![]()

1 Introduction

The history of twentieth-century China is punctuated with outbreaks of resistance against wholesale adoption of Western models of modernity. Some reached the form of organized political campaigns, culminating in certain phases of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). But most remained on the level of conceptual alternatives formulated by individual thinkers and debated by public intellectuals. These repeated debates reflect the problematic compatibility of two goals simultaneously pursued by Chinese nationalism. One is to increase China’s wealth and power to the level of the most advanced nations, which implies copying their institutions, practices and values. The other is to preserve China’s independence and historically formed identity, without which nationalism loses any meaning.

What kind of synthesis could reconcile these two goals? Chinese philosophers, writers, artists and politicians all tried to come up with answers, which have been extensively studied.1 But it has only recently been noticed how the search for a Chinese way penetrated even the most central, least contested area of modernity – science, an institution widely perceived in China as both completely foreign and completely positive.2

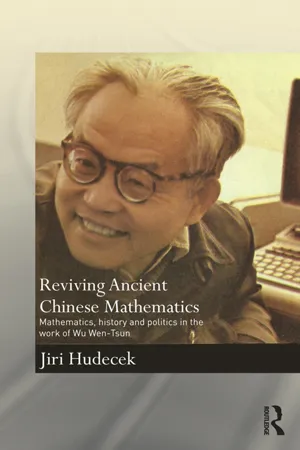

This book tells the story of an alternative Chinese mathematics, constructed or ‘revived’ not by a marginal mystic, but by one of China’s most productive and admired mathematicians, Wu Wen-Tsun (Wu Wenjun

– see the note on transcription at the end of this chapter). This revived Chinese mathematics also successfully rejuvenated Wu’s own career, paralyzed by the political turmoil and long isolation from international developments in post-1949 People’s Republic of China.

Wu Wen-Tsun (born 1919) entered Chinese mathematics shortly after the Anti-Japanese War (1937–45), just as mathematics had become firmly established in China as a vigorous research field. Wu drew upon the determined vision and international contacts of his first teacher Chern Shiing-Shen (1911–2004), and quickly demonstrated his talent in algebraic topology, a dynamic field after World War II.

Wu Wen-Tsun spent four years in France in the leading centres of his discipline and returned to China in 1951 as a coveted prize for the new Communist regime, which was trying to enlist patriotic scientists working abroad to help with the construction of a new China. But the disruption of Chinese science in the Great Leap Forward (1958–60) and especially the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) cut off Wu from his peers abroad and effectively ended his topological career. By the time he could resume research in the mid-1970s, a huge gap had built up between his knowledge and the state of the art in algebraic topology. So Wu started a new twin research programme instead – ‘mechanization of theorem-proving’ and, at the same time, a study of traditional Chinese mathematics. These efforts soon led to the Wu method of mechanization, which became recognized as a breakthrough by the international artificial intelligence community.

Wu Wen-Tsun situated his success within a nationalist framework of independent modernization, and at the turn of the millennium became a government-promoted celebrity for this reason. Against the standard ‘national hero’ story told about Wu, this book portrays his turn to the history of Chinese mathematics as a sophisticated negotiation between the two conflicting goals of Chinese nationalism mentioned above, provoked by obstacles to mainstream academic mathematics in Mao Zedong’s China.

Wu Wen-Tsun’s reorientation to an independent research path, presented as a development of traditional Chinese mathematics, was an act of symbolic significance both for Chinese nativism and for the advocates of science and modernity. His life and career have been used to defend these positions, which makes it both challenging and worthwhile to critically re-examine the historical record. Wu Wen-Tsun’s biographies published in China have generally avoided this task.3 Before saying more about the approach of this book, let me sketch the contexts in which Wu Wen-Tsun has been discussed.

‘You fight your way and I fight my way’

On 19 February 2001, the Chinese President Jiang Zemin awarded Wu Wen-Tsun the Highest National Science and Technology Award. The awards were established to promote Chinese ‘independent innovation’ (

zizhu chuangxin ),

4 and the theme was also stressed in Wu Wen-Tsun’s profile in the press release of the

New China agency:

In the late 1970s, against the background of great development of computer technology, he carried forward (

jicheng ) and developed the tradition of Chinese ancient mathematics (algorithmic thought), and turned to the research of mechanical proofs of geometric theorems. This completely changed the discipline: it was a pioneering work within the international automatic reasoning community. It is called the ‘Wu method’, and has had great influence internationally.

