![]()

1

On Imitation

The first time I was in Rome was when I was very young the pope was told about the discovery of some very beautiful statues in a vineyard near S. Maria Maggiore. The pope ordered one of his officers to run and tell Giuliano da Sangallo to go and see them…. Since Michelangelo was always to be found at our house, my father having summoned him and having assigned him the commission of the pope’s tomb, my father wanted him to come along, too. I joined up with my father and off we went. I climbed down to where the statues were when immediately my father said, “That is the Laocöon that Pliny mentions.” Then they dug the hole wider so that they could pull the statue out. As soon as it was visible everyone started to draw, all the while discoursing on ancient things, chatting as well about the ones in Florence.

Francesco da Sangallo (event 1506)1

Imitation is the first stage of apprenticeship to the past. It is an act of humility, but not of self-abnegation: one should not lose oneself in it, but find a voice. To be done well, it depends on passion and conviction, not easily had if one finds the effort tedious or the subject drudgery. So finding something to imitate that is inspiring, and a way to copy that suits one’s abilities, is an important part of the process, and these choices of subject and media often evolve over time. In the classical world, all art was understood to be mimetic, in the sense of imitating (or re-presenting) Nature—whether in a literal, documentary sense (in painting and sculpture), or in the representation of Nature’s underlying logic (in geometry and architecture). But artists also were formed in imitation of other artists. An artistic formation in imitation can be broken down into three aspects: direct replication of a specific model, or what we usually understand as copying; focused imitation of the style and techniques of a specific culture or group of artists (such as sixteenth-century Venetians, or the Carracci school); and immersion in the mind of a well-defined epoch (such as classical antiquity or the Renaissance). The first involves almost exclusively visual media, their manipulation, and an understanding of the forms to be represented (like anatomy, the idealized classical figure, or the classical orders of architecture); the second involves both immersion in visual exemplars—whether originals or reproductions—and creative experimentation with their working methods; while the last of the three is heavily weighted toward research, by reading and immersion in the culture of the model. If what one is after is more than mere simulacra or resemblances, but rather an embodiment of a deeper set of principles, then to be truly “inspired” one must breathe in the air of the place. To imitate is, to an extent, to submerge one’s own self in some larger or different “other.” To appreciate its distinction from emulation, it is useful to develop an appreciation for the complexities of copying and the mechanics of imitation.

The story of the discovery of the Laocöon, attended by Michelangelo, is especially notable for three things: a chance find is recognized due to a literary source (Pliny the Elder); the first thing everyone does when it is fully unearthed is draw; and this drawing sponsors a conversation about contemporary developments in the arts. Knowledge acquired through study inspires graphic production that engenders critical discourse. The model artist is thus informed, able, and articulate.

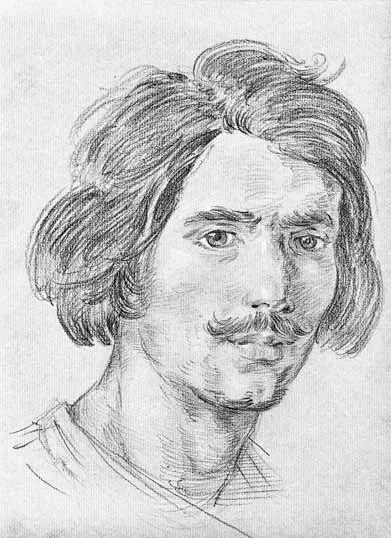

1.1 Copy after a self-portrait of Bernini

Apprenticeship could be real, or virtual. If all artists were formed for at least a time in a master’s studio, they all experienced a real apprenticeship, whether it was truly formative for them or not. But many artists pursued their own virtual apprenticeships, finding masters whom they wanted to emulate and engaging in imitative exercises to apprehend the skills and ideas they sought. These masters were available by means of their work, if often not their person. Desirous virtual apprentices sought out exemplary work and made copies, whether in drawing or in similar media to the originals. Peter Paul Rubens is paradigmatic of such an artist.

