eBook - ePub

The Death of the Irish Language

Reg Hindley

This is a test

- 364 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

The Death of the Irish Language

Reg Hindley

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Using a blend of statistical analysis with field survery among native Irish speakers, Reg Hindley explores the reasons for the decline of the Irish language and investigates the relationships between geographical environment and language retention. He puts Irish into a broader European context as a European minority language, and assesses its present position and prospects.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que The Death of the Irish Language est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à The Death of the Irish Language par Reg Hindley en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Politics & International Relations et Politics. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Part 1

Background

Chapter one

Irish before 1800

The Irish language is one of the Celtic sub-group of the Indo-european language family and is closely related to Scottish Gaelic, which only slowly broke away from it in the thousand years after Irish Gaelic speakers had set out to colonize south-west Scotland from around the fifth century A.D. Before that Gaelic seems to have been confined to Ireland, save for a few colonies in western mainland Britain, which was otherwise dominated by people speaking Brittonic languages from which modern Welsh and continental Breton are descended. In northern Britain the enigmatic Picts appear to have included Celts with Brittonic linguistic affinities and an older, more northerly group of different but pre-Indo-european speech, about which little is known and a great deal speculated.

Irish was thus a militantly expanding language until around A.D.1000 and did succeed in displacing its Brittonic rivals (including Strathclyde or Cumbrian Welsh) and Pictish in Scotland, even subDúing Northumbrian English in the Lothians, though impermanently. The firstrecorded external attacks on its supremacy in Ireland were those of the Norsemen from the early ninth century onwards. The Norsemen or Vikings are usually credited with the introduction of urbanism to Ireland, and especially the foundation of the historic port-cities, including Dublin, Cork, Galway, Waterford, Wexford, and Limerick, the last three of which still bear Norse-derived names. The areal extent of their displacement of the Irish language was none the less extremely limited and within two centuries they were almost entirely assimilated, very much as happened in Normandy, Rus (Russia), and the English Danelaw. Lack of numbers and lack of women settlers must have played a part here. The only significant areas in which the Norse language may have been established sufficiently well to lay the groundwork of future anglicization after the Anglo-Norman conquest which began in 1170 were Fingall in the north of present Co. Dublin and the so-called ‘English baronies’ of Forth and Bargy in the extreme south-east of Co. Wexford. There are obvious parallels here with the Norse settlements in Gower and the peninsula of southern Pembrokeshire in Wales, and with north-east Caithness in Scotland, all of which afforded later footholds for English in otherwise Celtic hinterlands. Fingall and south-east Wexford seem never completely to have reverted to Irish speech again.

The Anglo-Norman conquest rapidly enveloped the whole island and established the juridical supremacy of Norman French, relatively soon displaced by English for all but narrowly legal purposes. Yet in most parts of Ireland the conquest proved a veneer and the new landowners intermarried with native families, becoming themselves Irish speakers and indistinguishable from the native Irish to English officials and visitors. Laws enjoining the use of English and prohibiting the use of Irish in the courts and the corporate boroughs recur throughout medieval Irish history, the most comprehensive embodied in the Statutes of Kilkenny of 1366. The salient point is that they were felt necessary – again and again – because they were ineffective and Irish was always insidiously asserting itself despite its lack of legal status. The term ‘Old English’ had to be invented to distinguish great families which were conscious of their historic rights and status as conquerors for the Crown but who otherwise spoke and behaved like Irishmen and were just as inclined to revolt against royal authority.

Lack of numbers was again crucial. The Anglo-Normans were an elite group with relatively few plebeian settlers, almost everywhere enormously outnumbered by the native Irish, with whom intermarriage was inevitably attractive after initial antipathies. Inadequate medieval transport links could not maintain close relations with the home country, except again in a handful of coastal ports, and the only indigenous linguistic allies were the Norsemen of the tiny territorial pockets already referred to. Fingall with adjacent Dublin formed the core of the ‘English Pale’, a constricted area covering no more than Co. Dublin with parts of Meath, Louth, Kildare, and Wicklow. Even here the evidence points more closely to subjection to English law than to any consistent or exclusive use of the English language by the people at large. It must always be remembered that in pre-modern times government impinged little on everyday life, so unless there were other pressing reasons to learn English, e.g. for trade, there would be no cause to do so; nor would the government itself be concerned with the language of ordinary people.

