eBook - ePub

Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850

Christopher John Murray, Christopher John Murray

This is a test

- 1,336 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850

Christopher John Murray, Christopher John Murray

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

In 850 analytical articles, this two-volume set explores the developments that influenced the profound changes in thought and sensibility during the second half of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century. The Encyclopedia provides readers with a clear, detailed, and accurate reference source on the literature, thought, music, and art of the period, demonstrating the rich interplay of international influences and cross-currents at work; and to explore the many issues raised by the very concepts of Romantic and Romanticism.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850 est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850 par Christopher John Murray, Christopher John Murray en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Geschichte et Historischer Bezug. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

A

Abildgaard, Nicolai Abraham 1743–1809

Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard occupies a prominent place in the history of Danish art at the time of transition from the neoclassicist era to the Romantic era. A competent linguist, well-read and acquainted with the doctrine of neoclassicism, Abildgaard intended to establish a Danish equivalent to the grand style in history painting, as advocated in England by his contemporary James Barry. Furthermore, Abildgaard was an exponent of the aesthetics of the sublime, inspired by and thoroughly familiar with the works of Edmund Burke, Johann Gottfried Herder, and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. His subjects were found not only among the ancient Roman and Greek writers, but also in the works of William Shakespeare and Ossian, and he was among the first artists to deal with themes from Norse mythology and ancient Danish history, thereby paving the way for a Danish “national” iconography. Abildgaard expressed his talents in all areas of art, working as a painter, an architect, and a designer of interiors, furniture, and monumental sculpture. While occupying the positions of official court painter, and professor and director of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, Abildgaard expressed himself as a pre-Romantic revolutionary artist. According to Patrick Kragelund, the Danish scholar whose studies of Abildgaard’s work are the most thorough to date, the artist’s subjects reflect a constant development of his attitude toward important contemporary events, and his choice of subject matter may be perceived as one continuous world vision.

In 1764, ten years after the establishment of the Danish Academy, Abildgaard was admitted as a student. He was awarded the academy’s traveling scholarship in 1771, which lead to him finishing his studies with a stay in Rome from 1772 to 1777. While in Rome, he moved within a circle of artist friends, including Johan Tobias Sergel, the Swedish sculptor, and the Swiss-born artist Henry Fuseli; and apart from his study of classical sculpture, Abildgaard’s main areas of interest were the work of Annibale Carracci, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Giulio Romano. Yet he was fascinated also by the aesthetics of Sturm und Drang, which attracted much attention from artists in 1770s Rome. His principal work from this period is a remarkable depiction of Philoctetes (1774–75; Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen). Inspired by German philosopher Lessing’s treatise Laocoon (1766), Abildgaard presents the wounded Philoctetes, who clearly conveys his suffering not only by means of his facial expression and tearful eyes, but also through his entire body, twisted in pain. Abildgaard’s interpretation of this subject constituted a break with Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s notion of serenity, which is supposedly characteristic of truly classical Greek art. Likewise, it contrasted sharply with Barry’s version of this theme in a painting executed for the Accademia Clementina in Bologna in 1770. Abildgaard’s Philoctetes has been conceived as a manifesto of art, reflecting pre-Romantic ideals in the art of painting. At this point, the presentation of ideal, heroic subjects is replaced by the description of individual frames of mind.

