1 Introduction

Drivers of change in upland environments: concepts, threats and opportunities

Aletta Bonn, Tim Allott, Klaus Hubacek and Jon Stewart

Introduction

Uplands are globally a crucial source of ecosystem services, such as provision of food and fibre, water supply, climate regulation, maintenance of biodiversity, as well as providing opportunities for recreation, inspiration and cultural heritage (see Box 1.1). They are often of exceptional natural beauty, centres of species distinctiveness and richness, and historically have been extensively managed for food production owing to difficult terrain and thus low productivity. This is reflected in the fact that most upland regions in Europe, as well as globally, receive national and international conservation designations. In addition, the uplands provide livelihoods and homes for local residents, but often in marginal economies with associated social, economic and demographic problems. Owing to their natural beauty, uplands often provide opportunities for recreational and educational activities for visitors, contributing major direct or indirect income streams for local communities and regions. An example of the impact of reduced tourism on rural economies has most dramatically been demonstrated by the effects of access closures during the foot-and-mouth disease outbreak in Britain in 2001 (see Curry, this volume).

However, upland environments face threats and sometimes competing challenges from pressures such as climate change, atmospheric pollution deposition, policy and funding direction, land management and anthropogenic disturbance. These in turn drive related changes in fire risk, increases in erosion and water colour, degradation of habitats, loss of biodiversity and recreational value, as well as significant demographic shifts and changes in the economy of these marginal areas. In the past fifty years the uplands have seen increasing pressures to meet growing demands for food, timber and opportunities for recreation. These changes have helped to improve the livelihood of some, but at the same time have weakened nature’s ability to deliver other key ecosystems services (MA, 2005). Less tangible but sometimes extremely important benefits to society have tended to take second place to the more immediate and sometimes short-term benefits. Considering the added challenges posed by climate change, these issues are thrown into sharper focus. In fact, uplands have been identified as particularly vulnerable with respect to climate change (IPCC, 2007), and profound changes are likely to both environments and societies in upland regions and beyond.

Box 1.1. Upland ecosystem services

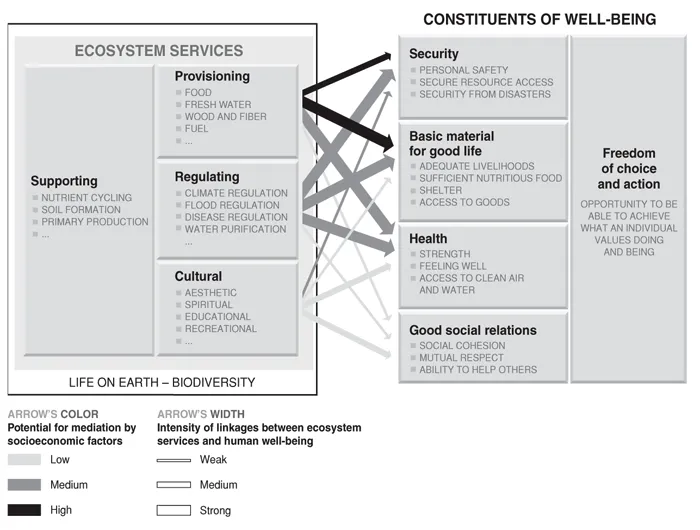

Environmental, socio-economic and political drivers all impact directly or indirectly on the ability of ecosystems to provide important ecosystem services. The concept of ecosystem services has been developed to aid the understanding of the human use and management of natural resources. Ecosystem services are the processes by which the environment produces or regulates resources utilised by humans such as clean air, water, food and materials that are indispensable to our health and well-being. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA, 2005) identifies four major categories of ecosystem services that directly affect human well-being (Figure 1.1). For the uplands this means:

Figure 1.1 Linkages between ecosystem services and human well-being (reproduced by kind permission of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment: MA, 2005).

- Provisioning services deliver important ecosystem products. Upland ecosystem products include food (livestock, game, crops), hay for livestock, timber for building material, fuel such as peat or wood, and minerals used in industry and construction. Most notably, upland catchments provide over 70 per cent of fresh water in Britain. Uplands can also provide a source for hydro-electricity or wind power.