It is remarkable that throughout medieval Irish history the province exhibiting least English influence was Ulster, from which Scottish missionaries and conquerors had earlier transferred their Gaelic language and their very name to Scotland. The latter had been known under various names, including Caledonia, Pictavia/Pictland, and Albania/Albany, but these applied only to the parts north of the Forth-Clyde isthmus and it was the Scots from Ireland who united as their kingdom the territories now known as Scotland. Linkages across the North Channel of course worked both ways and were even reinforced by the seafaring Norsemen. This meant that whenever the Anglo-Normans attempted to conquer or settle Ulster the northern Irish could always seek help or refuge in and from Scotland, and Scotland in turn valued Irish friends who could divert the attentions of the English when, as under Edward I, they threatened the survival of the Scottish state. The Donegal name Gallagher (in Irish Ó Gallchobhair) means ‘foreign help’ and is an ethnic marker similar to Walsh (Irish Breathnach), which is widespread in the South, signifies Welsh origin, and is often spelled and/or pronounced Welsh in Munster and Connacht. (See Mac Lysaght 1973.) The Welsh, however, came only as auxiliaries of the Anglo-Normans, whereas the Scots represented a balancing political and cultural force which despite the progressive linguistic anglicization of the medieval Scottish Mònarchy and the Lowlands continued to share the Gaelic heritage in the islands and peninsulas closest to Ireland.

The Tudors under Henry VIII and his successors undertook to pacify their turbulent Irish subjects by enforcing English law and imposing the English language. The Reformation is commonly credited with consolidating the attachment of the semi-hibernicized Old English to Irish customs and usages but it should also be remembered that the first modern-style attempt at English colonization outside the diminutive Pale was the carving out of King’s and Queen’s Counties (Offaly and Leix) from Irish lands under the Counter-Reformation Mary I and her consort Philip II of Spain in 1556. This met with violent resistance and experienced the usual shortage of ordinary English settlers much below gentle-man-adventurer level. Ireland had never attracted the English peasant class, for it combined a hostile population with a cooler and damper climate for agriculture. France had always been far more attractive to the English gentry too and it is scarcely coincidental that the effective end of English aspirations there with the loss of Calais (1558) was followed by their transfer to North America – not swiftly but after less than a century of struggles which confirmed that Ireland was no safe or profitable field for colonization.

The Marian plantation was a failure that disrupted traditional Irish proprietorship but left a solidly Irish under-tenantry, as no one else wanted their place and new landlords had no use for land without tenants to work it. Much the same applied to Elizabeth’s plantation of Munster in 1586 but the Ulster plantation of 1609 onwards was a different matter, for the Union of the Crowns of England and Scotland under James VI and I for the first time united British interests in the joint exploitation of Irish resources.

The agricultural potential of Ireland may have been uninviting to most English country men but was an attractive prospect viewed southerly from much of Scotland. Hence the prominent part played by Scots in providing the basic numbers on which the partial success of the ‘Great Plantation’ was founded. The plantation excluded three of the nine Ulster counties, and it is remarkable in terms of subsequent linguistic history that both Antrim and Down were excluded whereas Donegal was not. Again the geography of soils and accessibility by sea provide a readier explanation of the regionally varied progress of colonization than mere changes in land ownership, for new grantees found it very difficult to secure British tenants for poorer land or for land far removed from one of the new defended towns. Private initiative was also used by settlers keen to secure tenancies in the eastern coastal counties. In general the better land fell to immigrant Protestant settlers, and the hills and lowland bogs (as around Lough Neagh) were left to the native Irish Catholic tenantry. The latter can also be shown to have fared better in areas granted to the (Anglican) Church of Ireland, and some interesting anomalies in later denominational distributions relate to this. See for example the land ownership map of the Londonderry plantation in Moody (1939) and the religious map of Ireland for 1911, here map 2. The lowland ‘Catholic triangle’ marked on the latter at the mouth of Lough Foyle became Church land from 1609. The linguistic result of this was for about two centuries a quiltwork pattern of English- and Irish-speaking districts.