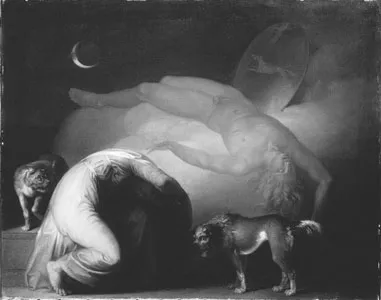

During his stay in Rome, Abildgaard was further introduced to other literary worlds, as found in the works of the three “original” geniuses: Homer, Ossian, and William Shakespeare. Inspired by Fuseli’s great enthusiasm for Shakespeare, Abildgaard decided to illustrate the same set of tragedies as chosen by the Swiss artist, in particular works such as Hamlet, Richard III, and Macbeth, which contain supernatural events, ghosts, and omens, and he worked on dreamy scenes with a distinctly Gothic atmosphere, for example, Richard III Waking from His Nightmare (1787), Richard III Threatened in His Dreams by the Ghosts of His Victims (1780s), and Hamlet and His Mother Seeing His Father’s Ghost (1770s?). However, the first scene from Hamlet treated by Abildgaard, Hamlet Visiting the Queen of Scotland (1776), had not been borrowed from Shakespeare: it was found in the bard’s Danish source of inspiration, the medieval historian Saxo Grammaticus, whose principal work, Gesta Danorum (1185–1222), was sent to Abildgaard in Rome. For some time, subjects from Greek and Roman antiquity were thus replaced with Nordic characters, with the artist aiming to evoke a grim and brutal past through his use of imaginative modification of clothing, props, and highly emotional figures. Abildgaard’s appreciation of the ossianic poems was almost certainly a result of his associations with British artists in Rome, and he appears to be one of the first artists outside of Great Britain to have illustrated the work of the Celtic bard (the veracity of which was eventually disputed). His interest extended to the acquisition of several annotated editions of James Macpherson’s poems of ossian, in which Abildgaard had marked scenes suitable for artistic treatment. Time and again, Abildgaard returned to this circle of themes, choosing to depict somber, tragic scenes from the heroic poems Fingal and Temora, such as his Cathmor by the Corpse of Fillan, Fillan’s Ghost Appears before Fingal, Cathmor and Sulmalla, and Fingal Gives His Weapons to Ossian (all c. 1790), in sepia drawings as well as paintings. In spite of his use of Gothic props, Abildgaard viewed the heroes of Norse mythology from a classical perspective. His masterpiece from this period is the eponymous, small painting of the blind Ossian (c. 1785; Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen), a tremendously passionate portrayal of the bard as wild and primitive: a solitary figure, alone with his harp, singing into a snow-clad and windswept, wooded landscape.

Upon his return to Copenhagen in 1777, Abildgaard was commissioned to execute a series of paintings with subjects from the national history of Denmark, or, more specifically, the history of the Danish royal dynasty. This commission, painted for the royal palace of Christiansborg between 1778 and 1791, gave the artist an opportunity to devise a formula for modern history painting. He decided that the series should be a glorification of the ideals of the Enlightenment: education, instruction, and knowledge, expressed in both allegorical and quasi-realistic scenes. This picture poem on the history of Denmark, which was to become Abildgaard’s most outstanding work, suffered a tragic fate: only three out of twenty-five original paintings survived a fire in 1794, although a number of oil sketches do remain.

With censorship in Denmark having been abolished in 1770, Abildgaard contributed to open public debate through allegories and social satire in different media and forms. As a prorevolutionary artist, he took a keen interest in the political and social conflicts of his time—for example, in 1788 as the originator and designer of draft plans for a monument to commemorate the abolition of serfdom in Denmark. The monument was executed as a cooperative piece by three sculptors after Abildgaard’s design and, under his direction, was erected in 1797 outside one of the Copenhagen town gates; here it enjoys a unique status, having been built by the citizens of the capital to commemorate the emancipation of the peasants. On a 1792 medal, struck in remembrance of the abolition of slavery in the Danish colonies, Abildgaard uses classic imagery in his reference to the recently declared rights of man. in place of the king is a profile portrait of the black slave; on the reverse, a classic depiction of a winged nemesis. Contemporaneously, Abildgaard refers in another work to the cult of the noble savage, in a 1795 painting that forms part of a series of interior decorations in the royal palace of Amalienborg, Copenhagen. Here, in a suppraporte, he represented Dance Scene from Tahiti (1794), a South Sea motif inspired by an illustration in Captain James Cook’s Voyage to the Pacific Ocean (1785). This motif has been introduced as representing the fifth continent, a subtle supplement to the current iconography linked to allegories on the four continents. Illustrations by the atheist Abildgaard for the classic Danish utopian novel The Travels of Niels Klim (1789), by Ludvig Holberg, constitute a bitter attack on the church. His illustrations for the Collected Works (1780) of the Danish poet Johannes Ewald caused much sensation and indignation at the time. This was due to the quite shameless approach taken by the artist in praising the naked human body and the “natural” relationship between man and woman in the Garden of Eden. Danish censorship was reintroduced in 1791. This was also the year in which Abildgaard was dismissed as court painter and director of the Royal Academy, and subsequently he undertook architectural and pictorial adornment of buildings such as the Levetzau Mansion at Amalienborg (for the royal family) and a citizen’s house in Ny- torv Square, Copenhagen. The latter was adorned with paintings of subjects from voltaire’s Roman tragedy Le Triumvirat. For his own home at the Academy (Charlottenborg, Copenhagen), Abildgaard executed four large paintings of scenes from Terence’s comedy The Woman of Andros (1801–4; Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen); as architectural pieces, these are most significant as visions of the Athens of antiquity.

The Spirit of Culmin Appears to his Mother, From The Songs of Ossian. Reprinted Courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library.