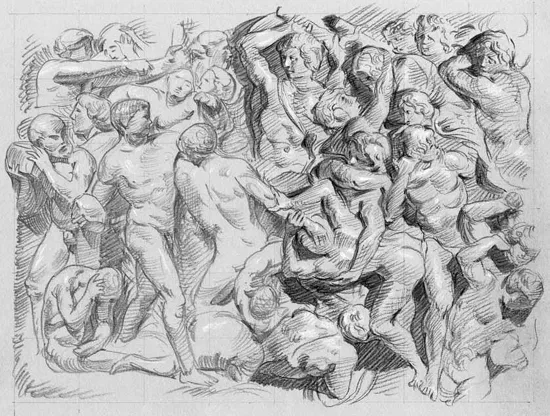

When Rubens was in Florence, he made a point of making two chalk copies of Michelangelo’s youthful relief of the Battle of the Centaurs and Lapiths. The Rubens’ copy in Rotterdam makes a fascinating study in the nature of copying, and the borders between that and emulation. Michelangelo’s marble was an early exercise in a complex interplay of contrapposto bodies, at once a series of figure studies and a compositional exercise; it is itself an emulation, conscious of antique relief precedents and descriptions (ekphrases) of sculpture. A relief discovered in Cortona in the thirteenth century shows a similar battle; just a year before Michelangelo perhaps began his relief (1492, when he would have been seventeen) Luca Signorelli painted a Virgin Enthroned with Saints which included a Centauromachy below the Virgin’s throne; and, of course, the famous south metopes of the Parthenon showed the same subject, although while these hadn’t been seen by Europeans for some time, they were well known from descriptions. Thus the teenage Michelangelo need not have had esoteric outside advice to have chosen the subject, even if being part of the Medici Academy meant he had access to Politian and other humanists.

While the common conception of Michelangelo is of an artist obsessively drawing the male body, even pursuing dissections to know better the inner workings of the figure, the Lapiths relief does not function as an anatomical exercise. Common sense says there was no way he was able to pose all those intertwined battling bodies in his studio, nor do the bodies reveal a particularly defined anatomical accuracy. Many of the figures lack the overt musculature of the ignudi from the Sistine ceiling, and seem instead more like what the artist’s own body must have been like at seventeen, when he probably carved it (one suspects that more than once—as in the case of his various hand studies—Michelangelo used himself as model). The relief has the quality of a sketch, and one can imagine the young artist challenging himself but perhaps also diving in without knowing precisely where it would lead. The relief doesn’t seem fully planned out: some figures are tentatively indicated, as if they were still in development, while others are finely resolved; hair is mostly unshaped masses of chiseled “stuff,” and expressions in these warriors are generally nonexistent. The figures look more like his early compositional studies for poses than his detailed drawings from life, and the complexity and small scale of the piece makes that almost inevitable. What is worth stressing in this context is that Michelangelo simultaneously documented anatomy with precision, and experimented with the body in every possible position from his imagination. His study of anatomy freed him, as the first preside of the Accademia di San Luca, Federico Zuccaro, would want, “to be able graphically to reconstruct the complex play of primary and secondary lights and projection of shadows, and the effect of foreshortening, without mimetically portraying (ritrarre) them from life.”2 The mental agility this afforded him made him master of the body and not, as would Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio be accused of a century later, a slave to the model.