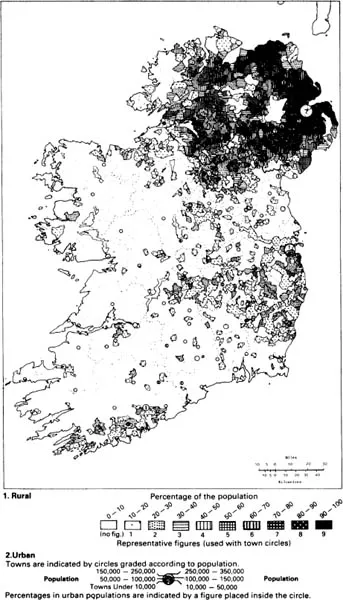

This pattern was not established at one blow, for colonization was severely disrupted by native revolts and concomitant wars which were at their most bloody in the Cromwellian and early Williamite periods. The net result was the almost total exclusion of Catholic landowners from Ulster but a major survival of native people in all but a few small and rich lowland areas. Map 2, compiled from the census reports of 1911, gives a good indication of the extent to which the English-speaking incomers were able to impress themselves on the province. The Protestant element represents the incomers, the Catholic group the native Irish, and although modifications of the pattern have undoubtedly occurred since the last wave of colonization which accompanied the Williamite settlement they consisted principally of the migration of native Irish people into the towns. The religious pattern and with it the pattern of British and Irish settlement was effectively fossilized in the early years of the eighteenth century, and it is most significant that almost everywhere where Catholics formed more than about 30–40 per cent of the population in 1911 there is evidence that Irish was still spoken by all or most of the indigenous inhabitants around 1800.

The Cromwellian settlement scheme of 1653 was grandiosely conceived to clear Leinster and Munster of Irish gentry and landowners and to plant all the corporate towns with ‘new English’. It did little to shake the hold of the Irish language among ordinary working people anywhere in the country but did greatly advance that alienation of the gentry from the people which was finally consummated at the end of the century. Without doubt many native Irish landowners changed their religion to save their estates but at the same time they usually accepted the advantages offered by cultivation of the English language in the pursuit of a peaceful civilized life which became a real possibility after the Boyne (1690) and final military pacification.

Map 2 Protestants by towns and district electoral divisions. Census 1911

The political instability and recurrent civil disorder of the seventeenth century made sheer survival the main concern of most Irish people and Ó Cuív’s review of contemporary sources shows that Irish remained current (if not dominant) in Dublin itself throughout the period (1951: 18). In many country districts outside the planted North its position was still so secure that descendants of Cromwellian settlers were commonly monoglot Irish by 1700. Thereafter it is fairly clear that the spread of the knowledge of English which radiated from the main cities and towns made such assimilation infrequent, but it is unlikely that Irish began to fall into disuse in native homes before about 1750, except in a handful of towns.

The onset and extent of the spread of English and abandonment of Irish among ordinary folk in eastern Ireland received scant attention from eighteenth-century writers, a few of whom remarked on language use at individual places; but there was no comprehensive survey and all that can be said with certainty is that by 1800 the gentry throughout the country were entirely anglicized in their first-language preferences and in most eastern and central Ireland spoke no Irish at all. Yet in very few districts was the language entirely extinct among the native population. Garrett FitzGerald (1984) has shown how the age-grouped Irish-language census returns of 1881 can be used to establish minimum levels of Irish speaking by baronies extending back to before 1800, thus developing earlier work by G. B. Adams (1964–79), who made use of the census returns from 1851 onwards and noted their limitations.

