eBook - ePub

EU-Russian Border Security

Challenges, (Mis)Perceptions and Responses

Serghei Golunov

This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

EU-Russian Border Security

Challenges, (Mis)Perceptions and Responses

Serghei Golunov

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

The land border between Russia and the European Union is one of the longest land borders in the world, with very considerable trade flowing across the border in both directions. This book examines the nature of the EU-Russia border, and the issues connected with its management. It describes the territories and the societies on each side of the border, discusses the challenges which confront border management, including migration and criminal activities, and explores how people on both sides perceive each other and perceive threats and security issues. It concludes by assessing achievements to date in managing the border and by assessing continuing unresolved challenges.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que EU-Russian Border Security est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à EU-Russian Border Security par Serghei Golunov en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Social Sciences et Ethnic Studies. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

1 Introduction

What is border security?

Border security is a topical and fashionable concept that is frequently used in a context when a state counteracts threats such as terrorism, drug trafficking, and human trafficking. However, the employment of this term for describing empirical issues and determining border management agendas goes far ahead of its theoretization; this can be explained by at least two reasons.

First of all, conceptual research on border security is not a fashionable trend in contemporary border studies, as its implicit state-centrism and stress on territorially fixed national borders contradict the current dominance of postmodernist, con- structivist, and critical trends. It can nevertheless be argued that border security studies does matter. Indeed, to ignore issues that, in harsh reality, need to be dealt with someway both by border policy-makers and border crossers would make research irrelevant to practice.

Second, the problematic and geographical limits of the border security agenda are still rather vague. Indeed, which border policy issues may be reasonably associated with the realm of security, and which ones should be withdrawn from it as routine problems? In order to separate border security from other kinds of security, should its focus be limited by the border itself and the relatively narrow adjacent territories (borderland zones, counties, sometimes provinces) that are affected by the relevant security regimes and arrangements?

It would be rather difficult in our case to advocate some rigid objectivist approach, as the assignment of some or other issues to the security agenda is largely subjective, and as modern practical approaches to solving these problems often go beyond strict territorial limits. Therefore, the approach to border security employed in this book is constructivist. More specifically, it is derived from the Copenhagen school’s securit- ization concept, the essence of which is that a problem is construed as a security issue (i.e. a problem requiring urgent and extraordinary solutions) by means of the securitization move, made by actors raising the issue. This move is addressed to an audience that can accept or not accept it (Buzan et al., 1998: 25–32). In this case I find it necessary to assume that the audience itself can be not only passive but also sometimes very active, encouraging or even compelling (e.g. from the perspective of losing political popularity) political actors to securitize a problem. Additionally, by the analogy with securitization, I introduce the concept of the ‘borderization’ of the security issue, which means construing such an issue as having its solution in border protection measures. Thus, in this case, the problem is constructed twice – first as a security issue, and then as something that should be solved within the framework of border policy.

My constructivism, however, is mild rather than radical. First, I assume that the desecuritized and deborderized state of the issue is not more ‘natural’ than the securit- ized and borderized one: so, deconstruction can be considered as a useful analytical tool, but not as a universally desirable practical option. Second, I presume that the securitization and borderization of a problem is facilitated by some objective factors (or ‘hard facts’), such as an increasing number of illegal immigrants and drug addicts, a decline in production as a result of smuggling in goods and so on. Therefore, in addition to the perceptions associated with the securitized boundary issues, illegal immigration and smuggling of various kinds will be the special focus of my study. From a geographical point of view, the problems to be qualified as border security issues may not necessarily be localized at the border or within borderland areas, but they should have a border as their reference axis anyway: for example, visa issues may be dealt with far inside a departure or a destination country, but such a decision is about allowing a person to cross a quite precise geographical boundary.

Finally, the consideration in this book of the border security agenda also includes the side-effects of border security measures. Strict border and customs controls often entail a reduction of cross-border mobility and huge queues, and trigger the growth of corruption and extortion in the border protection agencies. These side-effects may easily become no less of a problem than the very challenges that led to tough border security measures in the first place.

