world from within its own securely established powers of knowing and willing’ characterized the modern world

According to Cartesian dualism, the subject is identical with his/her mind, and has a ‘privileged’, first-person view of it (Scruton, 1996:48). This view was developed and radicalized to intensify the first person authority. One form of radicalization of Cartesian dualism was idealism. It was rejected by Hume, who argued that when we have separated the mind and its ideas from the world, the result is that all that we have access to, or can accept to exist, is our own ideas (Politis, 1993). A major criticism of dualism and idealism came from Kant in his major work Critique of Pure Reason, who argued that ‘the world and how the world appears to us in experience are not two distinct things but two sides of one thing’ (Politis, 1993:xxx). Kant argued for ‘the transcendental unity of consciousness’ (Kant, 1993:B131). All the representations of the world that I receive are, or can be, connected to each other. I can call them my representations for I can comprehend them in one consciousness; ‘otherwise I would have as many-coloured and various a self as are the representations of which I am conscious’ (Kant, 1993:B133). Understanding, he argued, ‘is nothing more than the faculty of connecting a priori, and of bringing the variety of given representations under the unity of appreception. This principle is the highest in all human knowledge’ (Kant, 1993: B133–5).

Another form of radicalizing Cartesian thought has been phenomenology, as developed by Edmund Husserl at the beginning of the twentieth century (Schutz, 1962:102), starting a major philosophical tradition, through Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty, among others. With the help of philosophical doubt, Husserl aimed to show the implicit presuppositions that the sciences use in their analysis of the world. The Cartesian philosophical doubt was to be radicalized by two tools: ‘phenomenological reduction’ and ‘intentionality’. Phenomenological reduction used the technique of ‘bracketing’, which me...