Although Abildgaard was a professor at the Royal Academy for several years from 1778 until his death in 1809, he has no direct successors in the history of Danish art. Among his pupils we find Asmus Jacob Carstens (pupil, 1776–81), Caspar David Friedrich (pupil, 1794–98), and Philipp Otto Runge (pupil 1799–1801). All three were strongly influenced by their meeting with Abildgaard and his distinct views, with regard to the philosophical and poetic dimensions of pictorial art, as well as pertaining to the freedom of the artist as a “citizen of the republic of artists”; here, according to Abildgaard, the artist is his own master.

METTE BLIGAARD

Biography

Born in Copenhagen on September 11, 1743, the son of the painter Sören Abildegaard. Apprenticed as a decorative painter to J. E. Mandelberg. Entered the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen around 1764. Won the academy’s silver and gold medals 1765, 1766, and 1767. Awarded traveling scholarship to Rome, 1771. Lived and studied in Rome, associating with artists Johan Tobias Sergel and Henry Fuseli, among others, 1772–77. Returned to Copenhagen via Paris, 1777. Professor at the Royal Academy, Copenhagen, from 1778; director, 1789–91 and 1801–9. Commissioned to decorate Schloss Chris- tiansborg, 1780–91, and later the Amalienborg Palace. Member of the Berlin Royal Academy, 1788. Engaged in design of interiors, furniture, and architecture from 1790s on. Member of the Accademia in Florence, 1808. Died in Sorgenfri (Frederiksdal?), near Copenhagen, June 4, 1809.

Bibliography

Kragelund, Patrick. Abildgaard around 1800: His Tragedy and Comedy. Analecta Romana Instituti Danici 16. Rome: L’Erma, 1987. 137–183.

Kragelund, Patrick. Abildgaard, Homer and the Dawn of the Millennium. Analecta Romana Instituti Danici 17–18. Rome: L’Erma, 1989. 181–224.

Kragelund, Patrick. Abildgaard, kunstneren mellem oprørerne I–II. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum, 1999.

Kragelund, Patrick. “Nicolai Abildgaard and the Wounded Philoctetes,” in Art in Rome in the Eighteenth Century. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Art Museum, 2000.

Sass, Else Kai. Lykkens tempel. Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1986.

Swane, Leo. Abildgaard. Arkitektur og Dekoration. Copenhagen: Kunstakademiets Arkitektskole, 1926.

Adolphe 1816

Like his unfinished novel Cécile and his Journaux intimes (diaries), with which its genesis is inextricably linked, Henri- Benjamin Constant de Rebecque’s Adolphe is rooted in the emotional entanglement of the author’s divided affections for two women, Charlotte von Hardenberg and Anne-Louise-Germaine de Staël during the second half of the year 1806, when, still living and working on treatises on politics and religion in the entourage of the latter, he fell passionately in love with the former. Though Constant and Hardenberg were to be (secretly) married in June 1808 and his final break with Madame de Staël would occur in 1811, he delayed publishing his novel, which was probably completed by 1810 if not before, until 1816— mainly, it is thought, to avoid offending Staël. Upon its publication the novel was naturally read as a roman à clef by a public familiar with its author’s relationships, leading him to the dubious assertion in the preface to the second edition (1816) that “none of the characters drawn in Adolphe has any link with any individual.”

Constant, who was closely associated with Staël and the Cop- pet group (Coppet was the name of Staël’s estate in Switzerland, where her salon met), was a supporter of the incipient Romantic movement, and Adolphe is often considered to be a masterpiece of the Romantic or pre-Romantic novel. His preoccupation with the uniqueness of the individual; with the complexity and fluidity of human emotions; with the importance of nuances and the emptiness of general laws and principles; with the transitoriness of life and the insufficiency of language to express the subtleties of human feelings and thought are major themes of his works— and particularly of Adolphe—that link him to the Romantic movement. Indeed, the main protagonist and narrator of Adolphe is often held to be a characteristic Romantic hero in terms of his introspection, alienation, and sensibility. Critics have established links with other significant texts of the early Romantic canon: Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Nouvelle Héloïse (The New Elo- ise, 1761), Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Die Leiden desjungen Werthers (The Sorrows of Young Werther, 1774), and François- Auguste-René, Vicomte de Chateaubriand’s René ...

Table des matières

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- List of Entries

- List of Entries by Subject

- List of Entries by National Developments

- Notes on Contributors

- Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850

Normes de citation pour Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850

APA 6 Citation

Murray, C. J. (2013). Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850 (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1672543/encyclopedia-of-the-romantic-era-17601850-pdf (Original work published 2013)

Chicago Citation

Murray, Christopher John. (2013) 2013. Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1672543/encyclopedia-of-the-romantic-era-17601850-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Murray, C. J. (2013) Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1672543/encyclopedia-of-the-romantic-era-17601850-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Murray, Christopher John. Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2013. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.