The EU–Russian border

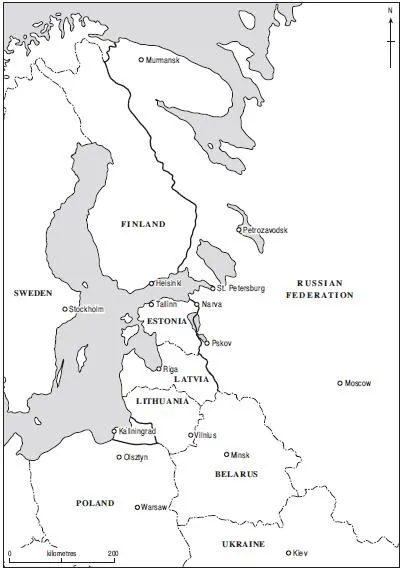

Russia currently has land borders with the following five European Union member states (from north to south): Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. It should be noted that while mainland Russia does not have borders with Lithuania and Poland, its exclave Kaliningrad province does.

There is some difficulty in determining the spatio-temporal framework for the current research, which is caused by at least two circumstances. First, the border between the EU and Russia can be considered, on the one hand, as a common frontier of the European Union, and, on the other, as the composite of the borders that the aforementioned EU member states have with Russia. This raises the questions of when and to what extent the main emphasis should be put on the border in its entirety, and in which cases the emphasis should be on the heterogeneous character of the EU–Russian border. Second, it raises a problem in that this border has not been static over the last two decades: it did not appear in final form overnight, but gradually became more extended during the post-Soviet period.

In the first few years after the Soviet collapse, Russia did not share a border with EU member states at all: from 1995 to 2004, Russia’s only EU neighbour was Finland, and it is only since 1 May 2004 that this border has assumed its present size and shape, which are not expected to change, at least from a short-term perspective. In addition, it should be taken into account that the quality of the border has changed gradually, as Russia’s neighbours that were members of the EU did not immediately join the Schengen zone: Finland joined in March 2001, while the Baltic states andPoland joined in December 2007.

Map 1.1 The EU–Russian border

Resolving the dilemma of homogeneous versus heterogeneous representation of the EU–Russian border(s) depends on a context determined mainly by the balance between national policies and the supranational EU’s norms and powers, which regulate border security issues, as well as the role to be played by the European Union as the whole or its member states bordering Russia in construing the border security agenda. Particularly in the contexts of visa policy and the fight against irregular migration, the EU–Russian border is more homogeneous than heterogeneous, since differences in national visa policies seem to be less significant than the influence of the common framework, defined by the Schengen acquis. On the other hand, the fights against smuggling in consumer goods, queues at the border and malpractices by border guards and customs officers tend to be more determined by the peculiarities of national border policies than by the common policy of the European Union. At the same time, in these and in other cases, the choice of a representation should take into account specific situations and the particularities of their perceptions by significant actors. Inasmuch as this book, as its title implies, focuses mainly on the homogeneous representation of the EU–Russian border, it is quite understandable that it considers the problems of border security primarily in light of their impact on cross-border mobility and the corresponding visa policies.

With regard to the changeability of the EU–Russian border, it would hardly be expedient to consider each national boundary of Russia with its north-western neighbours starting only from the time when these countries joined the European Union. Such an approach could undermine the conceptual integrity of the analysis and the synchronization of processes occurring in different parts of the contemporary EU–Russian borderland. The currently relevant border security agenda has not been shaped solely in the period since some countries adjacent to Russia became EU members. It has instead been shaped in the period after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the opening of the ‘Iron Curtain’ and the weakening of law enforcement and immigration control in the post-Soviet space, combined with the severe deterioration of the socio-economic conditions in the USSR’s successor states, created conditions for the dramatic growth of irregular migration, transnational organized criminal activities, and various kinds of smuggling operations.

In order to trace the EU–Russian border security agenda from the beginning, the situation at Russia’s borders with the current EU member states will be considered from the early 1990s onwards. Of course, it will not be forgotten that the considered boundaries did not become those of the EU and of the Schengen zone immediately: this is why such terms as ‘Russia’s borders with the current EU countries’, ‘Russia’s north-western border’, and so on will be used when appropriate. Alongside this, the author will take into account the significant and relevant changes in the corresponding border security agendas after Finland, the Baltic countries, and Poland joined the EU.