(Xinhua News Agency 2001a)

Wu Wen-Tsun claimed that his understanding of Chinese traditional mathematics enabled him to achieve a breakthrough in mechanical theorem-proving. This was so, Wu believed, because he approached the problem of automated proofs from a different angle than standard modern mathematics, inspired by traditional Chinese mathematics. He was able to succeed where others before him had failed, because he did not blindly follow established models from abroad.

This attitude was in line with the famous Maoist slogan of seeking ‘independence and self-reliance, regeneration through our own efforts’ (

duli zizhu, zi li gengsheng ). This was retained by the Communist Party of China (CPC) as part of the ‘living soul of Mao Zedong Thought’ after the Cultural Revolution.

5But Wu more often chose another Maoist slogan to sum up his rejection of a ‘universal’ model:

[During the Cultural Revolution] I read Mao Zedong’s

Selected Works from cover to cover. I started to side with Mao Zedong’s view. You fight your way, I fight my way, the enemy advances, I retreat, the enemy retreats, I pursue. I think it is the same with mathematics. The enemy in mathematics is nature (

ziranjie ).

(Wu Wen-Tsun, interview with the author, Beijing, 10 July 2010)

Wu described his scientific work in terms of warfare, since engagement in some kind of ‘struggle’ was the only legitimate activity in Maoist China. The words ‘You fight your way, I fight my way’ (

Ni da ni de, wo da wo de ) describe Mao’s flexible combination of guerrilla tactics and regular warfare, which he employed in the many years of the Civil and Anti-Japanese Wars.

6 Mao’s injunction also stresses strategic and innovative thinking, necessary in the backward conditions of developing China, as captured by Wu’s allusion to the famous ‘16-word rhyme’: ‘The enemy advances, we retreat; the enemy camps, we harass; the enemy tires, we attack; the enemy retreats, we pursue.’

7 For Wu, Mao’s definition of ‘fighting my way’ meant remaining the active party in conflict, always forcing ‘my’ terms on the enemy, withdrawing from engagements not to ‘my’ advantage.

The ability to remain active has been Wu Wen-Tsun’s chief concern since his return to China in 1951. He knew that he remained dependent on developments in world mathematics, to which he had only limited and intermittent access. He thus sought a perspective that would enable him to ‘fight with mathematical nature’ independently, using locally available resources. To his delight, he found this perspective through his study of traditional Chinese mathematics.

Chinese intellectuals have often debated these questions: Did China produce anything similar to modern science? Did Chinese intellectual heritage lack essential components of modern scientific method, such as logic or willingness to experiment? On the other hand, did it also include unique features which had contributed to ‘Western’ science or would do so in future? The last point was often taken up by those disappointed with modern civilization and fearful

of problems generated by purely ‘Western’ science.

8 Problems of this sort have often been subsumed under the so-called ‘Needham question’ (

Li Yuese nanti ), which became especially attractive for Chinese historians and philosophers of science after the end of the Cultural Revolution.

9The Needham question was the central concern of Joseph Needham’s monumental project Science and Civilisation in China, and was initially formulated quite narrowly:

How could it have been that the weakness of China in theory and geometrical systematization did not prevent the emergence of technological discoveries and inventions often far in advance (…) of contemporary Europe (…)? What were the inhibiting factors in Chinese civilization which prevented a rise of modern science in Asia analogous to that which took place in Europe from the 16th century onwards (…)?

(Needham 1954: 3–4)

It is important to note that the question had a negative aspect (China’s failure to generate modern science), but also a positive, affirmative part (China’s successful application of natural knowledge throughout the pre-modern period), which made it attractive for various types of Chinese modernizing patriots (Amelung 2003: 251).

Many Chinese scholars have focused on the negative aspect of the Needham question, searching for the causes of the backwardness of Chinese science in the early modern period, or sometimes on the inner ‘deficiencies’ of traditional Chinese science and technology (Fan Dainian 1997), which implied the unsuitability of this traditional heritage for the development of modern science. This attitude preva...