- Regulating services in the uplands include air-quality regulation through atmospheric deposition and cooling. UK uplands actively contribute to climate regulation. As 50–60 per cent of UK soil carbon is stored in peatlands, most of this in uplands, the maintenance, enhancement through further carbon sequestration, or degradation of these stores can affect the local climate and contribute to global climate change. Further examples of regulating services include erosion and wildfire regulation as well as water regulation, affecting water quality and quantity.

- Cultural services include non-material benefits people obtain from uplands, such as enjoyment of landscape aesthetics, biodiversity and cultural heritage. Uplands are considered some of the most natural ecosystems and typically have low population densities, therefore providing invaluable opportunities for recreation, spiritual enrichment and education. It is not surprising that they are a major tourist destination.

- Supporting services are those services that are necessary for the production of all other ecosystem services. Uplands and their habitats and species play a major role in nutrient and water cycling, as well as in soil formation.

People vitally depend on these services. Healthy upland ecosystems can normally maintain a sustainable flow of these services, even when affected by change and disturbance (for a detailed list, see Table 25.1, this volume). The full benefits people gain from these services are difficult to measure, as are the costs when these are lost. However, by unsustainable management we may risk losing these upland services for present and future generations.

The aim of this book is therefore to identify and discuss some key directions and drivers of change in upland environments, how ecosystem services are affected by them and can become drivers in their own rights. It provides insights into how future management and conservation options might address the challenge of sustaining ecosystem services.

The book provides up-to-date scientific background information and lays out pressing land-management questions, the answers to which are needed to address policy-related issues. Our goal is to showcase examples of high-quality research from a wide range of disciplines reflecting the need to understand the complex environmental, social and economic interactions that characterise the uplands. We aim thus to provide relevant information to help inform discussions between organisations, scientists and practitioners relating to sustainable management of uplands. We hope this book appeals to students in environmental and social sciences, researchers, environmental practitioners, land managers, policy-makers, and others with an interest in the functioning and management of fragile upland environments and economic marginal areas. Most of the papers draw heavily on UK experience but are of wider applicability to uplands around the world, especially those experiencing relatively intensive pressures. Many of the themes have applications beyond upland regions.

Definition of uplands

It takes a brave person to make a definitive claim as to what constitutes the uplands. There is some discussion on definitions in relation to the English uplands in The Upland Management Handbook (English Nature, 2001). As stated there, the distinction between uplands and lowlands is blurred. It will also tend to vary depending on the factors being considered. Taking a habitat lead, uplands can be considered as areas above the upper limits of enclosed farmland (Ratcliffe and Thompson, 1988). However, there is a very strong link between the open land above the limit of enclosure and the more intensively managed farmland. As a boundary for the uplands we use the term Less Favoured Areas (LFA; see Figure 4.2, Condliffe, this volume) developed by the European Union. Although originally introduced primarily as a socio-economic designation, LFA does tie in well with upland habitats. LFA describes an area where farming becomes marginal and less profitable because of natural handicaps (such as harsh climate, short crop season and low soil fertility), or that is mountainous or hilly, as defined by its altitude and slope, or that is remote. Uplands can therefore be defined by climatic conditions that affect plant growth, and altitudinal demarcations can vary in different regions (Fielding and Haworth, 1999).

Drivers of change

As drivers of change are multi-faceted and multi-dimensional, the book has a strong interdisciplinary scope. It is important to identify the nature of the drivers and distinguish between their source, their duration, their impact and their interactions as well as their direct or indirect nature.

Direct drivers influence ecosystem processes explicitly, and can usually be recorded and measured with differing degrees of reliability. They can be natural short-term drivers, such as extreme weather events leading to floods or erosion, or natural long-term drivers, such as changes in climate influencing blanket bog formation. Important anthropogenic drivers include land use and management leading to desired or unintentional habitat and ecosystem service change, overexploitation (e.g. excessive grazing), fragmentation, degradation (e.g. drainage or intensive burning) and disturbance (e.g. wildfire and visitors). All of these drivers are local and internal to the ecosystem affected, and can be addressed by a change in management. External short-term and long-term anthropogenic drivers include pollution through atmospheric deposition or runoff, as well as acceleration of natural levels of climate change. Furthermore, some natural drivers such as invasion by alien species or pest species are also often triggered by human activity (e.g. intentionally or unintentionally introduced species becoming naturalised). Direct drivers are relatively well recognised and documented, although their effects and interactions are not always clearly understood.