Existing works on the topic

There are virtually no large studies covering the entire EU–Russian border and which, at the same time, are devoted to border security. This can be explained both by the fact that such studies, covering five national borders at once, are very time-consuming to undertake and require analysis of large amounts of empirical data, and also by the already mentioned and somewhat marginal position of research on border security within contemporary border studies.

Yet a lot of research is relevant to the topic of this book. In particular, it is popular to conceptualize the EU–Russian border as an exclusion line that keeps Russia outside of European integration (Browning 2003; Cronberg 2002; Haukkala 2010; Joenniemi 2000; Medvedev 2008; Prozorov 2006). In this light one can mention studies that emphasize the widespread, alarmist and negative perceptions of the ‘Other’ at both sides of the border, fuelling this exclusion (Bukhar in 2007b; Forsberg 2006; Moisio 1998; Morozov 2003; Muizˇnieks 2008; Paasi 1999; Pursiainen 1999; Rytövuori- Apunen 2008b; Sergunin 2004). Accordingly, in cases where the authors of such studies suggest measures for improving the situation, they focus mainly on changing the discourse in relations between Russia and the EU or its individual member countries, rather than on empirical solutions.

‘Physical’ obstacles for cross-border movement between Russia and current EU member countries have also been considered in many studies (Holtom 2003; Karabeshkin et al. 2004), and in some of these both material and virtual barriers have been examined (Berg and Ehin 2004; Cronberg 2006; Kolossov and Borodulina 2007). Among the barriers that have a strong material dimension, the issues related to the visa regime that the EU maintains towards Russian citizens has probably attracted the closest scholarly attention (Petrova 2010; Salminen and Moshes 2009; Wasilewska 2009). By contrast, the side-effects of strict border security measures, such as huge queues of vehicles and the malpractices of border and customs officers, are examined rarely (Fairlie and Sergounin 2001; Pihlak 2008), and overwhelmingly no more than in passing.

The number of studies that pay attention to issues of cross-border crime, such as various kinds of smuggling and organized illegal immigration, is relatively small, and besides this their empirical information is largely outdated (Galeotti 1995; Ganzle and Kungla 2002; Hakola 2000; Holtom, 2003; Ivakhoniuk 2005; Vares 1999). Meanwhile, the insufficient attention paid to these problems in contemporary research on the EU–Russian border weakens the argumentation of those scholars and politicians who are calling to make border controls and the visa policy of the EU towards Russia less (or, on the contrary, more) exclusionist in comparison to the current state of affairs. Thus, issues of cross-border crime deserve more attention in current EU–Russian border studies than they actually receive.

One more group of works is devoted to problems of border and visa manage- ment of current EU member countries adjacent to Russia (Clemmesen 1998; Gromadzki and Wasilewska 2008; Niemenkari 2002; Petrova 2010; Pihlak 2008). Unfortunately, the perspective of practitioners, who ultimately determine border security policies, is typically not taken into account by researchers focusing on mainstream inclusion/exclusion issues relevant to the EU–Russian border. As the lack of attention to this perspective can easily make such studies one-sided and biased, the problems of border and visa management also merit more thorough scrutiny than has been the case in the recent past.

Thus, there is a need for studies covering the entire EU–Russian border and con- ceptualizing the relevant security issues, taking into account the perspectives of both the practitioners who shape and carry out border security policy and border crossers who face the barriers created by this policy. The author hopes that his research can serve as one of the initial steps in this direction.

Conceptual approach

Within mainstream border studies, empirical problems generally matter only to the extent that they are important as illustrations for various theories. More specifically, within the framework of modern theories, priority is given to the role of borders during globalization, in constructing the identities of Self and Other, as instruments of power and exclusion, and as a subject of border-related discourses.