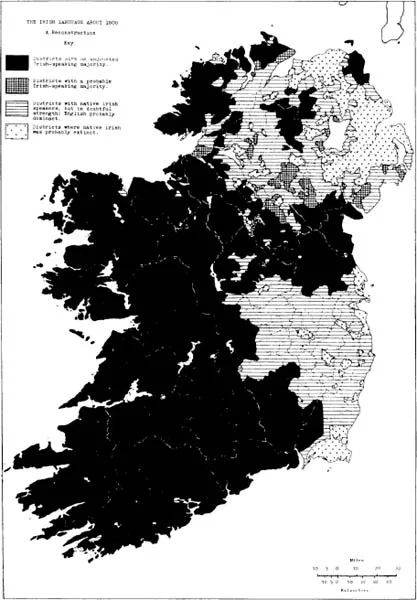

Map 3 here attempts to synthesize their conclusions and to merge them with inferences from the sources abstracted by Ó Cuív and evidence from the O’Donovan and O’Curry Ordnance Survey papers (c. 1834–40) in the Royal Irish Academy. Detail has been added in the Ulster counties on the following assumptions:

1. | That in 1800 the great majority of Catholics in the North spoke Irish as their native language. |

2. | That the detailed pattern of religious distributions in 1911 (when details were first published) gave a reliable indication of the patterns in 1800). |

In the first case, local ministers who commented on language usage at that time considered it remarkable if Catholics did not speak Irish, and in the second all reliable observers note the relative stability of religious strengths during the nineteenth century, except in the towns, where industrial growth brought a marked Catholic influx. In the country districts higher Catholic birth rates were countered by job discrimination plus higher mortality and emigration.

Map 3 The Irish language about 1800. A reconstruction based on literary sources and censuses 1851, 1881, 1911

From these two basic assumptions and a study of the contemporary evidence available it appeared to follow that in Ulster:

1. | Where over 70 per cent of the population in 1911 were still Catholic a clear majority of the people would have been Irish speakers in 1800. |

2. | Where there were over 30 per cent of Catholics in 1911 but less than 70 per cent, an Irish-speaking population would have been present in 1800, but of strength unknown, failing other evidence. |

3. | Where under 30 per cent were Catholics in 1911 there would be no Irish-speaking community at the earlier date. |

Only in one case, the parish of Ardstraw, south of Strabane, was reason found to assume the death of Irish in a district with over 30 per cent of Catholics (Mason 1814–19:I, 123), and one must allow the possibility that the reporting minister was not fully acquainted with the intimate lives and language of his Catholic parishioners, who would undoubtedly have been fluent in English but not necessarily to the total exclusion of Irish. That said, the map is merely an assessment of broad probabilities and cannot claim to be more.

The assumptions made for Ulster cannot be applied in the rest of the country, where in general the presence of much lower numbers and proportions of Protestants posed much less of a barrier to the economic and social advancement of Catholics and therefore did much less than in Ulster to remove the main reason they could have for the cultivation of English. In short, Ulster Protestantism imposed a sort of apartheid on the native Irish Catholics and by confining them to the lowest social strata and excluding them from all but menial employment gave them no incentive to learn English. The anti-Catholic ‘Penal Laws’ imposed after 16...

Table des matières

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Bradford Studies in European Politics

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Frontispiece

- Contents

- Tables

- List of maps

- A note on place-names

- Preface

- Acknowledgements and sources

- Part 1 Background

- Part 2 Locating the living language

- Part 3 Can Irish Survive?

- Appendices

- Appendix 2: Some problems in the rendering and identification of Irish place-names in the Gaeltachtaí

- Appendix 3: Gaeltacht national schools 1981-2 and 1985-6: numbers and proportions of pupils in receipt of grant (deontas) under the Irish-speaking Scheme (Scéim Labhairt na Gaeilge)

- Appendix 4: Estimates of effective Irish-speaking populations, based on national census statistics 1981, with adjustments based on deontas figures 1985-6

- Appendix 5: Gaeltacht summary, by county Gaeltachtaí

- Bibliography

- Index

Normes de citation pour The Death of the Irish Language

APA 6 Citation

Hindley, R. (2012). The Death of the Irish Language (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1626827/the-death-of-the-irish-language-pdf (Original work published 2012)

Chicago Citation

Hindley, Reg. (2012) 2012. The Death of the Irish Language. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1626827/the-death-of-the-irish-language-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Hindley, R. (2012) The Death of the Irish Language. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1626827/the-death-of-the-irish-language-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Hindley, Reg. The Death of the Irish Language. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2012. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.