In contrast, indirect drivers operate by altering the level or rate of change of one or more direct drivers and include demographic, socio-political, economic, technological and cultural factors. For example, the recent change of US and EU policies with regard to biofuels or weather-induced reductions in crop outputs have implications for lowland and subsequently upland agriculture patterns with implications for the continued provision of upland ecosystem services. Such links between indirect drivers and their effects on upland environments are not always clear and are often subject to time delays. They are often external to the affected ecosystem, and complex interactions with a multitude of other indirect and direct drivers make them less easy to measure or to predict. Important indirect drivers of change include changes in population (e.g. size and age structure of farming communities), changes in policies and legislation, economic incentives (e.g. Common Agricultural Policy Pillars 1 and 2), and shifts in socio-cultural values (e.g. leisure patterns). As awareness grows of the important links between how uplands are managed and their role in providing ecosystem services such as carbon storage, water provision and downstream water-flows, these services are starting to drive change through policy, legislation and economic incentives.

Book structure

The first section addresses the broad external and long-term drivers over which local practitioners have little influence. These include natural processes (Evans) as well as anthropogenic drivers such as climate change and air pollution (Caporn and Emmett). The policy drivers that tend to steer land management in the short and longer term are outlined (Condliffe).

The second section considers a variety of upland ecosystem services that can be both driven by and drive change. It addresses past, present and anticipated future processes, and identifies options for responses to these different drivers of change. Major ecosystem services provided by the uplands include carbon storage and flux (Worrall and Evans), water yield and flood protection (Holden), provision of freshwater (Allott) and terrestrial habitats (Crowle and McCormack; Yallop, Clutterbuck and Thacker). Land management and changes in land use, with grazing and burning as the dominating forms of land use, are discussed with regard to their direct effects on habitat characteristics and farm economy (Gardner, Waterhouse and Critchley). Moorland wildlife services are covered as exemplified by birds (Pearce-Higgins, Grant, Beale, Buchanan and Sim), mammals (Yalden), and game and shooting interests (Sotherton, May, Ewald, Fletcher and Newborn). The effect of past management and cultural heritage for the upland landscapes today is discussed (Bevan), and the importance of recreation in uplands for human well-being and rural economies reviewed (Curry).

The third section of the book considers changing upland institutional, social and economic systems, and how these might influence the choices we make for ecosystem service provision from the uplands. This section provides informed visions and advice for future management of public goods. First, an overarching analysis of the changing economic circumstances of the uplands is provided (Hubacek, Dehnen-Schmutz, Qasim and Termansen). Next, potential future trends and approaches to farming—arguably the most important direct influence on upland ecosystems—are explored in relation to commons and farm integrity (Burton, Schwarz, Brown, Convery and Mansfield) and at the landscape scale (Hanley and Colombo). Developing the landscape-scale approach, the value of landscape character as a framework for policy is discussed (Swanwick). Landscape is very much concerned with the relationship of people and place, and the next chapter investigates how visions for multiple benefits of land use can be achieved through scenario-building and participatory approaches involving all relevant stakeholders (Arblaster, Reed, Fraser and Potter). Following, these ideas are developed in discussing whether sustainable governance of public goods can be achieved by public participation and how different approaches vary in success (Connelly and Richardson). The next chapter takes a particular aspect of public engagement and addresses the influence of social barriers and class on the enjoyment of these landscapes (Suckall, Fraser and Quinn). Another aspect of the role of the public is considered in looking at the threats from wildfires (McMorrow, Lindley, Aylen, Cavan, Albertson and Boys). The authors model spatial and temporal risks to develop mitigation strategies, such as informed recreation planning and fire prevention measures. In areas of past inappropriate management or damaging wildfires, the health of upland ecosystems and habitats can be severely negatively impacted and prime ecosystem functioning can be lost. In such areas restoration may help to reestablish ecosystem functions and services (Anderson, Buckler and Walker). Given the role of conservation in helping restore ecosystem health, it is fitting that the last chapter of this section looks at upland conservation. Informed by clear visions and strategies to deliver, conservation has to meet new and sometimes not so new challenges such as climate ...