Such a situation creates a risk that theoretical research, especially that dedicated to hard and heavily protected borders, may find itself irrelevant to practice. First of all, being carried away by border-related discourses that are not carefully juxtaposed to reality, a researcher risks making his findings dependent on the rhetoric of those public figures who claim to be supporters of certain ideas in word, but do not pay much attention to those ideas in deed. Second, mainstream border studies theories largely do not encourage a researcher to collect empirical information about the specific problems experienced by border crossers and to propose solutions that could solve these problems in the foreseeable future. Third, in such theories, it is often considered good style to criticize the ‘outdated’ and ‘unjust’ approaches of national governments towards border protection; however, it is rarely considered necessary to offer a viable and realistic alternative to these approaches. Meanwhile, practitioners (including those making decisions in the area of border policy) often have to deal with so-called ‘wicked problems’, which, among other things, have no clear right or wrong solutions and cannot be fully understood before these solutions are worked out and tested, but, on the other hand, each solution option involves unintended consequences and new ‘wicked problems’ (Conclin 2005: 5, 14–15). In other words, decision-makers in the field of border security often have to choose not between good and bad, but simply between more or less bad options. This gives decision-makers a good reason not to pay attention to destructive criticism, which often derives from post-positivist (especially critical) border studies scholars.

In order to bridge the gap between theory and practice, an approach combining the ideas of pragmatism and dialogism has been put at the core of this book’s conceptual background. The pragmatist maxim, or, as some call it, the ‘pragmatist razor’, which proclaims that the essence of the idea is in the sum of its practical consequences (Peirce 1992: 132), actually impels a researcher to give priority to the most practically relevant ideas and issues, relegating to the background less practically relevant ones. The application of dialogism is aimed at facilitating dialogue to be held primarily between the ‘gatekeepers’ (politicians and officials responsible for border security policies, and also a section of the public that supports strict border protection measures) and non- criminal border crossers (labour immigrants, tourists, cargo carriers, shuttle traders, etc.) on improving border policy and achieving a better balance between the interests of these and sometimes other groups of actors (e.g. borderlanders). The role of researchers may be in providing assistance to the parties in developing the agenda of such a dialogue, as well as in the diagnosis of its current state (‘Whose voices are heard poorly?’, ‘Does any party suppress others?’, etc.) and in making propositions on the further development of its organizational forms.

Structure of the book

In the current chapter the pivotal characteristics of the book’s subject are clarified: the contents and the applicability of the limits of the concepts of ‘border security’ and the ‘EU–Russian border’ are specified. In addition, I briefly characterize the pragmatist- dialogical approach employed for focusing the research on practical problems and in arranging efficient dialogue between ‘gatekeepers’ and border crossers.

The second chapter examines in detail the existing theoretical approaches that can be used for the conceptualization of border security, and also several empirical cases in which different strategic approaches to border security policy have been employed. While in the theoretical section of the chapter the main watershed lies between positivist and post-positivist theories, in the section devoted to practical approaches this lies between prioritizing border security and cross-border cooperation. In the final section the pragmatist-dialogical approach, already mentioned in the introduction, is considered in detail.

The third chapter is focused on examining, on the one hand, key ‘material’ char- acteristics (length of the border, landscape, socio-economic indices in adjacent border- land areas, intensity of cross-border flows) and, on the other, the widespread images, perceptions, and representations of the EU–Russian border and also of the coterminous Other behind it. This chapter serves as the empirical background of the research, taking into account the fact that the mentioned material and virtual factors to a large extent shape the EU–Russian border security agenda and the options chosen for managing the relevant issues.

The fourth chapter deals with issues of migration through the EU–Russian border, including the characteristics of legal and illegal migration flows, as well as the problems of dialogue between ...

Table des matières

- Front Cover

- EU–Russian Border Security

- Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations and acronyms

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Border security: towards conceptualization

- 3 EU–Russian border(land): characteristics and representations

- 4 Immigration as a security issue

- 5 Smuggling and grey trade

- 6 Border protection: strategies, achievements, and side-effects

- 7 Conclusions

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Normes de citation pour EU-Russian Border Security

APA 6 Citation

Golunov, S. (2012). EU-Russian Border Security (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1685399/eurussian-border-security-challenges-misperceptions-and-responses-pdf (Original work published 2012)

Chicago Citation

Golunov, Serghei. (2012) 2012. EU-Russian Border Security. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1685399/eurussian-border-security-challenges-misperceptions-and-responses-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Golunov, S. (2012) EU-Russian Border Security. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1685399/eurussian-border-security-challenges-misperceptions-and-responses-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Golunov, Serghei. EU-Russian Border Security. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2012. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.