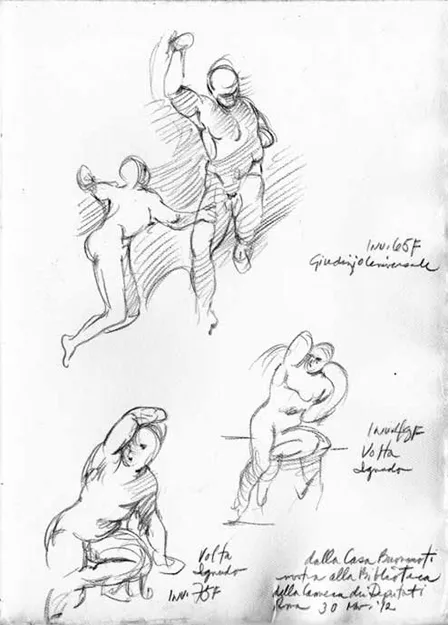

1.2 Copy after various studies for the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo

Michelangelo also copied the works of other masters, with complete fidelity; he used to tinge his copies and make them appear black with age by various means, including the use of smoke [note the role of painted smoke Andrea del Sarto’s Madonna of the Harpies], so that they could not be told apart from the originals. He did this so that he could exchange his copies for the originals, which he admired for their excellence and which he tried to surpass in his own works; and these experiments also won him fame.3

Vasari tells us that Michelangelo was recognized as an expert copyist in his youth, and it is little remarked upon that one of the things he supposedly copied was a German print, which he rendered in pen and ink. This is about the same time as his earliest experiments in carving, as he drifted away from the painter Ghirlandaio’s shop and toward the Medici’s sculpture garden “academy.” So it is curious to think that the experience of copying an engraving (whose maker, in Latin, would be credited as having sculpsit), went hand in hand with his development of a stone carving technique he would make his own, and allow him to fluidly move back and forth from paper to marble through analogous techniques. The role of drawing in Michelangelo’s formation takes a surprising turn in his early experiments in architecture. As Cammy Brothers points out in Michelangelo, Drawing and the Invention of Architecture, when Michelangelo trained himself as an architect, he did so not by drawing other buildings but by copying other’s drawings of buildings, most significantly from the collection of drawings assembled in the Codex Coner. But this is a process, I would argue, more allied with emulation, and we will return to it again.

1.3 Michelangelo(?), Study of Three Male Figures (after Raphael). Bridgeman Art Library International

1.4 Copy after Rubens after Michelangelo

Rubens came along to Florence a little more than a century later, at 23 an artist in early maturity, and on a diplomatic mission from his Gonzaga patrons. But he was still a student, as he would be all his life, and inevitably had to see how the divine Michelangelo had trained himself. Rubens had read his Vasari, knew of Michelangelo’s claw chisel carving style, and imitated his hatching technique as a draftsman. Like his virtual mentor, he employed drawing to suggest carving. Indeed, in his drawing after the Lapiths relief (in black chalk with white highlights, reinforced with grey wash) the hatching is pronounced, even exaggerated, announcing his familiarity with Michelangelo’s style and emphasizing the effects of the marble (which, in actual fact, varies from areas of polish to rough, barely articulate stone). It is telling to work through how and what Rubens saw and drew: he gave many of the figures indications of wavy hair nowhere found in the original; he hinted at facial expressions, and even definition, that is mostly missing in the marble; in some cases he misread the more inchoate anatomy, and imagined slightly different poses; in general he “completed” the unfinished figures, giving his drawing a greater sense of finish or wholeness than the original. The wash, likely added later (perhaps back at his lodging), deepened the undercutting that his memory suggested, and while more uniformly undercut than the original (which has areas of almost rilievo schiacciato juxtaposed with high relief), it effectively conveys the plasticity of Michelangelo’s forms; it also distinguished better between shadow and surface texture. Indeed, having copied his drawing myself, I found that the wash added a degree of sfumato and subtlety that turned the drawing on paper into a more effective evocation of marble sculpture (Plate 1).

By the standards of an eighteenth-century Prix de Rome winner, Rubens’ copy was rather loose and imprecise. But as the model for a whole camp of artists—the Rubenistes—his method is worth studying for what it would engender. He projected onto the relief his own sensibilities for variety of expressions and coloristic handling of surface, and made of it a more complete work than it is in fact. I would argue that his exaggerations, and the overlay of his own predilections, made of his copying exercise an analogous one to the intent of the original—not mere documentation, but self-study and advancement. Not, then, a case of emulation, but a self-assured exercise of copying without loss of identity.

On Copying

The fact that Michelangelo taught himself architecture by making copies of drawings, so different from the figure studies and dissections by which he taught himself anatomy, suggests that he saw the mimetic aspects of each art to be fundamentally different. As a sculptor and painter, his primary subject was the human figure in action; he was not particularly concerned with expression, nor with portraiture, much less with landscape, costume, or even perspective. The body was, in its ideal form, his primary and almost exclusive means of expression, and what it expressed can best be summarized as some negotiation or tension between stress (the ignudi, the Slaves) and rest (the Pietà, Bacchus). At that he had no equal, perhaps not even in antiquity. But in architecture his point of departure was other drawings (from the Codex Coner), of antiquities, and occasionally modern buildings. Why? I would argue that, in the end, Bernini was right when he said that Michelangelo was a divine architect (as opposed to sculpture, for which Bernini thought he was less than perfect), because “architecture is pure disegno.” Michelangelo saw architecture as a problem in manipulation of form, subjecting it to those operations to which he subjected the figure in a block of stone: excavation, torsion, compression, and tension. By imitating drawings, he acquired the means by which he could conceptually manipulate architectural form avante la forme, since buildings were not nearly as yielding as a block of stone, which later in life he wished could be changed or corrected even in progress (the Rondandini Pietà). His later architectural drawings, like those for the Porta Pia, are wrought with numerous pentimenti, where he seemed to be excavating, cutting and correcting, and building up again, in some graphic equivalent of both modeling and sculpting. Thus, his self-education via drawing served to facilitate his invention, not as an exercise in imitation.

Michelangelo’s self-education in architecture illuminates the complex understanding of disegno in Renaissance culture, which became the basis for artistic formation in the academies that emerged later in the sixteenth century. Some of that complexity is still there in English, where to design can mean to imagine or create, but it can also suggest “to draw.” Pietro Roccasecca has elucidated the precise interplay of three modes of drawing in the training of artists in the early decades of the Accademia di San Luca: “[T]here were three stages of learning disegno: copiare, copying the drawings or invenzioni of a master; ritrarre [the root of ritratto, or portrait], portraying from plastic or live models; and finally disegnare, composing a disegno d’invenzione or original ‘story.’” When Michelangelo was training himself by copying the drawings in the Codex Coner, he was learning to both document architecture and to think about and understand architecture; simply making a replica of another drawing was a mechanical exercise, not an intellectual one. This will be important for our later investigation of emulation, since it presumes a grasp of the intent of a model, which means it is as much an intellectual exercise as a manual one. Being able to make a direct copy was an important manual skill, but could not by itself ensure emulation; moreover, the intermediate step of translating nature into a two-dimensional graphic representation was essential to the formation of the capacity to truly disegnare, or draw from the imagination. That capacity to draw what one can not see existed in a reciprocal relationship with the capacity to extract lessons from another artist’s work, or not merely mimic their output.

In the Vocabulario degli Accademici della Crusca [the dictionary of the Tuscan linguistic academy], published in 1612, the term disegnare was defined as an intellectual activity of “ordering” and the associated capacity to represent its concepts through lines and marks. Its purpose was to create a composition, generally for an artistic, scientific, or technical project. The term ritrarre also had a cognitive dimension, being defined as the act of observing nature and then demonstrating and describing it (not solely by means of lines and marks on paper). Copiare, instead, had no intellectual connotation; it referred to the purely mechanical act of copying, be it a text by a scribe or a drawing, painting, or sculpture by an artist.4

There are several different ways to approach the mechanics of copying for a classical artist: literal copying, or the reproduction as accurately as possible of an original in the same material and often at the same size; free copying, or imitating an original in the same medium, not necessarily at the same size, with a modicum of license in replicating the original form; and what I would call transcription, or replicating an original in another medium (painting into drawing, marble into bronze or clay). Each of these places particular demands on the copyist, and each has different ends. Many artists in the Renaissance and Baroque periods made literal copie...